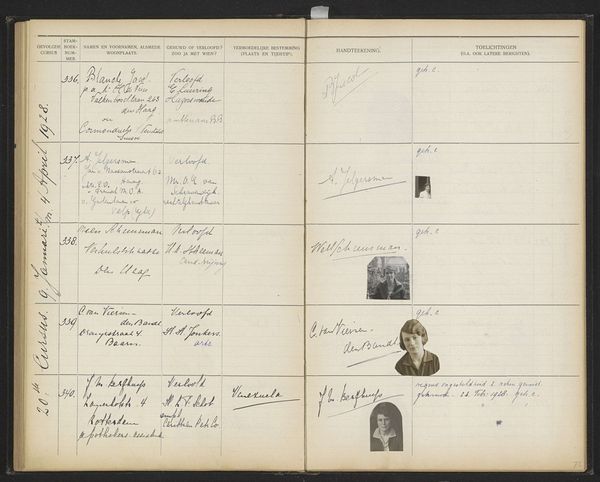

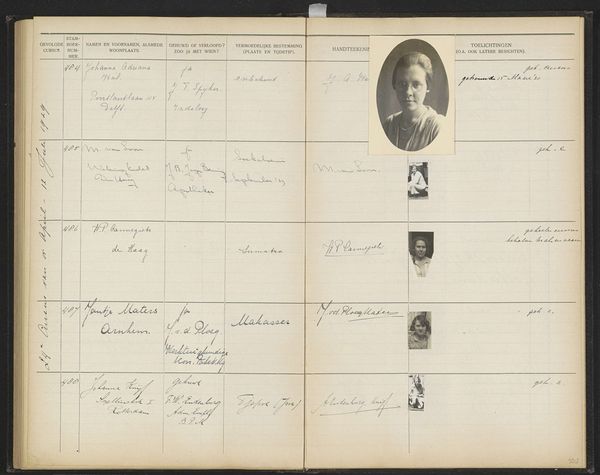

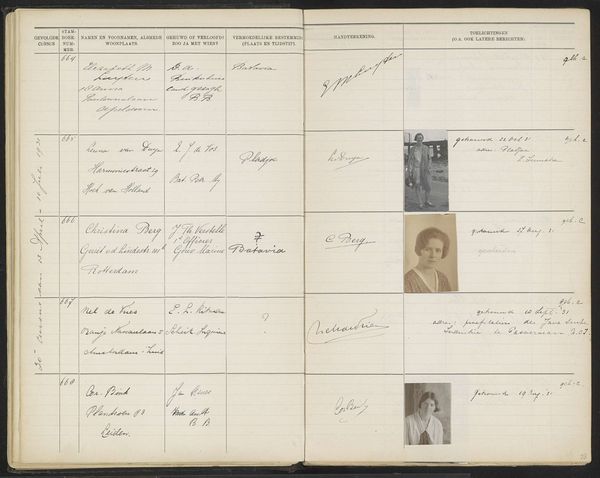

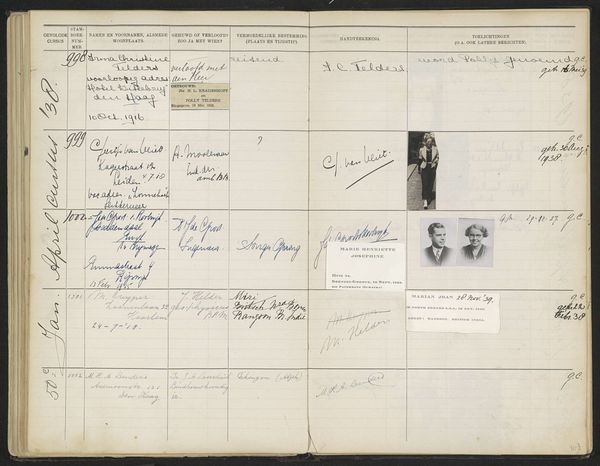

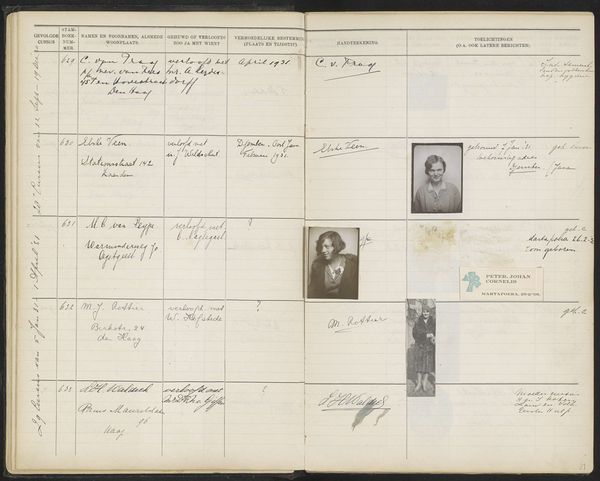

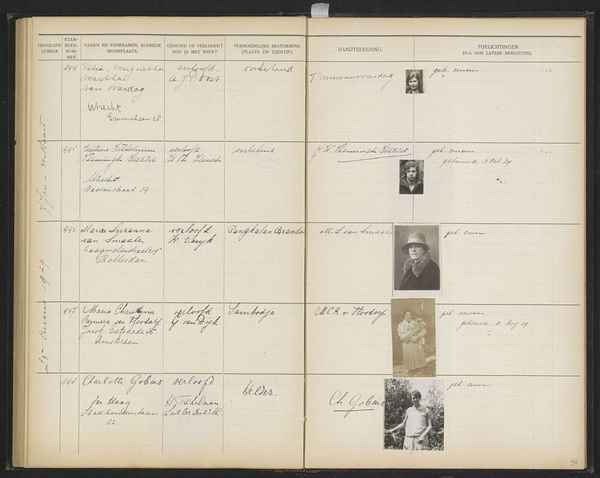

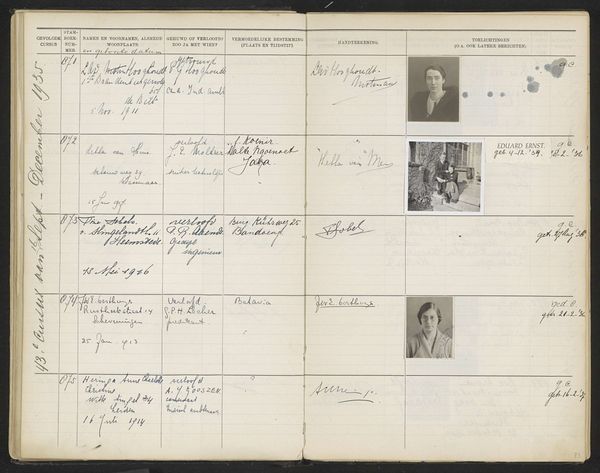

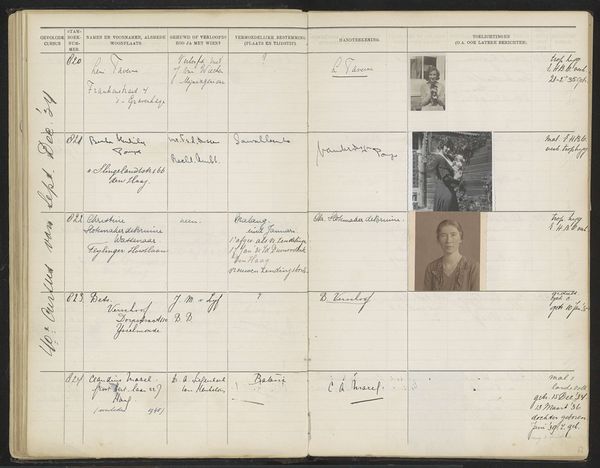

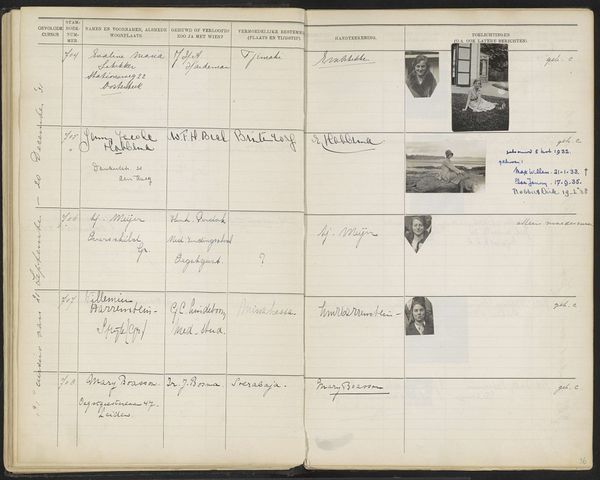

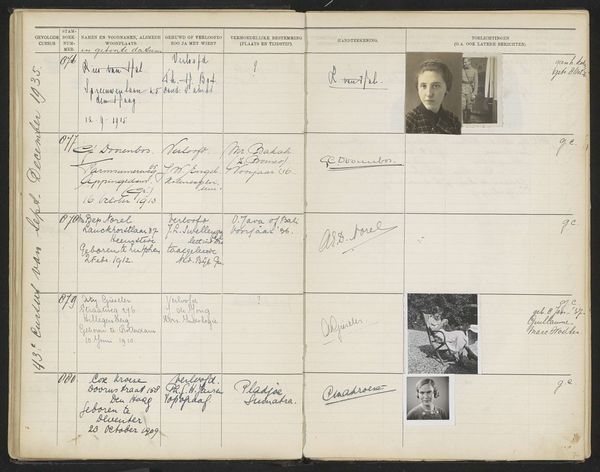

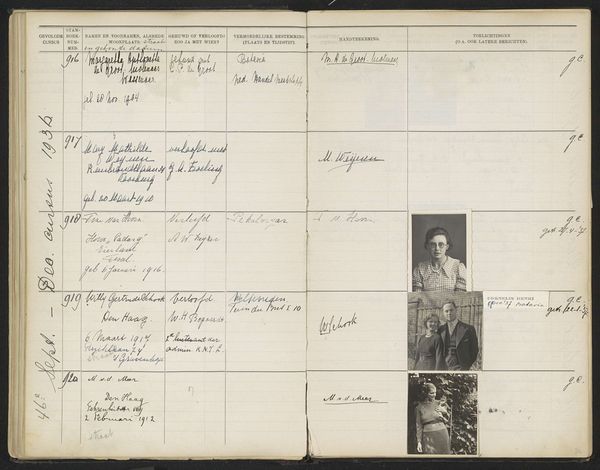

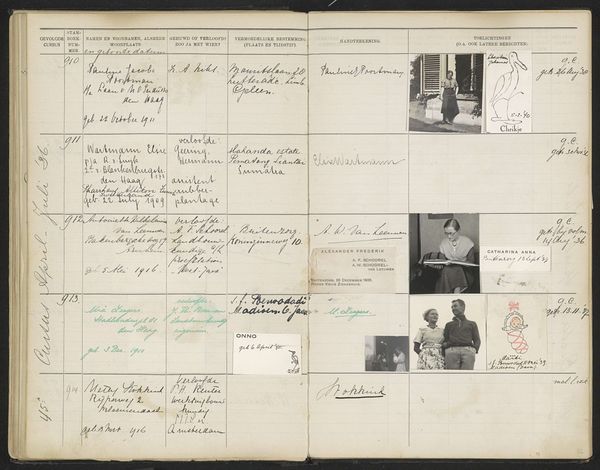

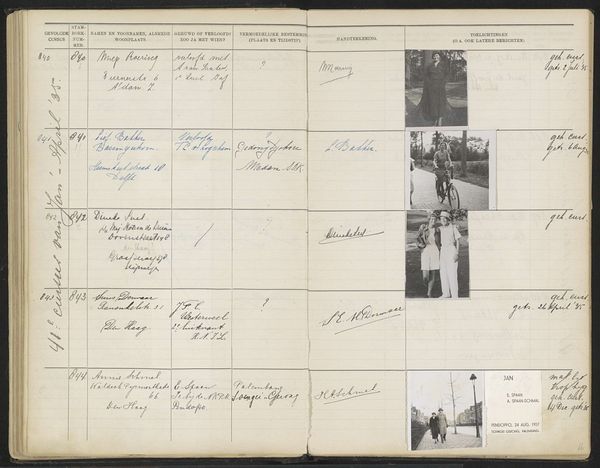

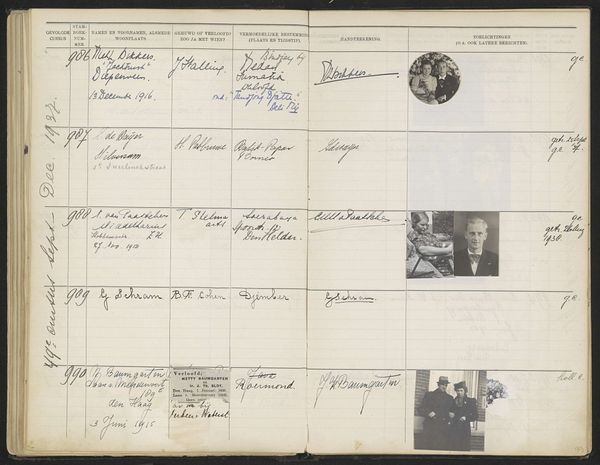

Blad 100 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel I (1921-1929) Possibly 1929

0:00

0:00

paper, photography, ink

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

paper

#

photography

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 440 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have “Blad 100 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel I (1921-1929)", dated possibly 1929. It seems to be a page from a register, with handwritten entries, photographs, and signatures, all on paper and in ink. I’m struck by how… bureaucratic it feels. What can you tell me about this artwork? Curator: It's compelling to consider this page not just as a document, but as a produced object. Think about the labor involved in its creation: the manufacturing of the paper and ink, the printing of the register itself, the photography, and of course, the writing and signatures of all those involved. Each entry represents a life, but also a unit of administrative labor. What kind of power dynamics do you see reflected in these processes? Editor: Power dynamics? Well, it's a "Colonial School," so immediately I think of the power imbalance inherent in colonialism itself. These are records of women being trained, presumably to participate in colonial structures? Curator: Precisely. Consider the “product” of this school – what skills were these women being taught, and to what end? How might the materials used – the very paper and ink – have been connected to colonial economies, to resources extracted from colonized lands? Think about where the raw materials to make the paper or the ink would have come from. Editor: I never really considered that… the material link. So the "artwork," or in this case, the document, is sort of a record of material exploitation as well as of individual lives? Curator: Exactly. The photographs, for example: what kind of resources, labor and technology was necessary to take the pictures and incorporate it into this document? What do they communicate, intentionally or unintentionally, about the relationship between colonizer and colonized? What can the signatures reveal to us as material traces? Editor: I see, it's more than just names. The way they are written is a form of labor. Curator: Yes, and it indicates varying degrees of legibility and control of the means of writing. It all paints a picture of how colonial structures operate through these mundane, material processes. Editor: I’ll never look at an old document the same way again! Curator: I hope so. These objects aren't just records of history; they are products *of* history, embodying power dynamics in their very construction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.