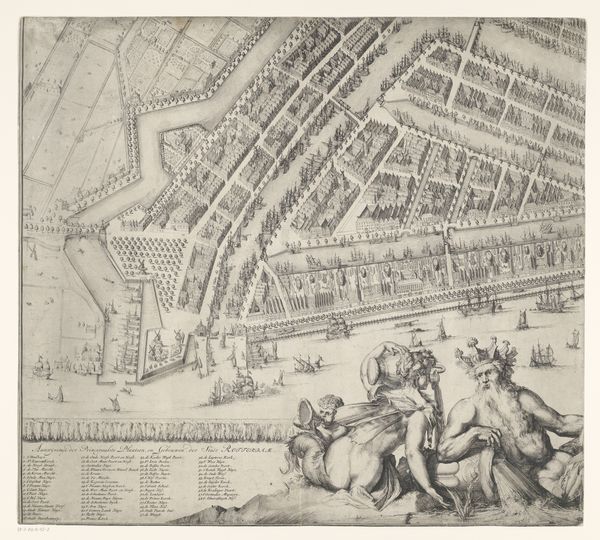

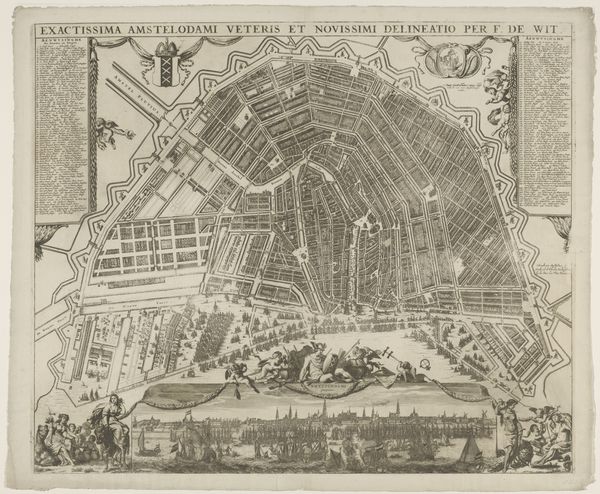

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

perspective

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 522 mm, width 580 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome! We’re looking at "Plattegrond van Rotterdam (deel rechtsonder)", a section of a map of Rotterdam by Romeyn de Hooghe, dating from around 1691 to 1692. It's an engraving, a testament to the precision of the printmaking craft. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the stark contrast. You have this incredibly detailed, almost sterile city plan above, and then this dynamic, allegorical scene bursting from the bottom edge. It feels like two different worlds colliding. Curator: Absolutely. Let’s consider de Hooghe's process. Creating such intricate lines for the cityscape – look at the dockyards and canals, all rendered with exactitude - it’s time-consuming. This wasn't just art; it was information, reflecting Rotterdam's mercantile power and infrastructural advancement. These prints would have circulated widely, serving practical and propagandistic purposes. Editor: Yes, and within that circulation, we must acknowledge how these images participated in shaping identity. Rotterdam’s identity here is undeniably tied to its economic activity, particularly its role in maritime trade. But this overlooks, perhaps obscures, the human cost of that trade – the labor exploitation, the colonial ventures facilitated by these very docks. How does that shadow play against this idealized portrait? Curator: It's an astute observation. The allegory in the foreground with what appears to be personifications of prosperity and abundance does present an idealized vision. The abundance of goods from the colonies entering the harbor of Rotterdam would pass through the hands of labourers in Rotterdam before entering Dutch society. However, without the names or signatures of these labourers who made this possible, they remain anonymous; but in their contribution to society, they remain visible through material things, in the traces they left in Rotterdam’s industrial and social history. Editor: The black figure adds a disquieting dimension too. Given the period, how can we not consider his presence within the narrative of burgeoning Dutch colonialism and its complex, often brutal power dynamics? His passive, almost reclining pose reinforces certain racial hierarchies that were being solidified at the time through economic exploitation. Curator: That’s well-considered. The material realities of producing and distributing an image like this cannot be divorced from the social realities of the time. Thank you, this exploration opens up ways to interpret the complex relationships that helped shape Dutch society. Editor: Indeed. These historical documents require constant critical engagement. They're not passive reflections of the past but active participants in shaping our present understanding of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.