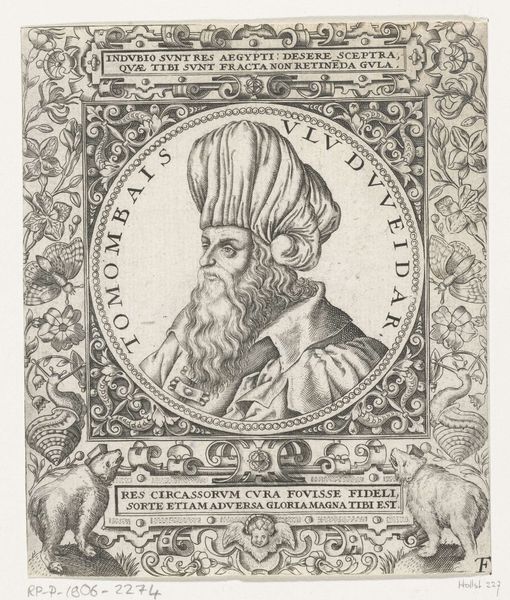

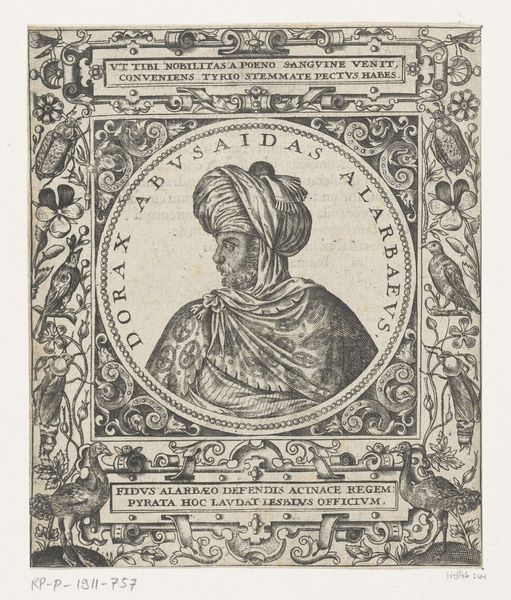

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

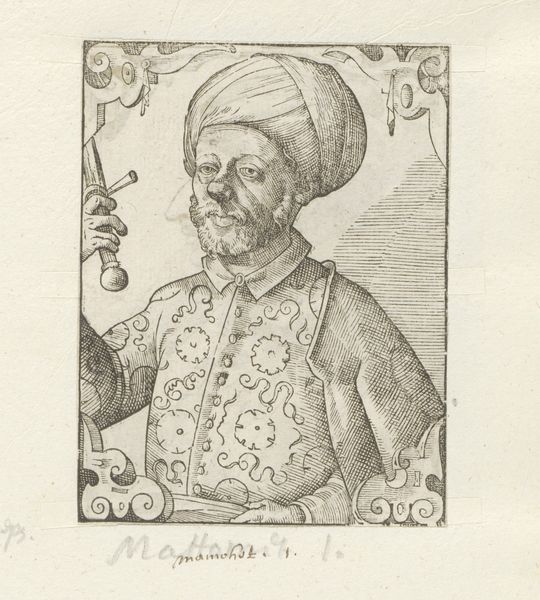

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

islamic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, dating from 1596, is a portrait of Sultan Musa Khan by Theodor de Bry, held here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s a fantastic example of how early printmaking captured and disseminated images of important figures across Europe. Editor: My initial impression is the contrast between the central image and the detailed ornamentation around it. It's as though two different artistic intentions are vying for attention within the same space. Curator: Absolutely, and the ornamentation itself is laden with symbolic meaning. Notice the frame with animals and vines, a traditional display of wealth and power. Each animal was specifically chosen to represent Musa Khan’s persona and position. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the material process itself. This isn't just a portrait; it's a repeatable image created through meticulous labor. Engraving involves carefully incising lines into a metal plate, then inking it to produce prints. Each line required physical exertion. Curator: Precisely! And the lines create symbolic dimensions. For example, the Sultan's turban isn't merely headwear, it’s a symbolic crown, the elaborate folds representing spiritual authority. Similarly, the direction of his gaze can suggest confidence and leadership, aligning with Western understandings of power. Editor: Speaking of power, how might the materials themselves have contributed to its image construction? Copper, the most common printing plate material, could become quite costly. This expense would impact the work's accessibility and perhaps reinforce social distinctions among those who would have come across such prints. Curator: The Latin inscription above the portrait even hints at the nature of the subject and his story: ‘Quid Melicvm Vezirem invit fecisse, tvo si te prive Patrio proditor Imperio’, likely highlighting some betrayal or conspiracy, further illustrating Musa Khan’s significance as both an historical figure and a subject of European fascination. The verses below reiterate ideas of servitude. Editor: Indeed, even the paper quality chosen for the print run affects its longevity, influencing how well the work holds its information over time, something so essential for spreading imagery and ideology during this era. Considering this really brings forward how the Sultan was viewed across the continent. Curator: The combination of classical portraiture, the dense, active imagery, and choice of inscription shows what cross-cultural exchange looked like in 16th-century Europe. We’ve touched on visual language as a symbolic representation, of cultural identity, and of power itself. Editor: Right. And through understanding of printmaking as laborious practice embedded within distribution networks, we have insight to the power relations and commercial considerations driving this portrayal of Sultan Musa Khan.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.