Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

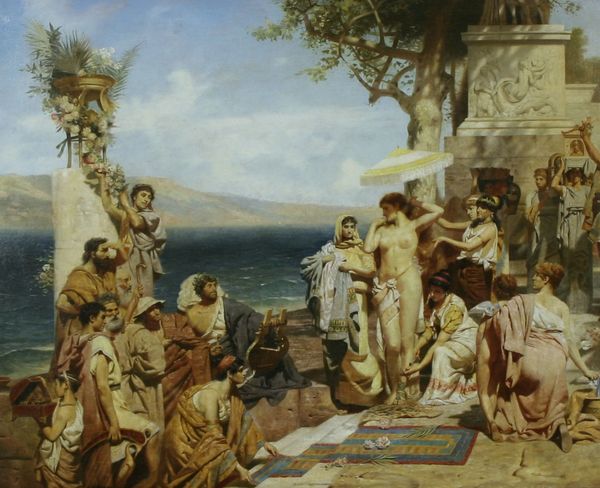

Editor: So this is "The Judgement of Paris" by Henryk Siemiradzki, painted in 1892. It's an oil painting depicting a scene from Greek mythology. It feels very staged, almost like a tableau vivant. What strikes you most about it? Curator: Immediately, I think about the complex legacy of Neoclassicism. Siemiradzki, though working in the late 19th century, is deeply entrenched in this tradition which consciously resurrected classical aesthetics. This revival, however, happened within a very specific social and political context, mostly among the dominant European and white elites. Do you think his vision of ancient Greece speaks to that, a kind of idealization linked to power? Editor: I think so, definitely. It feels romanticized. Were there alternative interpretations of Greek myths at the time? Curator: Absolutely. There were burgeoning artistic movements questioning these idealized visions. Realism and early Symbolism, for example, explored the darker, less palatable aspects of human existence, moving away from the grandiose narratives favored by academic art. How might viewing this painting through a feminist lens shift our understanding? Consider the objectification of the goddesses, and Paris's role as a male judge. Editor: I see your point. The goddesses are presented for male appraisal, which is kind of uncomfortable given the power dynamics implied. Does Siemiradzki engage at all with critiques of colonialism through his rendering of classicism? Curator: That's a compelling question, and one not often asked about Siemiradzki. The visual cues like architectural details suggest specific regions dominated by Empires throughout the 19th century. By replicating such environments, is he inadvertently legitimizing existing social hierarchies or expressing sympathy with people oppressed at that time? His intentions remain complex. Editor: It gives me a lot to think about—beyond just a pretty picture. I guess there’s more here to consider when looking at supposedly neutral historical painting, especially concerning power dynamics. Curator: Precisely. Art always reflects, either consciously or unconsciously, the society that produces it, inviting us to question whose perspectives are centered and whose are marginalized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.