drawing, print, metal, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

metal

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

doodle art

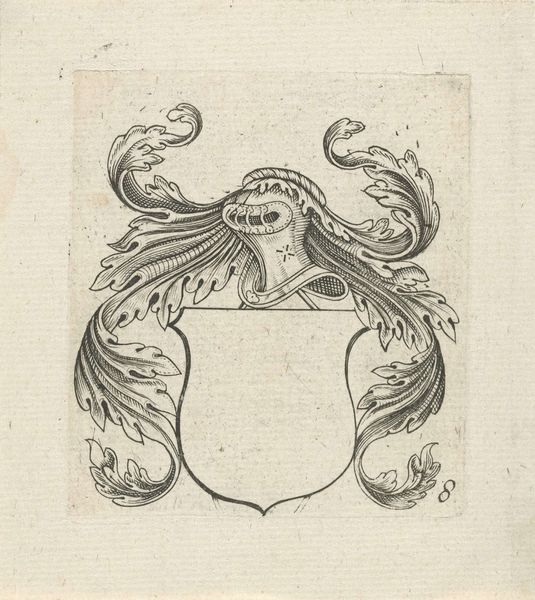

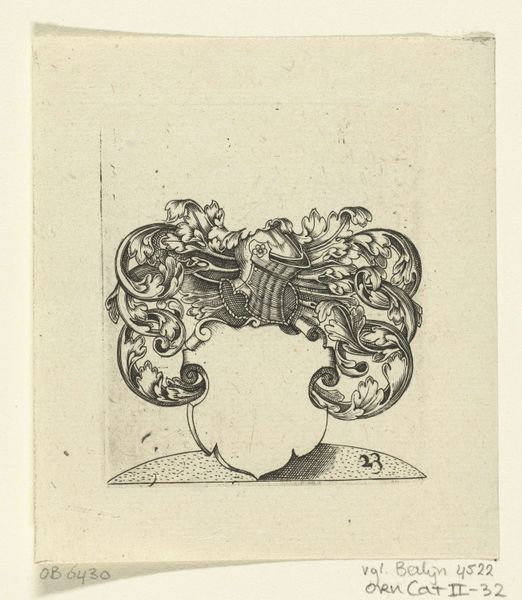

Dimensions: height 68 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum we have "Wapenschild met een helm en bladranken," an anonymous engraving dating back to 1625. It depicts a heraldic shield topped with a helmet and leafy tendrils. Editor: It has a delicate quality; like a whisper from another century. There's a ghostly elegance to its linear precision and symmetrical design that both attracts and repels somehow, you know? Curator: The process of engraving on metal was quite labor intensive, think about it. Each line, each curve, was carefully etched into the plate, suggesting an economy of both visual language and manual effort in production that connects to notions of craftsmanship within Baroque artistic culture. The purpose-built graphic aims for reproduction, likely in multiple instances and on various material supports. Editor: It's funny how an object intended for such clear symbolism - lineage, authority - can, over time, become beautifully ambiguous. The shield is blank, the potential untold stories now silent. That void speaks volumes. Curator: Exactly, and within the Baroque period, these printed heraldic crests played roles both decorative and deeply socio-political. Their production and display underscored relationships among aristocratic families, craft workshops, and even geopolitical configurations within and across states. Editor: When I consider where this engraving probably sat originally – perhaps bound in some ornate volume – its role has completely shifted now, hasn't it? Separated from that original binding, what does it say to us in this setting? Stripped bare from context, it resembles a quiet act of rebellion. Curator: Context matters greatly. Looking at the precise execution here tells me it comes from a context valuing specialized artisan knowledge. These kinds of images shaped consumption practices, reflecting a developing marketplace in the early 17th century. Editor: The visual effect created is more potent for knowing the history of such objects. And maybe this makes me feel more empathetic with the original intentions—these signifiers are potent when we engage with the historical, social reality they came from, rather than purely from within their aesthetic forms alone. Curator: Understanding the interplay of materials and cultural values allows a richer comprehension of these artworks from the past. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing the ghost in the machine allows a glimpse into the soul as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.