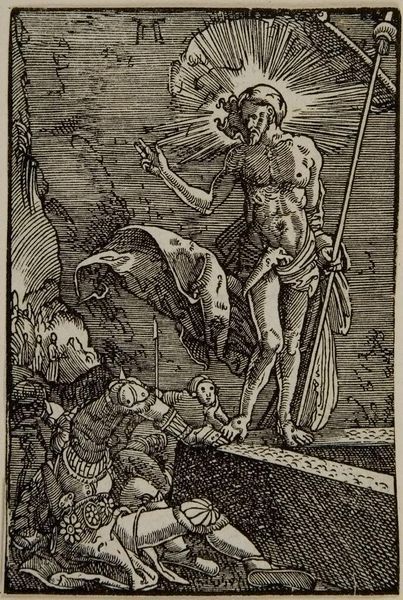

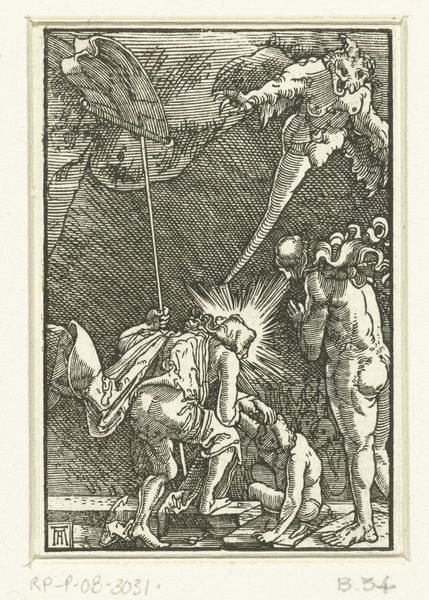

print, woodcut

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 78 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at "The Archangel Michael Slaying a Devil," a woodcut by Hans Springinklee, created sometime between 1500 and 1516. It's currently at the Rijksmuseum. I find the intricate linework striking – a real contrast between the powerful, almost serene Michael and the writhing, reptilian devil. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: It's fascinating to consider this woodcut in the context of the Reformation brewing during Springinklee's time. Images like these weren't just about religious instruction; they were potent visual tools shaping public opinion. Consider the role of Michael as a symbol of righteous authority, of divine intervention against chaos. How might this resonate with the social upheavals and challenges to religious authority of that period? Editor: That’s a great point. So, it's not just a religious scene, but also maybe a commentary on social order and challenges to the church? Curator: Exactly. Think about how the Reformation questioned established power structures. This image, circulating widely as a print, reinforces a specific narrative of divinely sanctioned power crushing dissent, represented by the devil. How might viewers from different social classes have interpreted that symbolism differently, I wonder? Editor: Perhaps the elites would have embraced it as a reinforcement of their authority, while the common people, struggling under that authority, might have found a different meaning. I’m not sure what, though. Curator: Or maybe they found the strength to endure because in the end the devil loses? It’s about faith, resistance, or perhaps resignation to their place within a predetermined social order. Examining such works pushes us to unpack complex power dynamics at play during periods of dramatic change. Editor: I hadn't considered the intersection of religion, social power, and printmaking in this way before. I guess images can be pretty radical! Curator: Indeed. It reminds us that art isn't created in a vacuum but actively shapes and is shaped by its socio-political environment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.