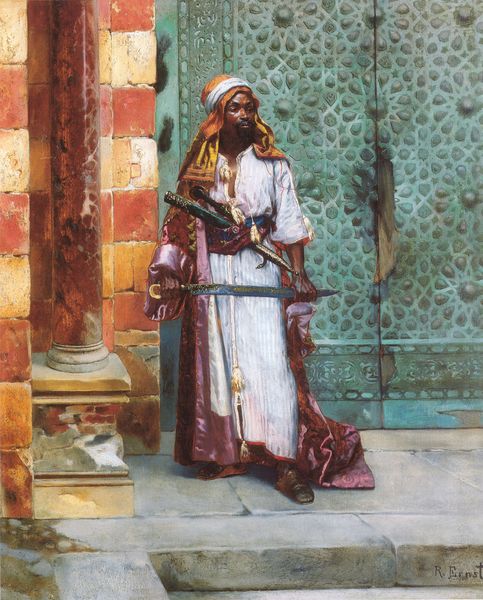

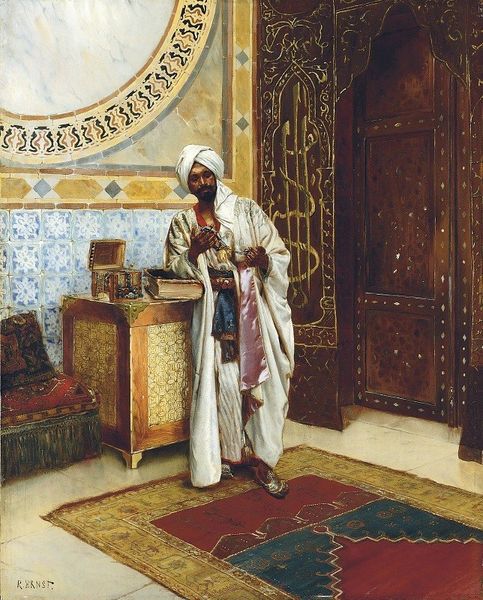

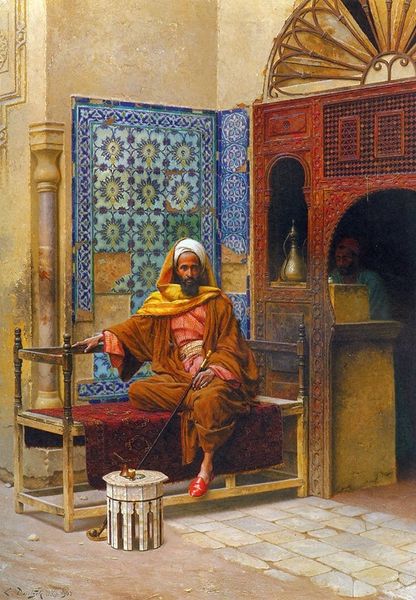

painting

#

portrait

#

painting

#

orientalism

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

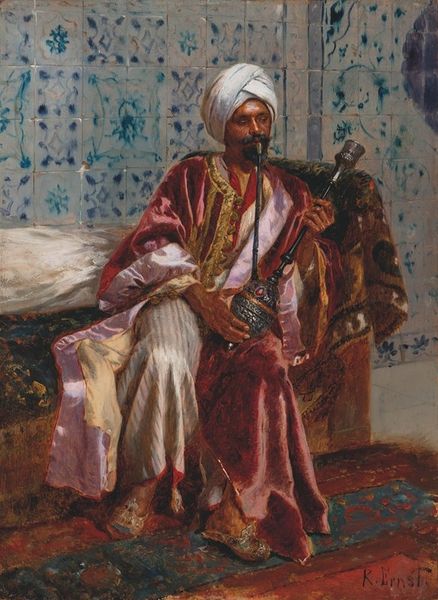

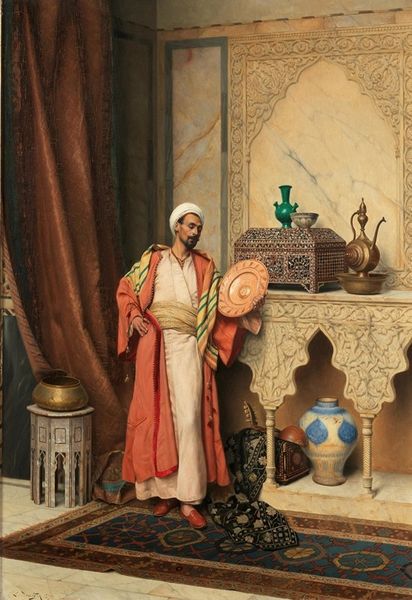

Editor: So, here we have Rudolf Ernst's painting, "Le Fumeur de Narghilé" or "The Narghile Smoker." The opulent textures and colors immediately strike me, giving off an air of languid indulgence. How would you interpret this piece? Curator: Ernst's work falls squarely within Orientalism, a 19th-century art movement. It exoticizes and romanticizes "the East," often reinforcing colonial power structures. How do you think the depicted space contributes to this narrative? Editor: The elaborate tiles, the rich fabrics...it feels like a stage set, emphasizing a constructed vision of the "Orient." Almost like a fantasy, far removed from reality. Curator: Precisely. Ernst never actually visited the Middle East, basing his paintings on photographs and secondhand accounts. It's critical to understand this: his "East" is largely a product of Western imagination, presented to a European audience eager for such exoticized visions. What does this say about the politics of representation inherent in museum display then and now? Editor: It makes you wonder about the intentions of those original viewers – and even our own. Were they appreciating a culture or simply indulging in a prejudiced fantasy? And should museums even be showing these pieces? Curator: Exactly. That question is actively debated within museums today. By grappling with the artwork’s complex history and the potential for reinforcing stereotypes, we can transform the museum from a place of passive viewing into a site of critical engagement with the past. Editor: That’s really shifted my perspective. It's more than just a pretty picture; it’s a loaded cultural artifact. I now see how its initial reception contributed to larger political issues, which modern curators have to reckon with.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.