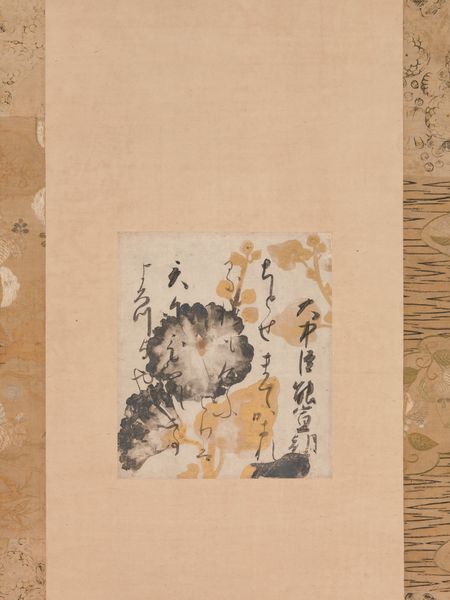

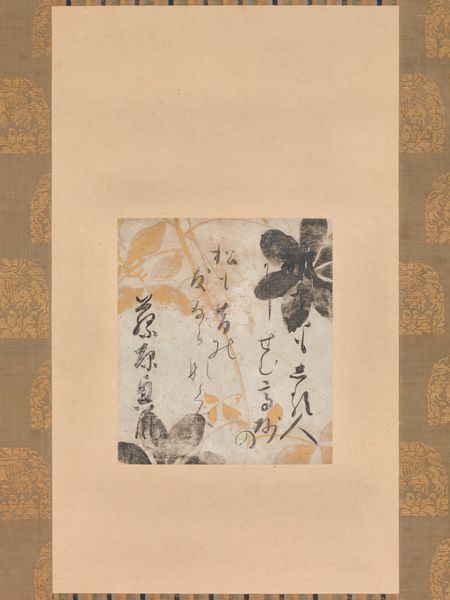

Dimensions: 15 1/16 × 22 3/4 in. (38.26 × 57.79 cm) (image)47 3/4 × 28 5/8 in. (121.29 × 72.71 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

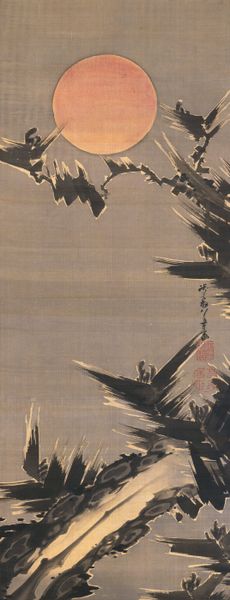

Kenkō Shōkei painted these wagtails with ink and color on silk during the Muromachi period. The wagtail, or "sekirei", often appears in Japanese art and literature as a symbol of fidelity and the joys of domestic life. Consider how birds, across cultures, have been seen as messengers between the earthly and spiritual realms. This motif recurs in ancient Greek art, where birds often accompany deities, and in medieval Christian iconography, symbolizing the soul's flight to heaven. Note how Shōkei's wagtails, perched serenely on a branch, echo similar depictions of birds in Song Dynasty paintings from China, embodying a sense of peace and harmony with nature. Such imagery taps into a collective longing for tranquility, a sentiment deeply embedded in the human psyche. The wagtail, a modest bird, becomes an emblem of profound emotions. These symbols persist, evolving yet retaining their primal power to stir our souls.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Kenkō Shōkei was both a Zen priest and a highly skilled ink painter who spent most of his career at the major Zen monastery Kenchōji in the city of Kamakura. Here he depicted a pair of wagtails on branches in strikingly contrasting poses. One stares down to the right as if aiming at some prey, while the other stands straight with a glance to the left. Shōkei painted his birds using a rapid brush technique called “boneless” (that is, without outlines), a method seen as particularly suitable for Zen themes. This combination of compositional device and technique suggests that these wagtails once flanked a third painting of a Zen deity or patriarch as part of a devotional triptych. Pictures of birds or flowers often served this purpose in Zen painting. But Shōkei’s original format seems to have been radically transformed by some later owner. Not only is the central painting missing but the vertical seams on each painting suggest that a previous owner cut up the original paintings to create two large horizontal compositions. The new format was less suitable for a Zen temple but fit the wide display alcove typical of grand residences. This type of conversion of a once sacred image to a secular one was not uncommon in Japan after the 1500s.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.