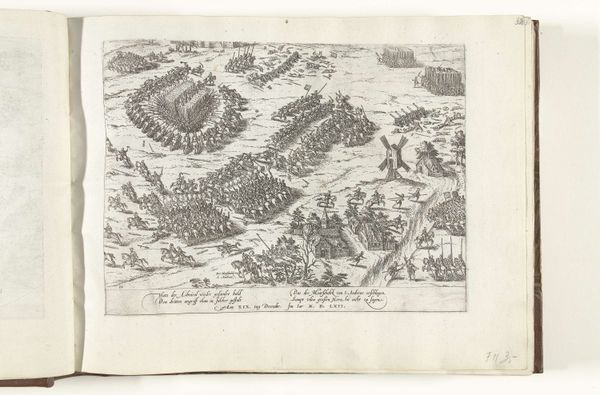

print, ink, engraving

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

mannerism

#

ink

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 376 mm, width 505 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

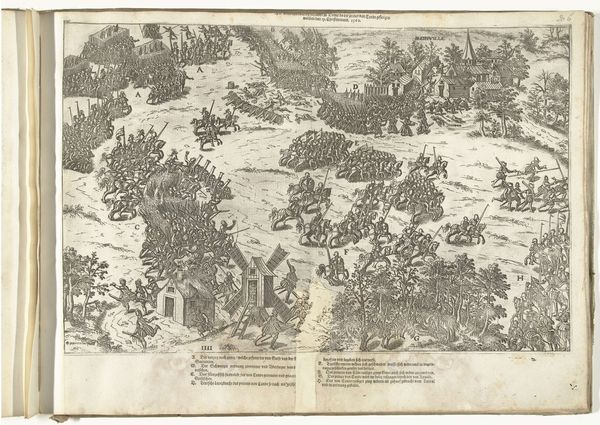

Curator: This densely packed print by Jean Perrissin depicts the Battle of Dreux, specifically the third encounter during the battle in 1562. It was rendered in 1570 using engraving and ink, a typical medium for disseminating such scenes at the time. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of chaos and overwhelm. The sheer number of figures, the frenetic lines—it really conveys the intensity of a battlefield, doesn't it? It feels almost abstract until you start picking out the details. Curator: That abstraction is interesting. While Perrissin aims to represent a specific historical event, he employs a Mannerist style, prioritizing visual complexity and stylized forms over strict realism. Notice how he uses lines to define forms and create a sense of depth? It is also clear to see how the lines add to the image's busy quality, which I believe adds another level to the art’s impressionability. Editor: Exactly. And it’s not just a formal choice. Showing the third encounter within a religious war like this also makes me wonder about the politics embedded within. Was it made to celebrate a victory, warn of the conflict's endlessness, or just a chronicle from a supposedly neutral point? Whose perspective are we given through the piece? Curator: That's crucial. The print needs to be viewed through the lens of the French Wars of Religion, specifically. As an engraver creating for a public audience, his choice to depict the battle this way carries certain weight. Engravings were reproducible; prints like this one disseminated information but also solidified certain narratives and perhaps bolstered collective memory in favor of a specific community. Editor: Right, art served a very direct, propaganda-type purpose for centuries. Plus, who was given access to this image, who was taught how to read its imagery, and what message did they receive. Was its message of reassurance through familiarity, like keeping a common story afloat by feeding new stylistic content to it? It is something to explore. Curator: Precisely. And think about the historical reception, this was displayed in places of learning and shared throughout families—creating impressions of an actual event. What does an image like this create when no photograph ever existed? This helps ground our understanding of the socio-political and institutional circumstances of the time. Thank you. Editor: Agreed. Thanks for unpacking it with me. It reminds us that even seemingly straightforward historical depictions are ripe with questions about power, memory, and visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.