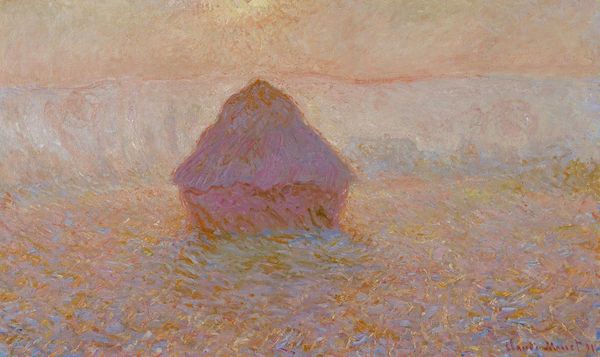

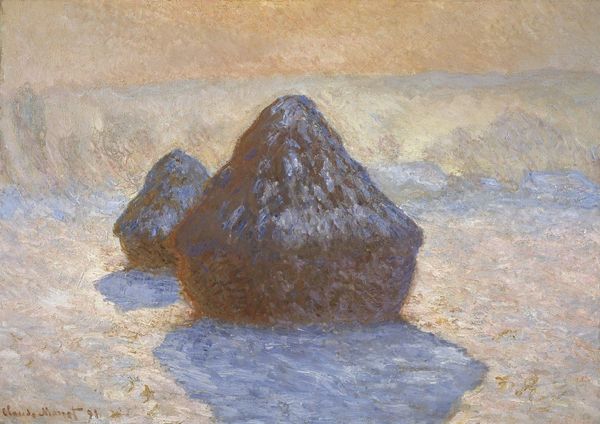

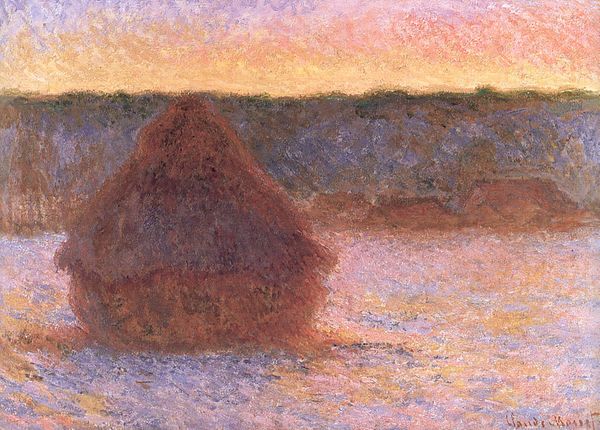

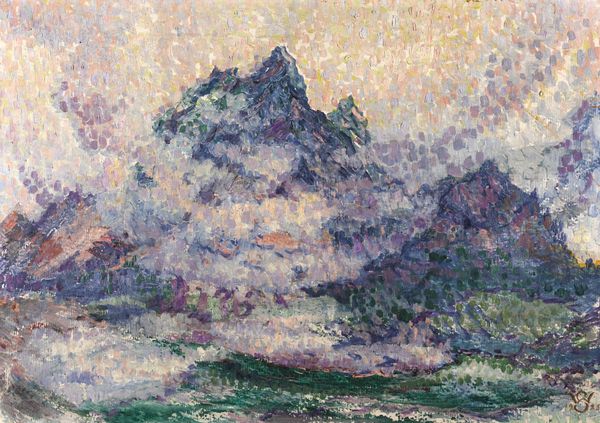

Dimensions: 65 x 100 cm

Copyright: Public domain

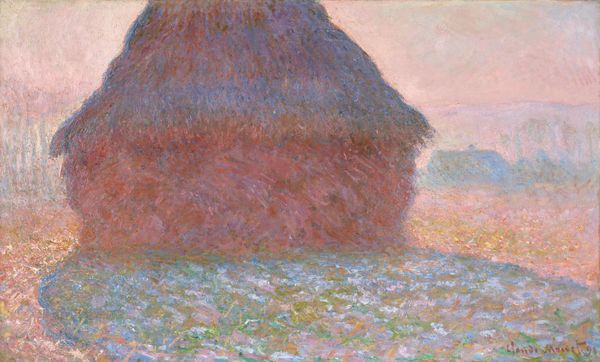

Curator: Standing before us is Claude Monet's "Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect)," painted in 1891. It currently resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's strikingly muted, almost monochrome. The palette leans heavily into blues and pinks, casting a tranquil yet melancholic atmosphere over the scene. The brushstrokes, particularly on the haystacks themselves, give a sense of texture that's almost tangible. Curator: Monet's series of "Haystacks" paintings are fascinating examples of plein-air painting. They reflect the radical politics of impressionism, in the sense of removing the studio from the artistic process, bringing artwork directly into the sphere of the public, the every day. Consider this: Monet rented a room specifically to capture these scenes at different times of day and under various weather conditions. It became almost an obsession. Editor: An obsession that translated into an acute awareness of the mutability of the landscape. The paintings aren’t merely records of haystacks, they are studies on the fleeting nature of light and how it fundamentally alters our perception. The socio-economic backdrop also begs consideration; such an agricultural subject would undoubtedly carry weight for those whose livelihoods depended on the land. Curator: Precisely. The impressionists were revolutionary in how they rendered the everyday and celebrated aspects of modernity. He uses the impasto technique, building up thick layers of oil paint. These rough brush strokes aren’t just about aesthetics, are they? It’s an experience for the viewer’s eye, recreating Monet's subjective experience. Editor: Yes, and one wonders about his intentional use of such thick applications, suggesting the heavy burden of those dependent on successful crops. Are those wheat stacks symbols of wealth, or perhaps monuments to backbreaking work, rendered even more isolating by winter's harsh touch? There is also an inherent issue of class involved. Monet was from the middle class, with resources and opportunities generally out of reach to the average agrarian worker, and those dynamics affect this artistic viewpoint. Curator: Interesting how an image so focused on the transient and atmospheric can carry so many layers of social meaning! Considering this landscape through Monet's radical impressionist lens, and then considering those same scenes of manual labor though the eyes of those dependent on their crop yield, is truly what these images are still useful for today. Editor: I agree. It is art that acts as a cultural mirror and lens to deepen not just how we understand artistic method, but life during the Third Republic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.