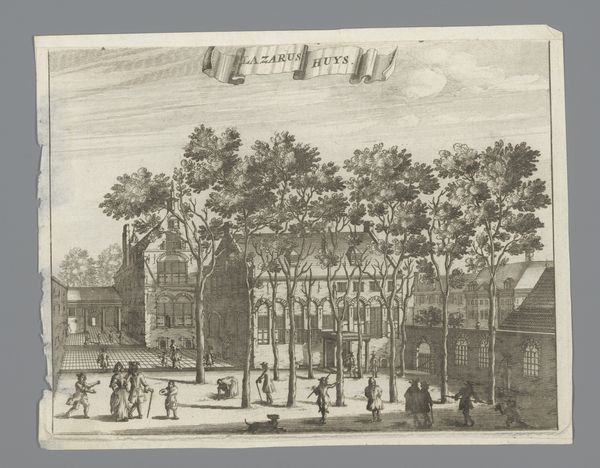

Gezicht op de Waalse Kerk en het Sint-Jorishof te Amsterdam 1663 - 1664

0:00

0:00

jacobvanmeurs

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

ink

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 296 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

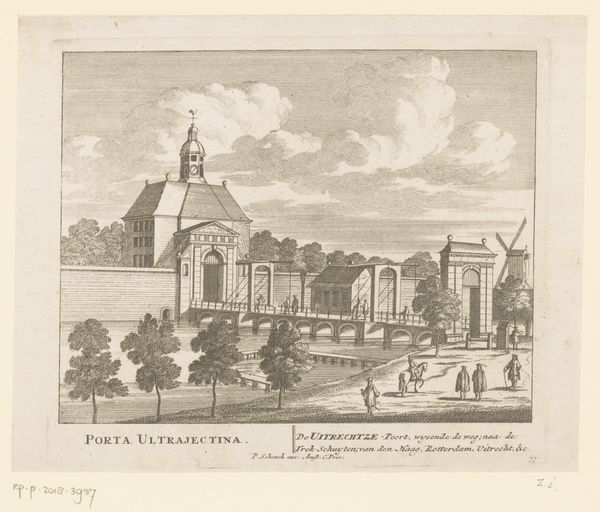

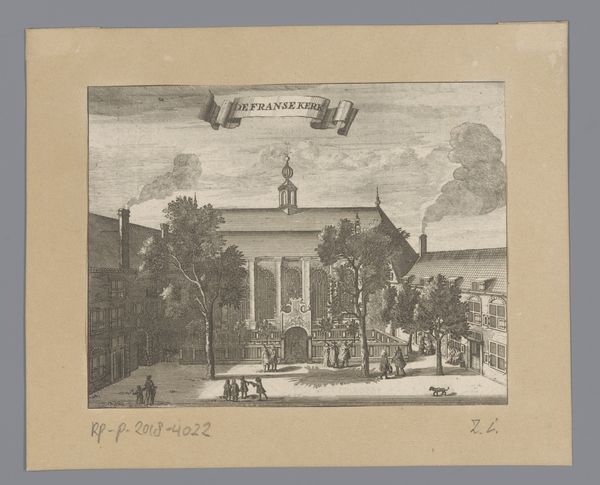

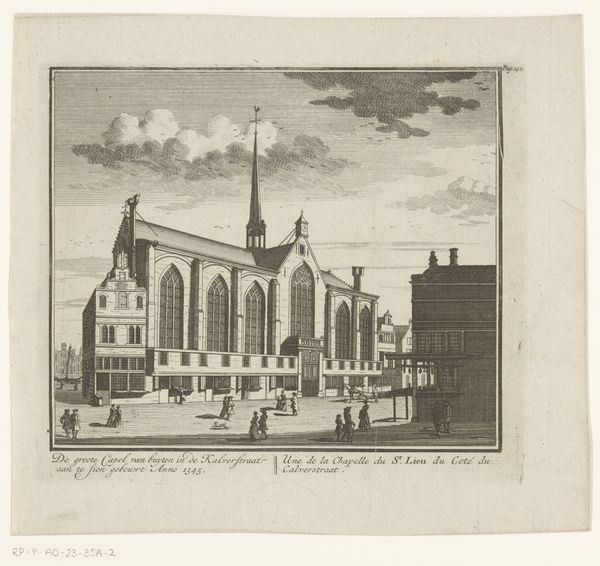

Curator: Here we have an etching by Jacob van Meurs dating from around 1663-1664. The work is entitled, "Gezicht op de Waalse Kerk en het Sint-Jorishof te Amsterdam," or, "View of the Walloon Church and the Sint Jorishof in Amsterdam." Editor: My initial impression is one of detailed serenity, a quiet moment captured in what must have been a bustling urban center. There's a sense of both grandeur and intimacy here. Curator: Indeed. Van Meurs, in this cityscape, offers a look into Amsterdam's urban fabric of the time, focusing particularly on the architectural details and the layout of the locale. The Walloon Church was originally a Roman Catholic chapel. The Sint Jorishof, located next door, provided housing for elderly men. Editor: It is interesting to observe how the artist portrays the people—their clothing, posture, even the slight movements. I would be interested to examine how their presence contributes to, or perhaps contrasts with, the more permanent architectural landscape, and whether we can analyze socio-economic power structures by the depicted scene. Are we seeing simply a factual record or a construction of a specific civic identity? Curator: An important question. The print does portray daily life but likely through the lens of representing the city's Protestant values. Its emphasis on the orderliness and functioning of its social structures sends a very subtle political message, doesn't it? This view provides information about Amsterdam's evolution as a tolerant society. The presence of the Walloon Church—originally French speaking—in itself is quite remarkable given Amsterdam's religious history. Editor: Yes, these carefully arranged figures and buildings provide subtle commentary about civic life, as well as tolerance, specifically regarding the situation of the Walloons. What's striking is that van Meurs situates a religious institution in the daily activity of ordinary people, not through sermons or acts of religious dedication, but mundane activity and its quotidian spaces. How do we read the quiet of the courtyard in terms of power, order and its negotiation with dissent? Curator: Fascinating food for thought. I am particularly intrigued by what the inclusion of those barely discernible figures tells us about 17th-century views on personhood and social hierarchies. Editor: Agreed. Each etched line here bears the weight of so many interwoven socio-political and personal histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.