Copyright: Public domain

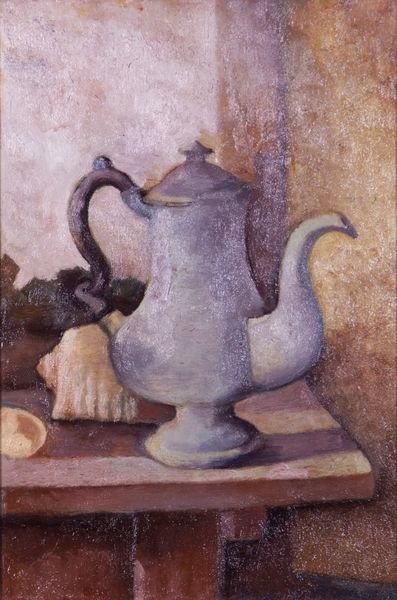

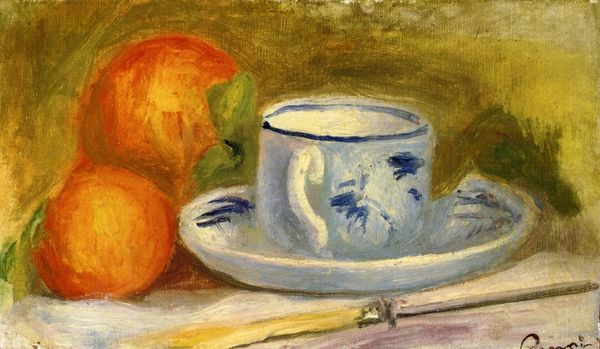

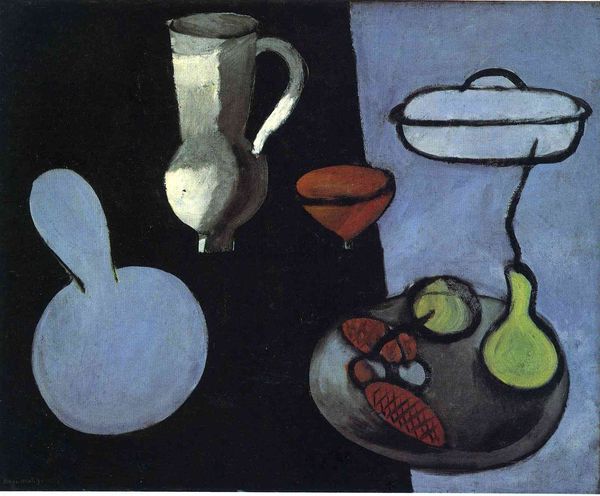

Editor: This is Henri Rousseau's "Still life with teapot and fruit" from 1910. There's something both comforting and unsettling about this arrangement of ordinary objects. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, I see it as a reflection of the societal shifts occurring at the turn of the century. Rousseau, though self-taught, was deeply connected to the artistic pulse of his time. The flattened perspective and seemingly naive rendering can be viewed as a rejection of academic tradition and a quiet subversion of bourgeois expectations. How do you think this ties into discussions around class and access to art education at the time? Editor: That's fascinating, I hadn't thought about it that way. It's almost like he's democratizing the still life, bringing it down to earth. Curator: Exactly! Consider the teapot, for instance. It's not ornate or ostentatious, it’s functional and accessible. By placing this commonplace object at the center of the composition, is Rousseau subtly questioning what is worthy of artistic representation? And how does this relate to Post-Impressionism's move away from purely representational art? Editor: So, it's not just a pretty picture, but a commentary on class and artistic conventions. It makes me think about who gets to decide what art *is*, and how those decisions are often political. Curator: Precisely! It prompts us to consider the social forces at play. This piece is not just a still life. It’s a quiet revolution on canvas, challenging our preconceptions about art and society. What have you learned? Editor: I’ve definitely gained a deeper appreciation for the layers of meaning embedded in seemingly simple paintings, and I'll certainly approach other artworks with more of a historical and social awareness going forward. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.