photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 191 mm, width 244 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

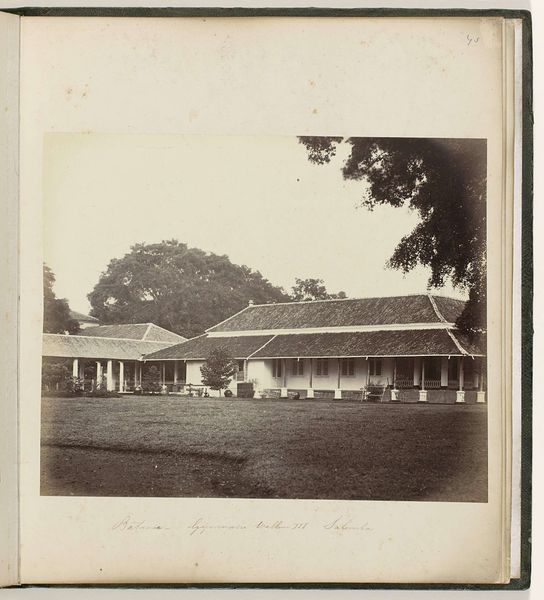

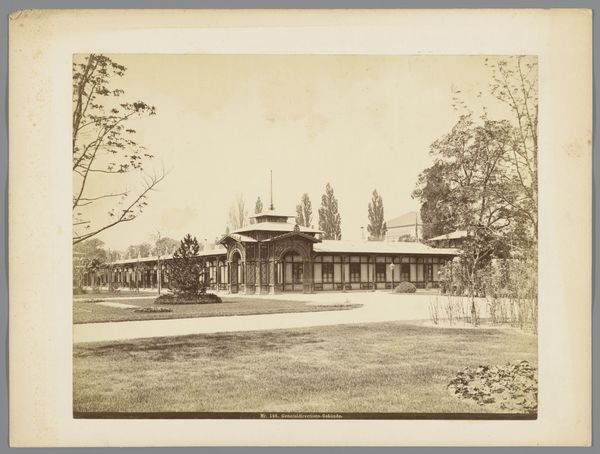

Curator: Woodbury & Page, sometime between 1857 and 1870, captured this scene in a piece called "Gezelschap met bedienden voor een huis op Java" -- that's "Company with servants in front of a house in Java." This albumen print, a style very common for photography in that period, is currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What immediately strikes me is the way the imposing colonial architecture is framed by these ancient trees. It’s almost as if nature is bearing witness to a particular chapter of human history unfolding in Java. Curator: The very composition highlights colonial power structures. See how the figures, presumably European colonizers and their Javanese servants, are carefully arranged, signifying their respective roles in society? Photography at the time, especially by studios like Woodbury & Page, actively helped disseminate this hierarchical social order, solidifying those perceptions for viewers back home. Editor: The play of light is so interesting too. That massive banyan tree, with its intricate root system, dominates the left side, and the house almost nestles within it. To me it reads as a kind of resistance. Even as the colonial project tries to assert its order, the natural world stubbornly retains its grandeur, and exerts a certain weight over everything. The long veranda also reads almost like a stage, carefully constructed to make those colonial structures clearly visible to any onlooker. Curator: It's easy to romanticize those lush trees, but think about their role here. Are they picturesque backdrops, or subtle markers of displacement? Landscape painting during the colonial era often employed exoticized natural scenery to reinforce a narrative of foreign dominance and the assumed taming of nature itself. Editor: Yes, but nature can hold multiple symbolic layers simultaneously. The tree can represent resilience, endurance, even defiance. Consider the enduring power of sacred groves and the traditional connection that many cultures had to nature—those symbolisms don’t just vanish because a new social structure emerges. Curator: Absolutely, and acknowledging those diverse perspectives is crucial. It avoids painting colonial era photography with too broad a brush. Editor: Exactly. We can look at those familiar colonial representations with new appreciation now, not only seeing those long entrenched social narratives but equally the indigenous perspectives always subtly undermining them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.