plein-air, oil-paint

#

tree

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

river

#

oil painting

#

forest

#

romanticism

#

water

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 142.2 x 120 cm

Copyright: Public domain

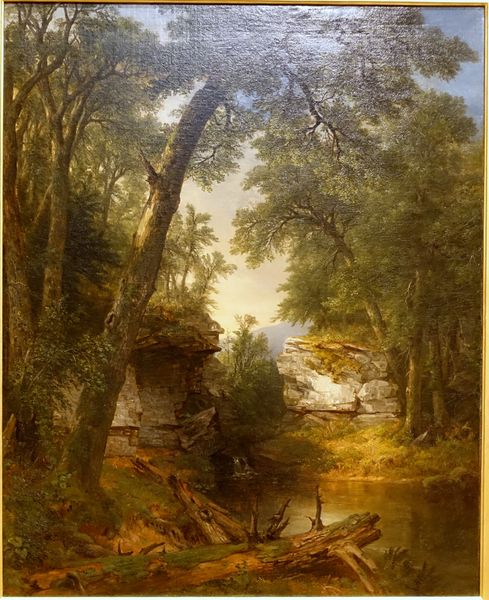

Curator: Looking at this image, my eye is drawn to the sheer physicality of it—the visible brushstrokes, the palpable textures. Editor: It’s rather picturesque, isn't it? The Lock, painted by John Constable in 1824 and displayed here at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, depicts a very particular vision of rural England. There’s a certain serenity, a nostalgia even, evoked by this scene of everyday life. Curator: Serenity, yes, but also labor. Look at the construction of that lock. Constable’s choice of oil paint on canvas emphasizes the materiality of both the scene and the representation. The visible wood grain, the worn textures—they speak to the hard work inherent in managing the waterways and moving resources across the landscape. We often gloss over that labor in Romantic landscapes, don't we? Editor: We often do, and I think that points to how these images become important vehicles for articulating social values. The romanticized depiction of the English countryside provided a comforting vision for the rising middle class. Constable was able to capitalize on this demand and gain patronage. He presents a harmonious relationship between the people and the land. But was this truly representative, or was it selectively crafted to reflect the idealized narratives of the period? Curator: The material realities often complicate such idealizations. Constable made on-site oil sketches which directly captured atmospheric conditions; there’s something revolutionary in his attention to the quotidian, ordinary making process, from paint to river barges. Think about how industrialization was shifting the landscape, displacing people and altering the very materials of daily existence. Editor: Precisely. These depictions helped to create a sense of national identity rooted in the countryside, and Constable very astutely presented a national identity through such lenses of his period. I wonder if those viewing these artworks understood how the politics of image-making shape our perception of history. Curator: Well, it prompts a conversation, doesn’t it? About the layers of representation, about labor and its relationship to the romanticized landscape. Editor: Indeed. It reminds us that beauty can also be a constructed narrative, masking, revealing, and reinterpreting realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.