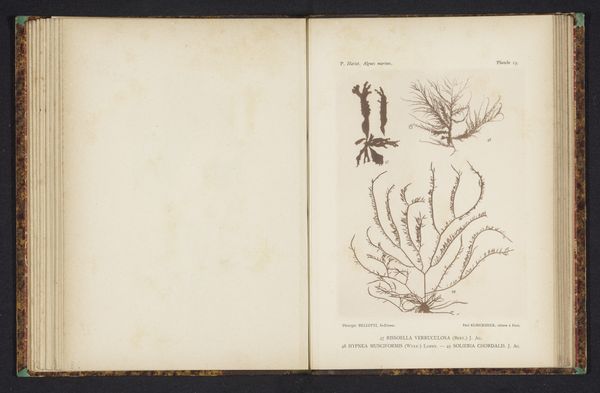

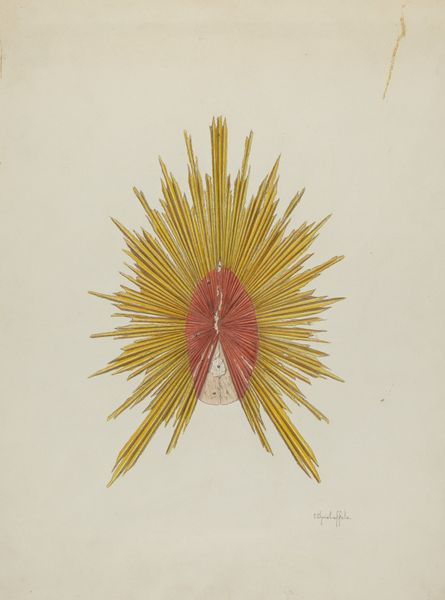

coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

coloured-pencil

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

watercolor

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Egyptian ornament with lotus flower and -bud", made between 1890 and 1922 by Johanna van de Kamer, using watercolour and coloured pencil. The delicate lines and muted tones are quite captivating. What's your perspective on this? Curator: The use of watercolor and colored pencil is interesting here, considering the piece depicts ancient Egyptian motifs. I see this piece reflecting the consumption and reinterpretation of ancient Egyptian art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when archaeological discoveries led to a craze of "Egyptomania". Editor: "Egyptomania"? Curator: Yes, exactly! Think of it as a raw, enthusiastic consumption and then recreation of a far-off land that took the Western world by storm. Here, a common, decorative item such as a floral watercolour carries and reflects on the much wider phenomena of social, almost performative, admiration. Does that make sense? Editor: I think so. You’re suggesting the materials and the rendering, beyond just the subject, signal a specific cultural moment? It's more about how Egyptian art was being used and understood by a European artist rather than a purely aesthetic interpretation. Curator: Precisely. How the lotus, a traditional symbol, is transformed through European modes of production and visual language. It loses a degree of ritualism and becomes integrated into a larger, perhaps diluted artistic setting. This image helps us reconsider artistic labor in light of global cultural exchanges, how materials shape narratives, and even challenge what’s perceived as a ‘pure’ art form like watercolour. Editor: That makes me consider it completely differently! Now, I can really see how this simple study holds a lot of information on cultural perceptions during its time! Thanks. Curator: My pleasure. Thinking through the physical elements really does bring so much more to the image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.