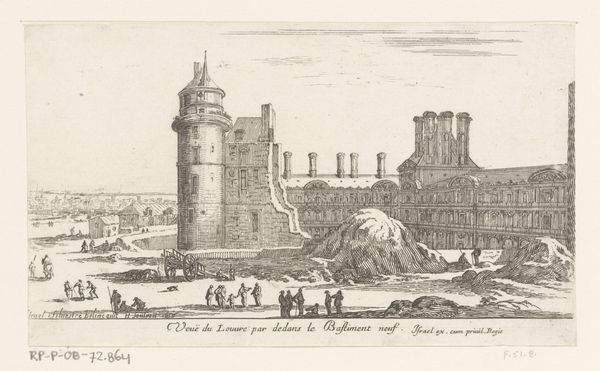

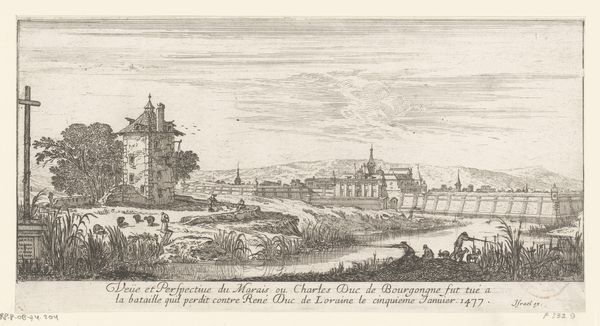

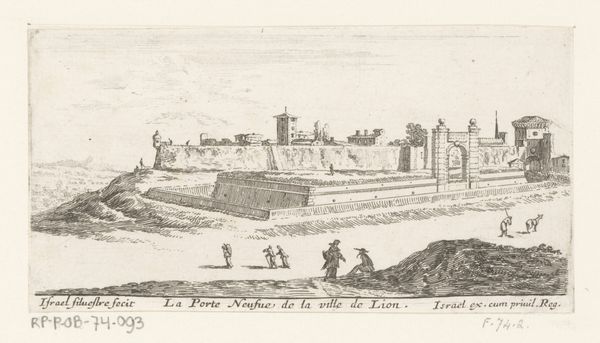

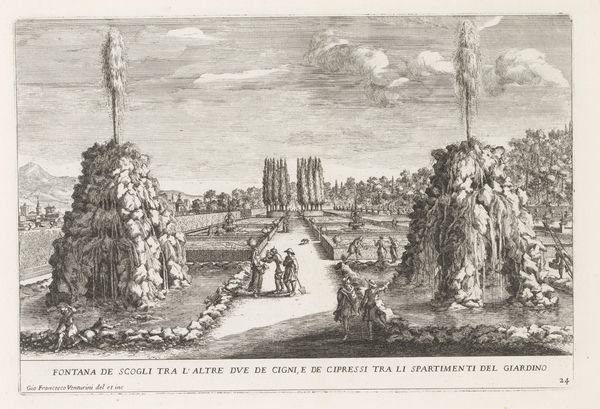

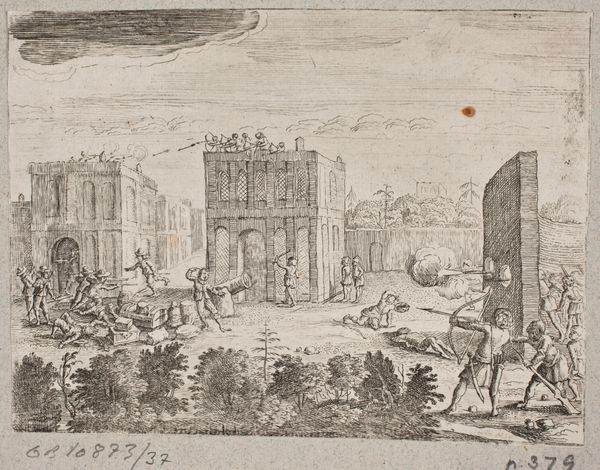

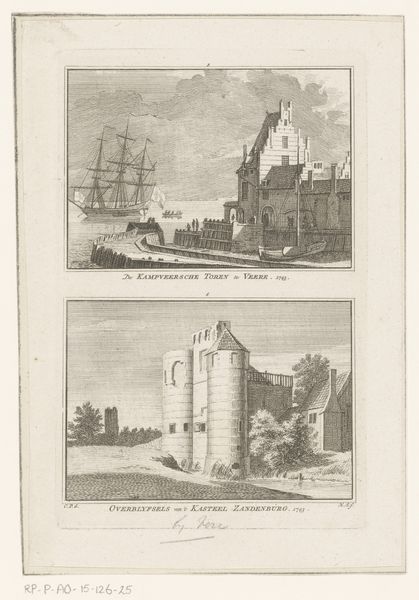

drawing, print, etching, ink, engraving, architecture

#

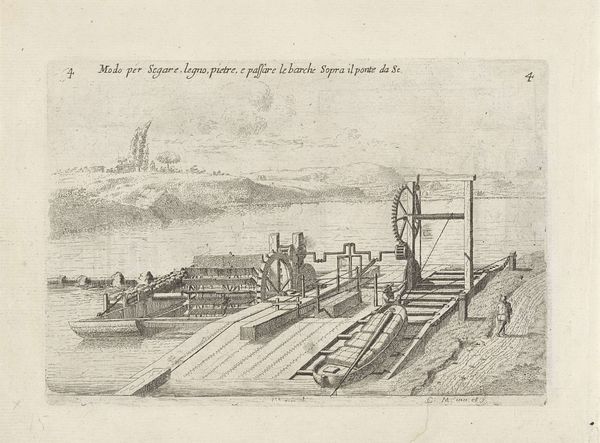

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

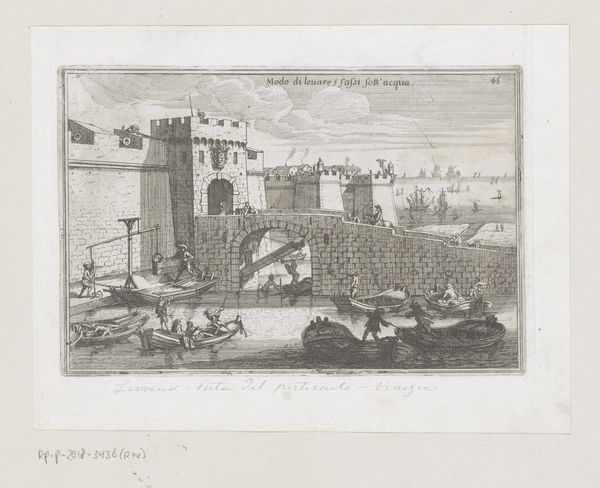

baroque

#

mechanical pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

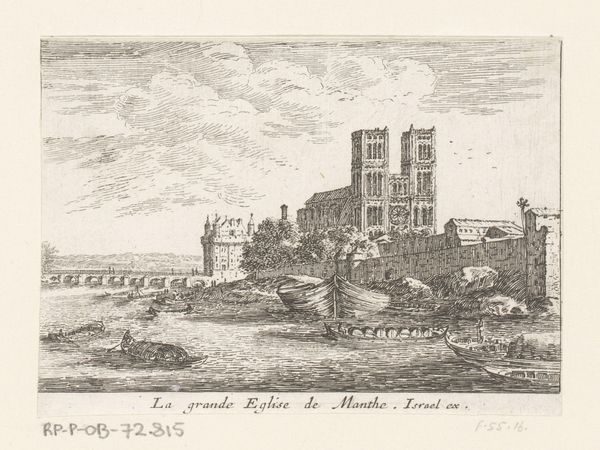

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Israel Silvestre’s "View of the Château de Vincennes," created sometime between 1631 and 1661 and housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, offers a captivating look at a site brimming with French history. It’s crafted using etching and engraving techniques, showcasing incredible detail. Editor: It’s almost unsettlingly neat, isn’t it? Everything feels so orderly, like a stage set rather than a real place. The fine lines create a crisp, almost sterile feeling, despite the activity depicted. Curator: Precisely! This depiction served a political purpose; these engravings were distributed amongst members of the French Aristocracy and members of the Royal Courts of Europe to bolster favor for Louis XIV through propaganda and city planning. Consider the period: France was centralizing power. Art became a tool to project authority and grandeur. Silvestre's strategic representation is important; it creates an imposing statement about control over territory. Editor: So the artistic creation is almost secondary to its role in solidifying power structures and distributing status? The very act of reproducing this image – the materials used, the techniques employed, etching as a democratic medium– were instrumental to expanding the monarchy’s political network. Curator: Absolutely. Note how he meticulously renders architectural elements but also includes anecdotal elements like passersby. Are these figures symbols of court life, reinforcing the chateau’s centrality as a place where power is circulated? The details aren’t just aesthetic, they reinforce social hierarchy, don't you think? The act of printing and circulating these engravings became performative tools. Editor: Indeed. It almost negates the craft—that is if one focuses solely on aesthetic concerns. If you consider how such pieces function, the printmaker is no longer just someone who translates a visual idea into material form. Silvestre’s prints create an understanding and relationship to space. This extends into the physical exchange and ownership of the prints themselves. Curator: Looking at Silvestre’s work, it reminds us of how urban landscapes are always intertwined with ideology and politics. It’s about so much more than pretty buildings and neat lines. Editor: Precisely, it encourages to see art as less of an end product and more a node in the construction of broader political narratives and material practices. It is about making and distributing propaganda.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.