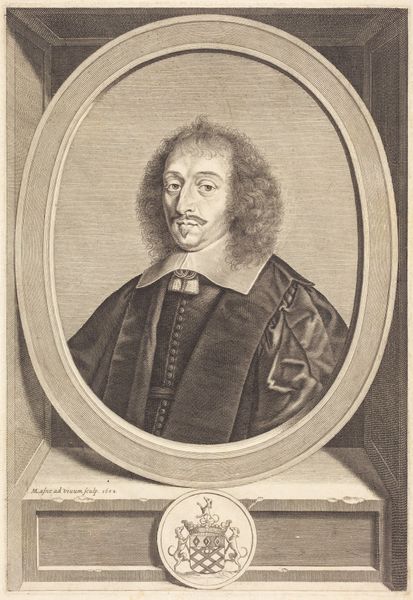

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 291 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The artwork before us is a portrait of Blaise Pascal by Gérard Edelinck, made sometime between 1666 and 1707. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. The print employs the engraving medium. Editor: The engraving gives Pascal an almost spectral appearance. His gaze is intense, though tempered, the details meticulously rendered lending a severity that clashes oddly with the soft curls of his hair. Curator: It's important to consider Edelinck’s process here, working as an engraver during this period required tremendous skill and an understanding of material properties. This wasn't merely about artistic expression but the precise and replicable transfer of an image. Think about the physical act of engraving – the labor, the tools. Editor: Labor, yes, but also who gets memorialized and how. Pascal wasn't just any person. This image signifies his status as a philosopher and mathematician, situating him within the intellectual currents of the 17th century. That oval frame, the inscription giving his age—they all speak to the construction of his identity and legacy. Curator: Right, but even the concept of portraiture itself reflects socioeconomic factors of production. It speaks to a specific economy, where representations are commodities, highlighting a move toward individuality and image consumption during this time. And the very choice of engraving speaks volumes about replication, how an individual image can enter the popular realm of exchange, influencing his reputation, maybe solidifying it. Editor: Absolutely. The means of production affect that representation. Look closely at the texture and lines. Edelinck’s method translates Pascal into a symbol of intellectual authority and the scientific revolution. His portrait carries within it all the tensions and aspirations of that era, its relationship to theology and reason and class structures. It’s a cultural artifact reflecting its historical conditions, down to the details of his clothing. Curator: That is what speaks to me: Edelinck's artistic means made Pascal available on some level to a population, and the consumption of it shapes the Pascal-image in social circulation. Editor: A fitting perspective on Pascal's legacy. It reminds us that seeing isn't always believing – it's interpreting. Curator: Precisely. An image is nothing if it isn't made available for engagement by the masses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.