drawing, paper, chalk, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

chalk

#

15_18th-century

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

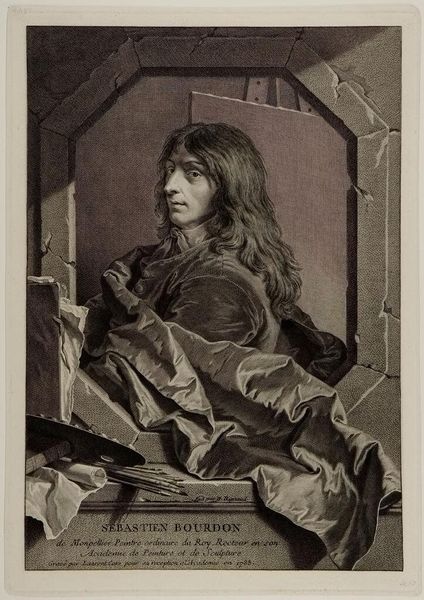

Curator: Let's discuss this compelling image, "Portrait of the Painter Sébastien Bourdon" rendered in chalk and charcoal on paper by Hyacinthe Rigaud, likely completed between 1730 and 1733. It currently resides here at the Städel Museum. Editor: It strikes me with a melancholic beauty. The blue paper imbues a serene, almost somber quality to the piece. Notice how the drape of the fabric contrasts against the harsh lines of the window frame? Curator: Precisely. The structural contrast there is significant. Observe the artist's expert handling of line and light. The sharp, architectural lines of the window geometrically oppose the sinuous folds of Bourdon's clothing, achieving dynamic tension through formal opposition. Semiotically, that jagged frame—broken in two places—hints at something fractured, both physically and metaphorically. Editor: I see it slightly differently. I find it incredibly interesting how Rigaud chose to portray Bourdon amidst the tools of his trade, specifically, next to his art easel, brushes and palette. In some traditions, depictions like this can act as symbolic affirmations of his identity and professional legitimacy. That is, this is the painter in his milieu, but through rendering the frame incomplete, Rigaud alludes to perhaps, unrealized dreams, or current, creative blocks. Curator: A potent reading, drawing from symbols! From a purely compositional perspective, consider the contrast between the crisp details of the face and the soft, almost blurred treatment of the fabric. This directs the viewer’s attention to the face. Editor: Yes, the artist's choice to emphasize the face brings to mind not only Baroque portraiture but also something inherently and perpetually human; this timeless capture that invites empathetic consideration, don't you think? Rigaud is reminding us that at our essence, despite craft and profession, is human identity. Curator: I am captivated by Rigaud's capacity to weave layers of both structural complexities and iconic profundity into this very powerful image. Editor: Absolutely. Thank you for illuminating these nuanced connections, allowing a fuller appreciation of this portrait’s symbolic depths and emotional breadth.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Hyacinthe Rigaud's portrait drawing of the painter Sébastien Bourdon (1616-1671) is a brilliant example of early eighteenth-century French portrait art. During the late seventeenth century Rigaud had risen to become the leading portraitist of the French court and aristocratic society with a painting style which combined an elegant appearance with sensuous colouristic effects. His famous state portrait of Louis XIV (today in the Louvre in Paris) set the standard against which the other courts of absolutist monarchs measured themselves. Although highly esteemed, relatively few of Rigaud's portrait drawings have survived - making the group of four excellent sheets owned by the Städel Museum all the more important. They were formerly part of the collection of Johann Friedrich Städel and document his interest both in eighteenth-century French drawings and in portraits. The outstanding work in this group is this portrait of the artist. Bourdon, who had died in 1671, was one of the founding members of the Académie Française and also its rector for a while.Rigaud portrayed him after an oil painting that he personally owned and presented to the Académie in 1735. The drawing, executed exclusively in black and white chalk on blue paper, shows the subject through a picturesque stone window frame. Bourdon seems to be about to turn his attention to the easel discernible in the background, having turned round briefly to look at the viewer. The voluminous drapery enveloping him creates an inward movement which draws the viewer's gaze into the picture. The painter's tools - palette, paintbrush, portfolio, book and sheets of paper - are arranged on a stone balustrade in front of the window. Rigaud's chalk technique differentiates skilfully between the textures of the thick dark hair, the velvet jacket, the silky sheen of the drapery and the stone frame. In spite of this precision the drawing as a whole looks masterful and generous. In 1733, the copper engraver Laurent Cars (1699-1771) created an engraving of this work, a brilliant masterpiece with which he was accepted into the Académie. Rigaud's drawing must have been completed only a short while previously. Whether he was already thinking of having the drawing made into a print when he executed it is not certain. The multiple references to the Académie nonetheless suggest that this was the case.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.