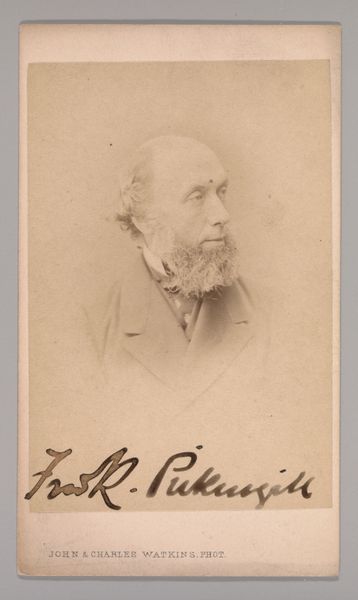

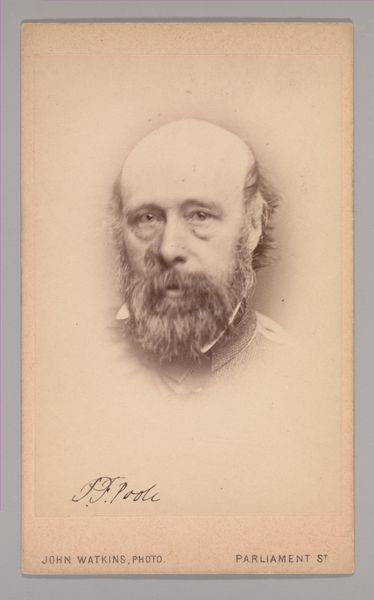

![[Richard Redgrave] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzNiZDc5YmYxLTZiMzEtNDU0OS1iYWY4LWUzOWIwNzU0Y2NjNy8zYmQ3OWJmMS02YjMxLTQ1NDktYmFmOC1lMzliMDc1NGNjYzdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

men

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

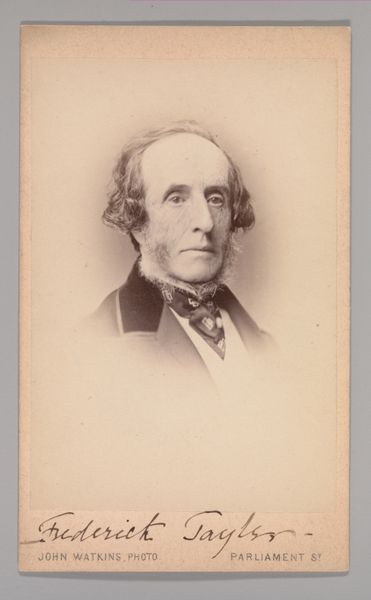

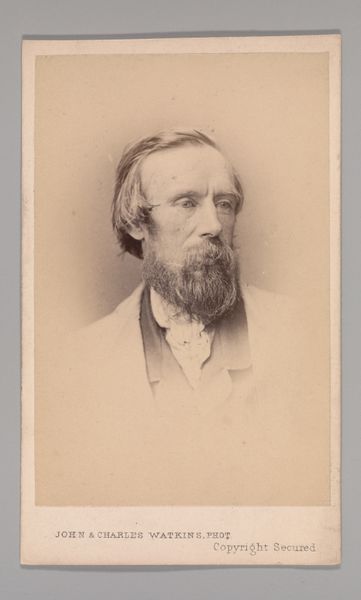

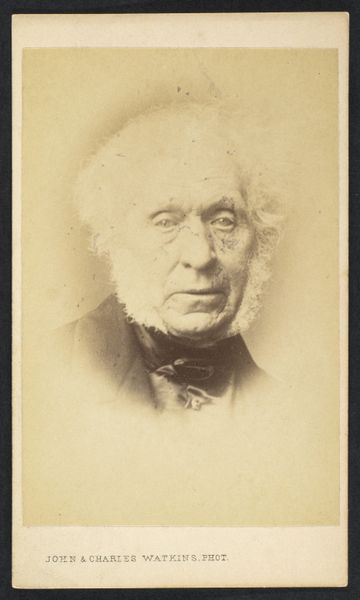

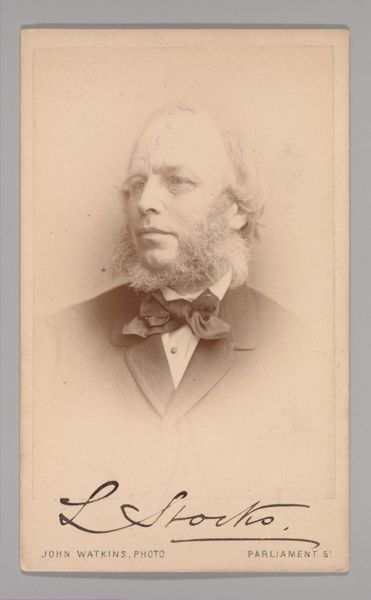

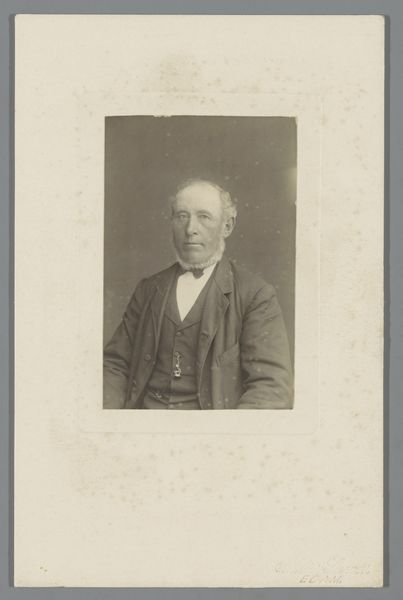

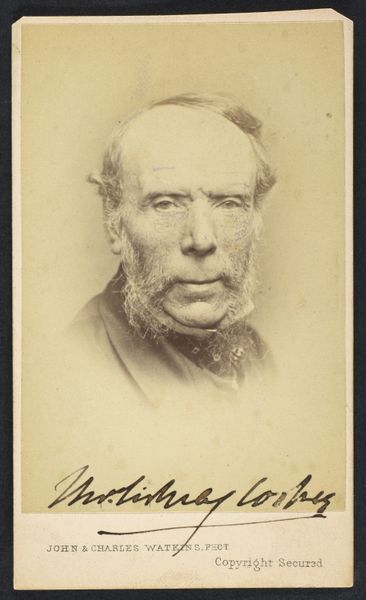

Editor: We're looking at a gelatin-silver print from the 1860s, simply titled "[Richard Redgrave]". It’s a portrait by John and Charles Watkins, and it's currently residing at the Met. There's a really serene, almost gentle quality to it that I find compelling. What catches your eye in this image? Curator: Oh, this fellow could step right out of a Victorian novel, couldn't he? The slightly soft focus almost lends a painterly effect. I'm immediately drawn to the quiet confidence in his eyes. Tell me, what do you make of the way the light falls across his face, and indeed his signature? Does it not remind you of something grand and confident, and almost royal in style, even? Editor: I see what you mean! The way his name is prominently displayed does add to that sense of importance. It is bold, and artistic. It does create a powerful impression about who this is, without knowing. I'm curious about the historical context, though. What would something like this have signified in its time? Curator: Wonderful question. Back then, photography was increasingly democratizing portraiture. Think about it, painted portraits were usually the domain of the elite, but this offered access to having a representation of yourself and your loved ones to a burgeoning middle class. There’s a certain understated elegance, though, that suggests Redgrave, though photographed, still held a place of considerable standing. It makes one wonder about access. Who *was* this person? What power and money did he weild to allow this snapshot of an important man's history to come to be? Editor: That’s fascinating! It is almost like it sits in this liminal space. Thanks so much. I never considered that photography offered accessibility, in its time. Curator: My pleasure. The photograph’s just not a picture but a record, and a cultural signifier isn’t it? Always lovely to share musings on the visual, so accessible now, yet, paradoxically, so historically elusive and rarified.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.