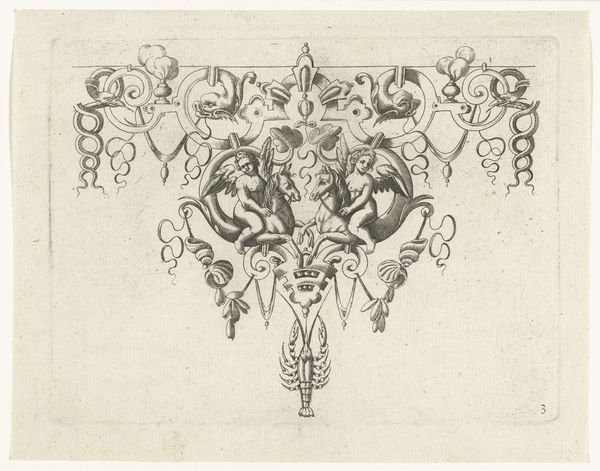

graphic-art, ornament, print, engraving

#

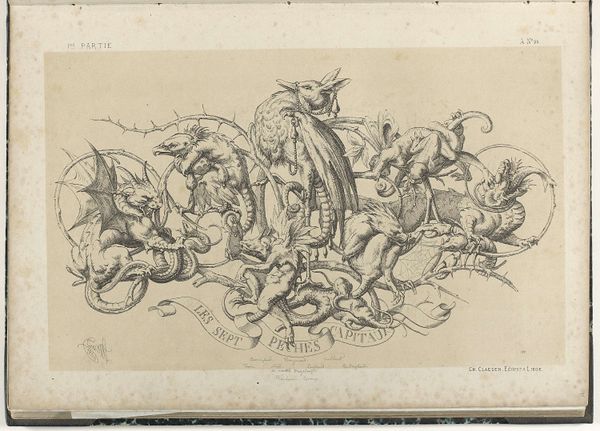

graphic-art

#

ornament

#

baroque

# print

#

geometric

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 66 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

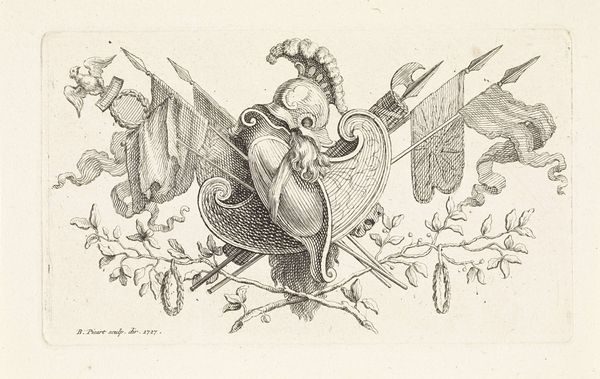

Curator: Bernard Picart's "Ornament met twee fasces," created sometime between 1683 and 1733, employs engraving to depict an ornamental design. The prints on display here in the Rijksmuseum. What is your first take on this engraving? Editor: Immediately, the symbolism hits hard. Fascism's historical baggage looms large, despite the Baroque flourishes. The precision feels...cold. Curator: The fasces are indeed central here, rendered with meticulous detail. We can think about these prints through their materiality: paper, ink, the engraver's tools. These were likely mass-produced, serving as models for artisans working in various media. Think furniture makers or silversmiths. Editor: That reproducibility complicates things. While seemingly decorative, its original context could imply an endorsement of power structures. The ornament itself might have functioned to normalize, and disseminate an ideology—privileging authority through these crisp lines. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the labor involved in the etching and printing. Picart and his workshop would have relied on skilled artisans. Their labour and level of skill shaped how efficiently and accessibly they delivered their product. What was consumed widely, becoming a trend. Editor: Which circles back to consumption and the decorative arts. How were these images consumed? And who had access? Were these emblems destined for elite circles reinforcing social stratification? Or were these deployed on a mass scale across various strata of society to cement allegiances to a singular ideal? Curator: It's both, likely. Baroque ornament was highly fashionable. Think about how easily these could be translated into embroidery patterns. But those associations you raised of how the image could serve elite interests are, well, hard to overlook, right? These images are themselves commodities circulating within specific economies of taste and power. Editor: Exactly. An intriguing example of how seemingly innocuous designs can become laden with sociopolitical weight. I think this engraving demands a level of visual literacy. Understanding how and why symbols endure or how and why their significance has shifted is key. Curator: Looking closely at Picart's engraving makes one newly conscious of the materials involved, but beyond just process is also where it circulated. Editor: It serves as a chilling reminder how aesthetics are rarely apolitical, even—or especially—in ornament.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.