Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

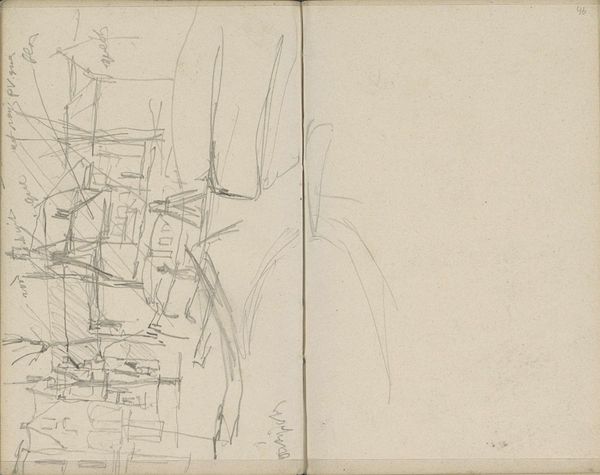

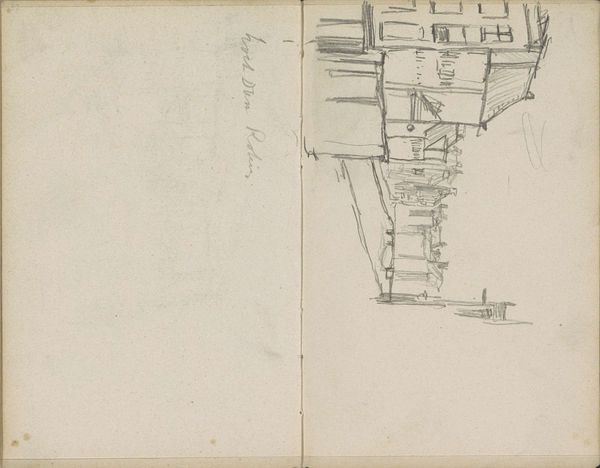

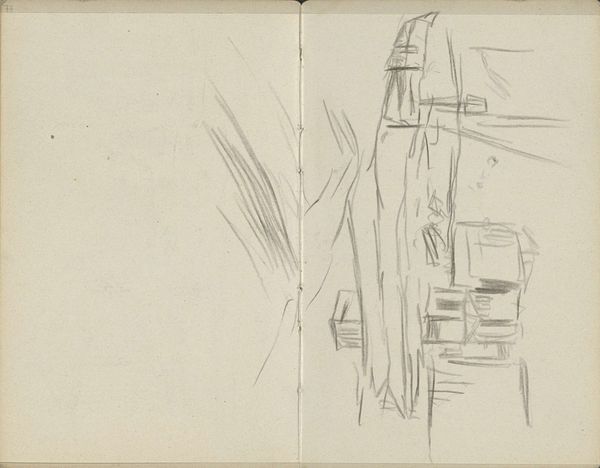

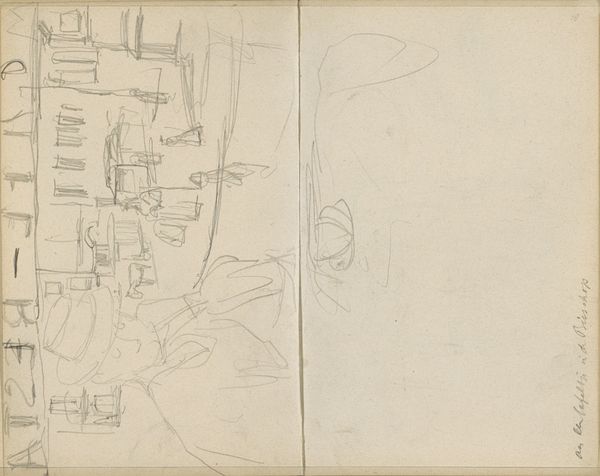

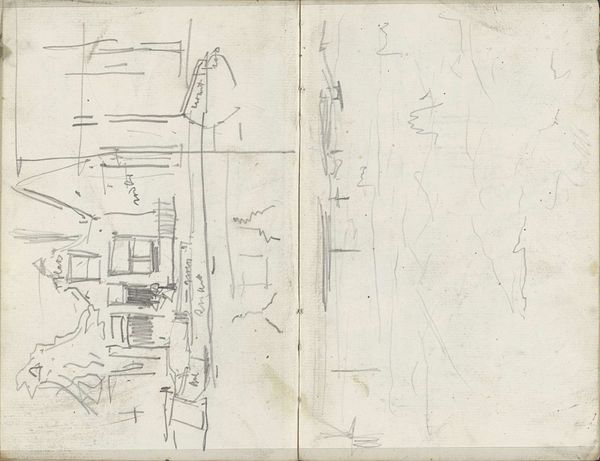

Editor: This is "Studie," a pencil and ink drawing from around 1909 by George Hendrik Breitner, currently at the Rijksmuseum. Looking at this page from Breitner’s sketchbook, I’m struck by its unfinished quality; you can almost feel the artist's hand moving across the page. What do you see here? Curator: I see the remnants of labor. These aren't precious compositions intended for a gallery. They're raw materials, evidence of Breitner working through ideas. Notice the quick, repetitive strokes; they speak to the industrial pace of modern life that impressionists like Breitner were grappling with. Editor: Industrial pace? That's interesting! I wouldn't have necessarily made that connection just looking at it. How so? Curator: Think about the materials: cheap paper, readily available pencils and ink. These were mass-produced items, accessible to a wider range of artists. The sketchbook itself suggests a kind of artistic assembly line – ideas captured and processed, one after another. It's almost a form of artistic labor, a proto-factory churning out visual concepts. Editor: So you're saying that even the materials themselves contribute to this idea of industry and labor? It’s like he’s documenting his thought process, in real time. Curator: Exactly. Breitner wasn't just depicting the world; he was engaging with the very processes of production and consumption that shaped it, through his own artistic practice. What might those marks have to say about a modernizing world in the 20th century? Editor: That's a really fascinating way to look at it! I was focused on the aesthetic aspect, but understanding the social context and materials gives it a whole new layer of meaning. Curator: Precisely. It moves us beyond simple aesthetic appreciation into a critical engagement with the artwork’s material and historical conditions of creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.