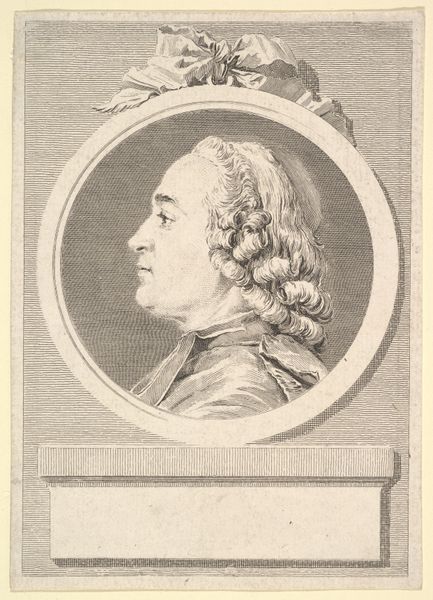

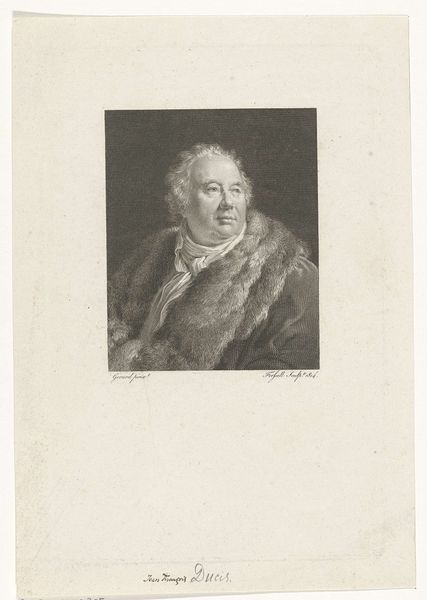

Portræt af den schweiziske naturvidenskabsmand og filosof Charles Bonnet (1720-93) 1779

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: 111 mm (height) x 83 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This drawing by Jens Juel, made in 1779, portrays the Swiss naturalist and philosopher Charles Bonnet. What strikes you first about it? Editor: It's the delicate quality of the pencil work. Look how the light falls softly on his face, and the subtle shading that gives such volume to his wig. There's a real tangible sense of the material craft in the mark-making. Curator: Indeed. Considering Bonnet's work in natural philosophy and how he wrestled with questions of pre-existence and transformation, the wig is particularly significant. These elite visual markers held immense power. Its construction speaks to labor and luxury in contrast to Bonnet’s scientific endeavors. How might we understand his philosophies of transformation alongside this very constructed outward appearance? Editor: The precision of the lines suggests a meticulous hand. Each stroke must have been deliberate, mirroring the calculated world of science during the Enlightenment, although that world was highly patriarchal and hierarchical. And beyond aesthetics, how were pencils actually manufactured in this era? Were materials sourced ethically? Who was involved in the distribution networks? The drawing is, literally, a product. Curator: These are critical considerations. As an advocate for preformationism, Bonnet believed that all organisms existed in miniature form from the beginning of time. Looking at the subject of this portrait through the lens of gender and power, one wonders to what extent such theories served the existing social and gendered order. Where did this subject stand in these complex conversations, especially as these issues impacted women? Editor: Perhaps this detailed approach speaks not only to Enlightenment ideals but also to the intense commodification of materials and resources at the time. How do such precise tools change what and how art is created? The constraints themselves have impact on creative processes. Curator: Absolutely. Looking closely and reflecting on Bonnet, both subject and theory, makes one acutely aware of the intellectual landscape in the late 18th century. It pushes us to think about our own biases in interpreting the past and how notions of the ‘natural’ have been historically weaponized. Editor: I concur. By considering both the material circumstances of its production and how it circulates, we understand that the work provides an important visual tool to interpret its period and place in time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.