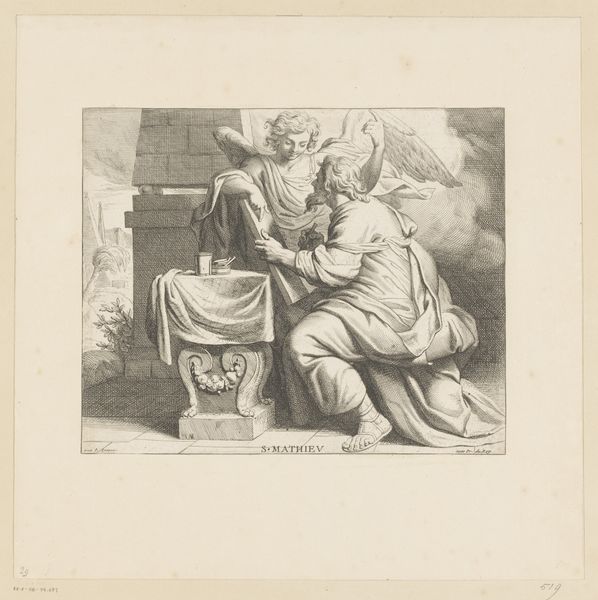

print, etching

#

medieval

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

Dimensions: 140 mm (height) x 161 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: Looking at this etching, "Den angrende Peter," or "The Repentant Peter," created by Carl Bloch in 1882, one immediately notes the somber mood evoked by its delicate lines. What's your initial take? Editor: A heavy feeling. You see the burden of shame etched into his very posture. His hunched figure and bowed head speak volumes about the weight of betrayal, which must have been felt so acutely in a deeply patriarchal and religious world. Curator: Bloch's mastery of etching is fascinating. The contrast between the roughly sketched chickens and Peter's more defined form highlights the labor that went into defining that central figure in all of his disrepair and grief. This image also brings forward questions about class as we explore themes related to work, value, or even worthiness in connection to devotion or religion. Editor: Exactly. Think of Peter, the betrayer—his masculinity threatened in that moment, his status within the early Christian community jeopardized. His remorse isn't just religious; it's profoundly social, particularly with that reminder, those roosters crowing to remind him of his misdeed. His identity is suddenly so linked to that failure in those specific historical conditions. Curator: I think one has to look closely to really note the lines that create depth. It brings to the surface not only an interesting narrative but also material analysis through a clear and somewhat simple printing process that we might take for granted. The artist shows us labor in more ways than one. Editor: Agreed. Bloch really makes us consider: What does it mean to repent, to seek forgiveness within such a structure? He is calling out religious history to ask about its modern value, especially regarding gender roles and how one’s position within faith is earned and taken away based on adherence to its conventions. Curator: It’s intriguing how a print, a reproducible medium, can convey such singular emotional intensity. It blurs the lines between mass production and intimate experience, which perhaps parallels how social norms weigh on personal conscience. Editor: Yes. And looking at how this reflects within a modern frame helps reveal continuities in how those structures and patriarchal expectations of masculinity continue to define self worth even today. Curator: Ultimately, reflecting on Bloch's print invites a layered engagement that highlights both the skills and the critical and creative context behind its making. Editor: Absolutely; situating it within historical power dynamics provides such relevant opportunities to see the world then, and better observe it today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.