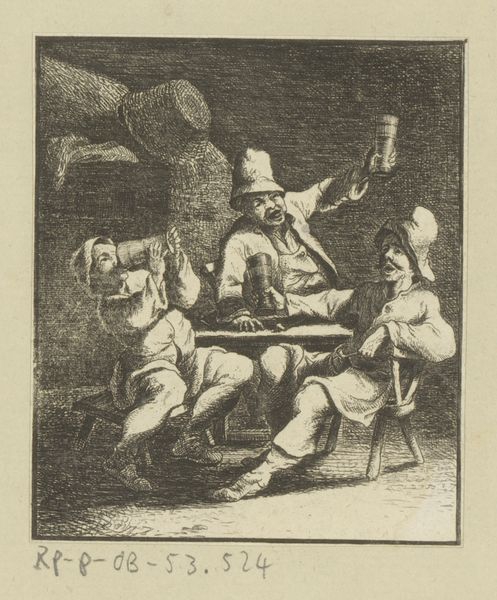

print, etching

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 144 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

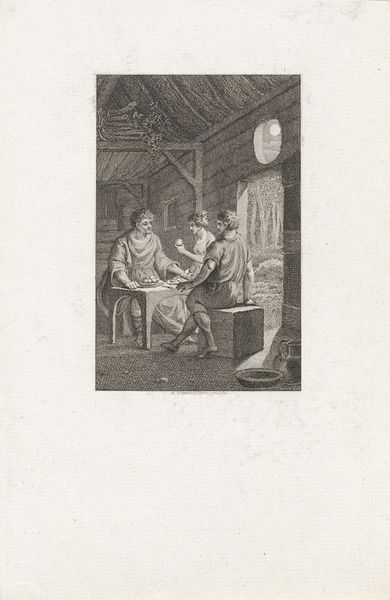

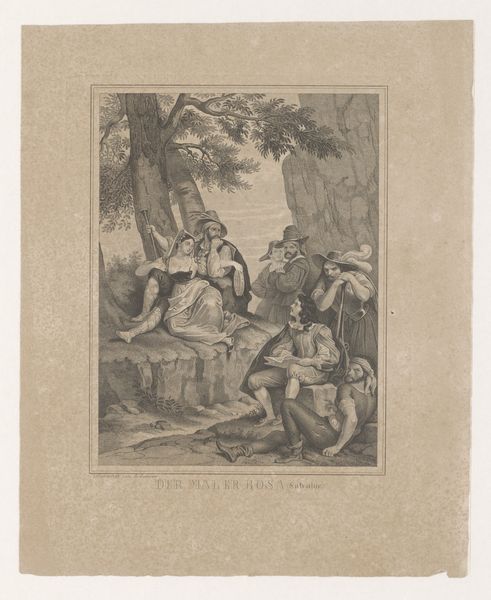

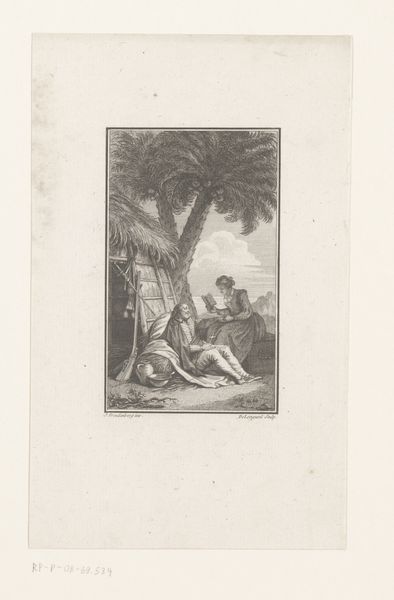

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to Johannes Arnoldus Boland’s “Resting Travelers,” created between 1875 and 1876. It’s an etching, a kind of printmaking, and I’m immediately drawn to how the labor involved shapes the final image. Editor: This evokes a certain nostalgia, doesn’t it? Like eavesdropping on a story in an old, cozy inn. The soft textures of the etching create a kind of intimate, hushed atmosphere. Curator: Absolutely, and that feeling comes from the intensive process of etching, each line painstakingly drawn into the metal plate. The labor involved in reproducing the work should be appreciated. Consider how prints allowed images to be widely distributed and consumed. Editor: It reminds me a little bit of a well-loved memory, the kind where the details are soft around the edges. I wonder, were these travelers successful? Are they returning home with goods, or are they just seeking solace for a journey gone sour? Curator: What’s fascinating is the realism style depicting everyday scenes of genre-painting, reflecting shifts in art consumption toward narrative-art. The subjects aren't elevated historical figures or mythological heroes; instead, it’s common folk in a common situation. We are invited into their world. Editor: And I want to understand more about these hunters or tradesmen...there’s an innate storytelling ability woven into Boland's use of shadow. They speak without words, hinting at deeper tales hidden just beneath the surface. Curator: This technique echoes realism's concern with depicting the material conditions of everyday life. We're confronted with laborers and travelers, perhaps pausing amidst a trade expedition or simply resting on a break during harvest season. Editor: Thinking about that old engraving style with figures resting together outside and sharing stories reminds me of the community-centered life during those times, contrasting with our sometimes isolating modern existence. Curator: In short, we get not just the figures represented but how their depiction interacts within their own social fabric of production and reception. Editor: Precisely. And I love that we can extract so much from one small snapshot of lives that took place nearly two centuries ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.