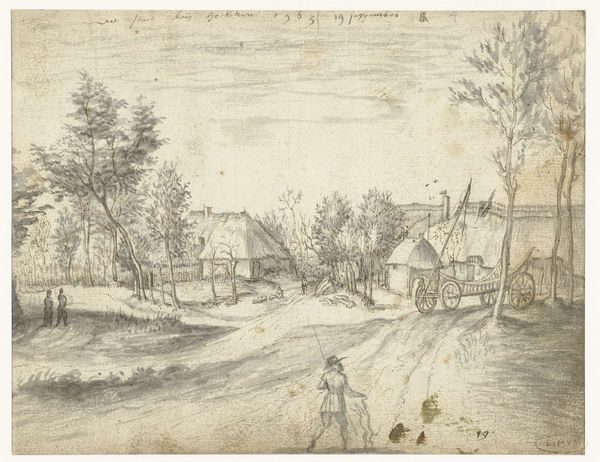

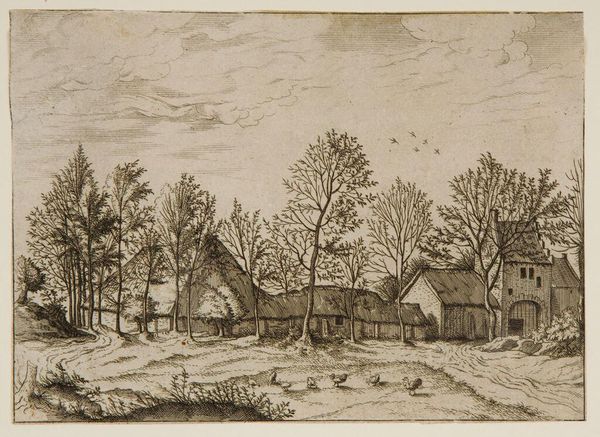

drawing, print, etching, intaglio, paper, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

paper

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 204 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is a print from around 1560, "Village Street with Cattle and a Shepherd," attributed to Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum. Editor: It feels incredibly... peaceful. The delicate lines, the understated depiction of everyday rural life… it’s like a fleeting glimpse into another era. I immediately think about labor conditions and land usage in Northern Europe. Curator: Absolutely. This piece provides insight into the social landscape of the time. The etching technique itself, combined with engraving, reflects a particular moment in printmaking history—a period when these processes facilitated wider distribution of images and ideas. Consider, also, the burgeoning merchant class. Editor: And we should think about what printmaking *means*. It's inherently reproductive, tied to labor and capital... How were these engravings circulated? Who owned them? Did they reflect the lives of the herders shown or romanticize those lives for the consumption of the emerging bourgeoisie? I think the answers change how we perceive this quiet scene. Curator: It prompts fascinating questions about audience and artistic intent. Note how the composition focuses not just on the pastoral scene but on the entire village street, inviting interpretations around community and daily life. The details are fascinating: those thatched roofs on the houses. They signal the relationship between human craft and locally sourced materials. Editor: Those details also highlight something very specific: craft and building are labor. We have to ask, then, what lives, what materials, were devalued to produce this seemingly tranquil image? Consider the exploitation required for thatch roof production or raising livestock, and it suddenly feels a bit less idyllic. The quiet itself becomes unsettling. Curator: That’s a compelling tension – the artwork simultaneously projecting bucolic simplicity and, as you suggest, obscuring underlying structures of power. Examining it through both a historical lens, to understand its cultural moment, and a contemporary theoretical perspective helps reveal those complexities. Editor: Indeed, understanding the material conditions and the reproductive nature of printmaking allows us to confront some of those harder, yet more critical, truths behind idealized visions of the past. Curator: I'm struck, as always, by how interrogating art from various viewpoints creates much richer appreciation. Editor: Agreed; it becomes less a passive consumption of an image and more an active investigation of its context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.