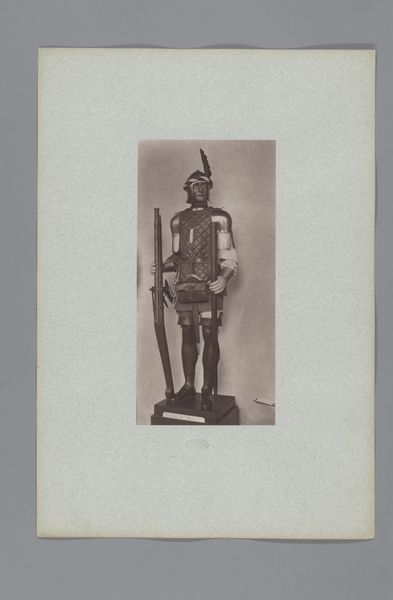

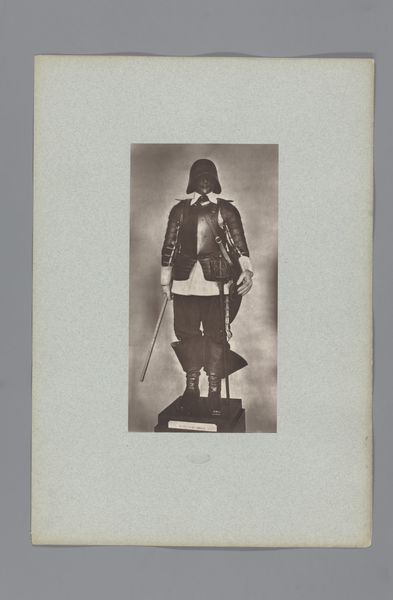

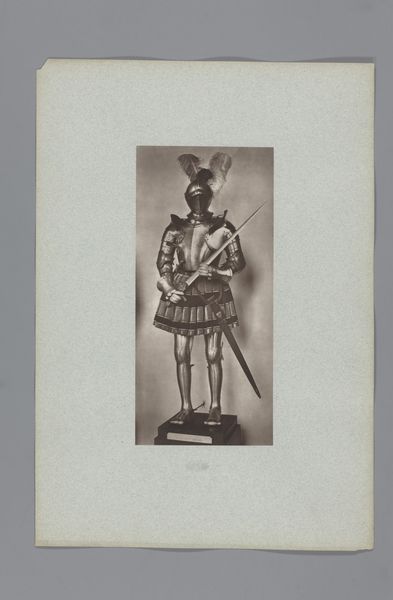

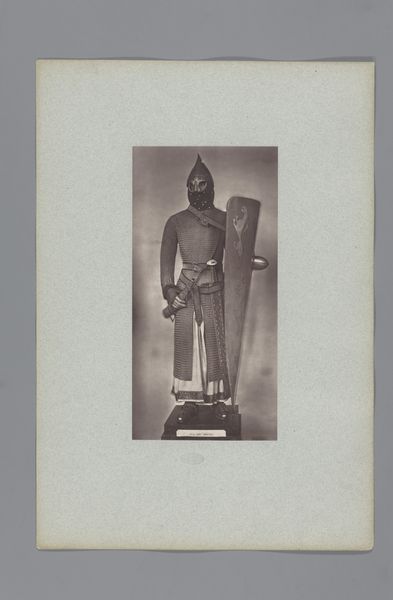

15de-eeuws harnas met zwaard en boog uit het leger van Karel VII van Frankrijk, uit de collectie van het Musée d'Artillerie in Parijs before 1882

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

photography

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The work before us is a photographic print dating back to before 1882, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Its rather lengthy title tells us it's a "15th-century armor with sword and bow from the army of Charles VII of France, from the collection of the Musée d'Artillerie in Paris." Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its melancholic stillness. There's an almost ghostly presence to this lone suit of armor, removed from its context, a solitary figure caught in time. It’s as if the weight of history, the countless battles and sociopolitical conflicts this armor witnessed, has been compressed into this image. Curator: Indeed, and that's partly due to how photographs gained popularity during that era, intertwining art and documentation in representing national narratives and ideals. This photograph reflects the French interest in solidifying and remembering their historical heroes. This representation, and similar displays, shape our understanding of power and identity tied to Charles VII. Editor: I wonder about the intended audience, and what it means to put this historical figure’s representation on display. Doesn’t that reify these notions of power through what theorists like Foucault described as “docile bodies"? By visually re-presenting this armor, it can promote nationalist sentiments through a visual lens, connecting viewers to certain ideals of medieval Europe and war, even promoting or reinforcing such behaviors as strong, patriotic or brave. Curator: You make a compelling point about docile bodies. The photograph aestheticizes the implements of war, which in turn gives a nostalgic patina to the harsh realities. It evokes romanticized notions, such as the nobility and even chivalry associated with medieval warfare. But for soldiers it’s not chivalry; it’s about national interests or, as you suggest, certain political inclinations, and sometimes about maintaining power and suppressing social dissent. Editor: Absolutely, it glosses over the bloodshed and systemic oppression that these wars perpetuated. When art isolates, elevates, and romanticizes objects linked to conflict, it subtly sanitizes historical injustices and becomes part of the cycle. To fully grasp this photograph, we need to dismantle these mythologies by questioning not just what the armor represents, but whose perspectives are privileged and suppressed by this artistic approach. Curator: Precisely. It urges us to acknowledge the biases embedded within the art historical cannon and confront art’s potential as a tool of propaganda, and an endorsement of hegemonic powers. Editor: I think that unpacking historical and social connotations through this critical lens provides insights not just into our past but offers essential context in confronting the complex structures in contemporary power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.