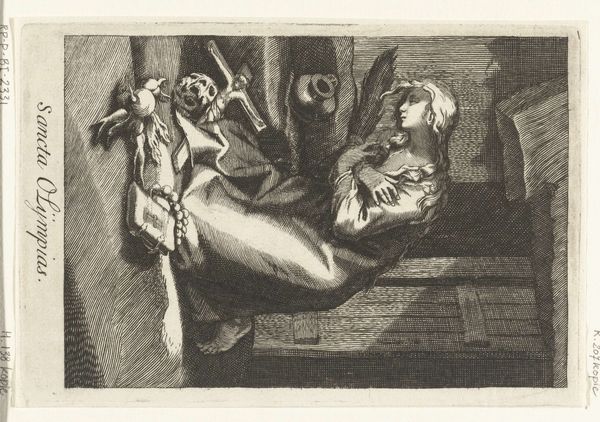

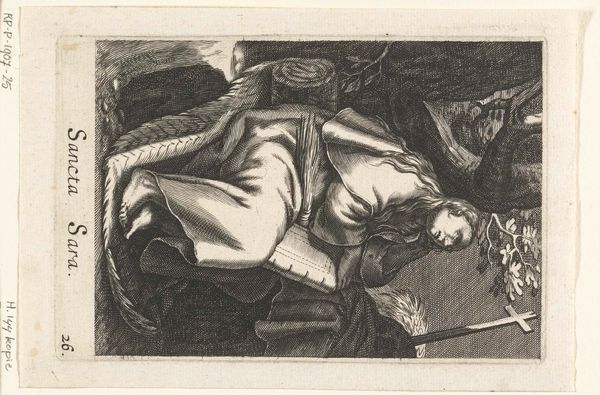

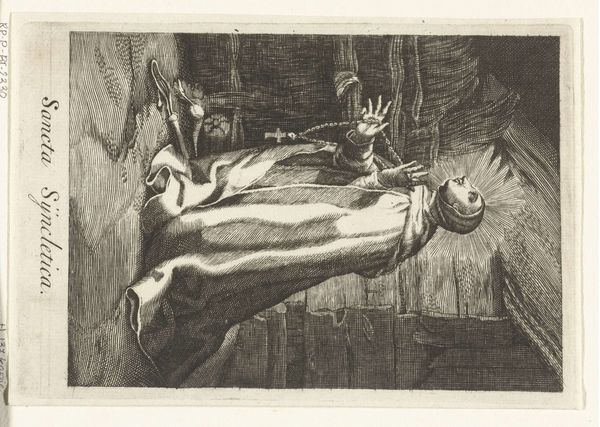

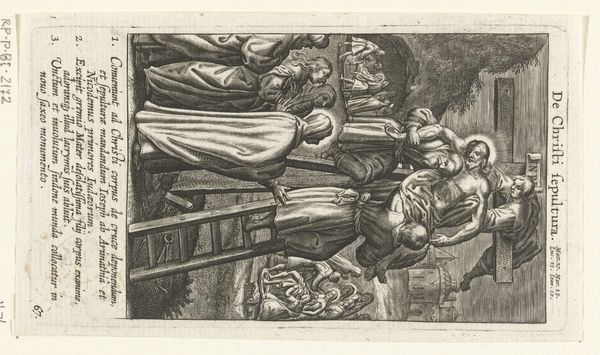

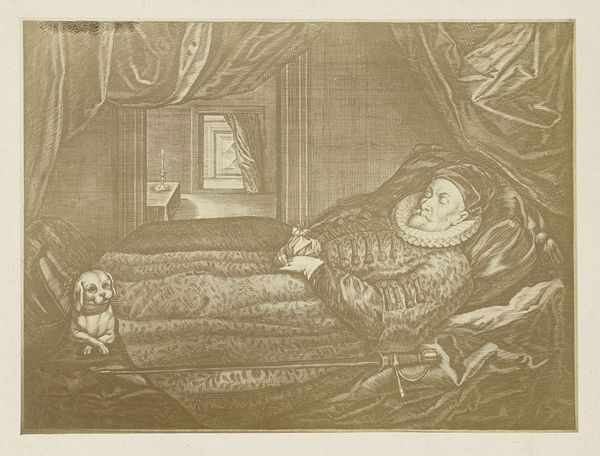

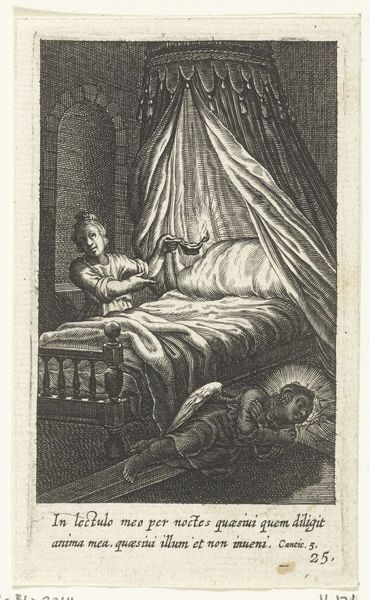

Kind staat voor gordijn waarachter zich een engel verschuilt 1590 - 1624

0:00

0:00

boetiusadamszbolswert

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 56 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's take a closer look at "Kind staat voor gordijn waarachter zich een engel verschuilt," an engraving by Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert, dating from between 1590 and 1624. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The starkness is the first thing that grabs me. The way the lines are so economical, but still create so much drama, this definitely strikes you as an engraving, but that does not diminish its ability to capture the mystical, that feels somehow unsettling too, unsettling but somehow compelling. Curator: Indeed. Bolswert was part of a wider artistic and intellectual environment. Religious prints like this were important for disseminating visual and theological ideas, especially during the Counter-Reformation period. What do you make of that drawn line? Editor: You are right, because there is an angel, of course, behind the drawn drape of, I would venture to say, a drawn, engraved tapestry, but what is remarkable to me is how all this comes to life only by virtue of very precise engraved lines in ink. Curator: Notice the staging, the theatrical curtain. The divine presence is being unveiled for the child. There's definitely a didactic function, instructing on faith and perhaps obedience. But didactic prints were popular, so the public obviously responded to their message. Editor: Yes, but look how reliant it is on this crafted method! Each of these pulls from thread is rendered with care to produce the optical affect in what comes across in some ways more affective in black ink than full baroque color. This piece makes clear how engravings circulated and participated in, and actually became a form of, cultural memory for many common Europeans. Curator: I think this engraving exemplifies how the early modern print media served both artistic expression and social and political purposes. Editor: Absolutely, considering both material execution and function enriches our viewing of this work so profoundly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.