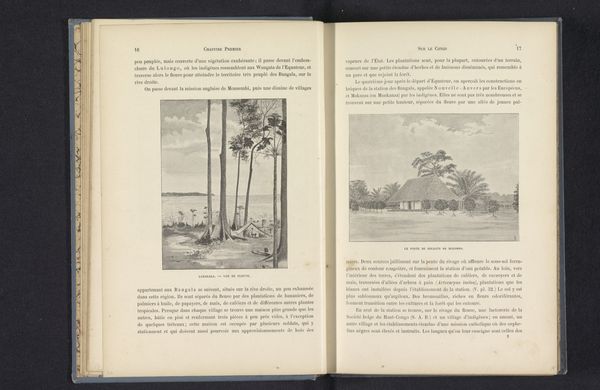

Fotoreproductie van een tekening, voorstellende een gezicht op een eiland in de Congorivier nabij Bolobo before 1899

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper

#

drawing

#

paper non-digital material

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is an anonymous reproduction of a drawing, dating back to before 1899. It depicts a view of an island in the Congo River near Bolobo. It’s rendered with such precise detail… it almost feels like a photograph. What social and historical narratives are embedded within this work? Curator: Well, seeing this image, I'm immediately drawn to the concept of "representation." Whose gaze are we seeing this landscape through? This image was created before 1899, during the height of European colonialism in the Congo. Considering this, the seemingly objective depiction of the landscape becomes charged with power dynamics. Editor: So, it’s not just a landscape, but a document reflecting a particular viewpoint? Curator: Precisely. It’s important to question what this image *omits*. Where are the Congolese people in this picture? What does this absence tell us about the colonial agenda of the time, prioritizing a narrative of exploration and dominion over Indigenous presence and ownership? Editor: It makes me think about the power of visual narratives in shaping perceptions and justifying colonial expansion. It is also thought-provoking how a drawing created through engraving makes the subject even more distant, objective, and scientific-looking. Curator: Yes, the technique reinforces that sense of detachment and "objective" observation. But this piece can serve as a tool for understanding the visual language used to legitimize colonial control. How can we re-examine historical narratives by recognizing the biases inherent in these images? Editor: Looking at this piece has shown me how crucial it is to analyze historical artworks through a critical lens, considering their historical context. Curator: Exactly. We need to recognize art not just for its aesthetic qualities, but as an intersection for understanding power, representation, and social structures. It allows us to challenge colonial perspectives and amplify the voices of those who have been historically marginalized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.