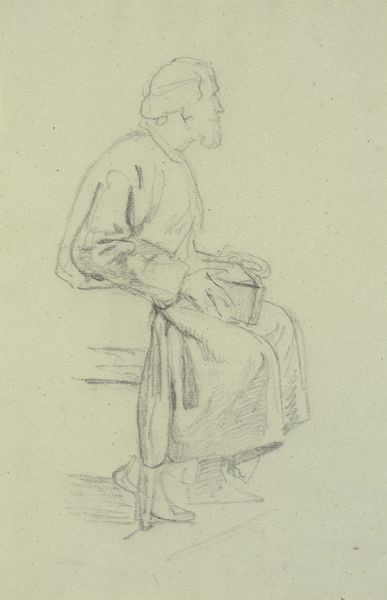

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: 228 mm (height) x 169 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This is Wilhelm Marstrand's 1851 pencil drawing, "Siddende svensk kone, knæstykke," which translates to "Seated Swedish Woman, Knee Piece." Editor: The drawing's pale tonality lends a certain airiness. Almost like she’s sketched into existence rather than fully present. There’s something subtly melancholic about it too, wouldn't you say? Curator: Absolutely. Marstrand was working during a period of increasing social consciousness and national romanticism. Representations of everyday people, especially women from various regions, became a way to explore ideas about national identity and cultural heritage. This "Swedish Woman" isn't just an individual; she's meant to evoke a sense of place and belonging. Editor: I see that. I’m especially drawn to her hands. They seem weathered and speak to a life of work, a subtle detail amidst the overall understated presentation. You know, the sketchiness reminds me of half-formed memories – familiar but not completely grasped. Curator: That resonates with the use of Realism during that time; focusing on a faithful depiction of the physical appearance, but I would suggest the clothing gives us important information. The details around her headscarf, blouse, and jacket communicate her status within a certain working class. Her clothing represents a lived experience beyond what's immediately visible on the surface. Editor: Perhaps that quietness allows us space to imagine her inner world – a kind of silent partnership in observation. It reminds me how art can act like a bridge across time and cultures, even with simple things like a pencil drawing of a woman seated long ago. Curator: Precisely, and it highlights how artworks, even seemingly simple portraits, are always embedded within a web of social and historical forces. They serve as powerful reminders of the past and can inspire dialogue and introspection today. Editor: I guess that’s why the simple act of looking—really looking—at art becomes a rebellious, intimate conversation with history and ourselves, right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.