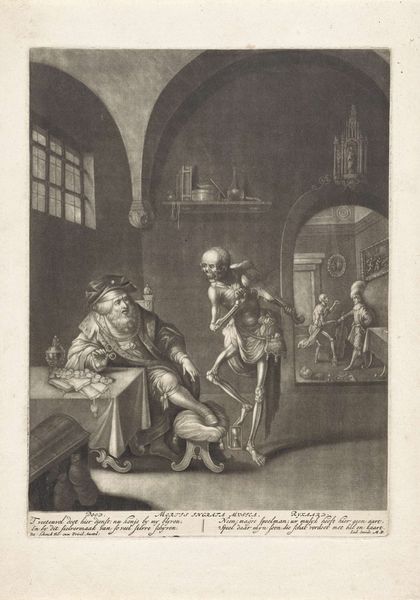

drawing, etching, ink

#

portrait

#

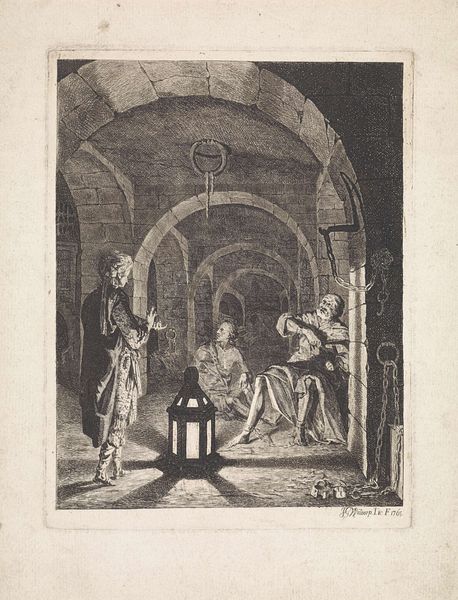

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

baroque

#

etching

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

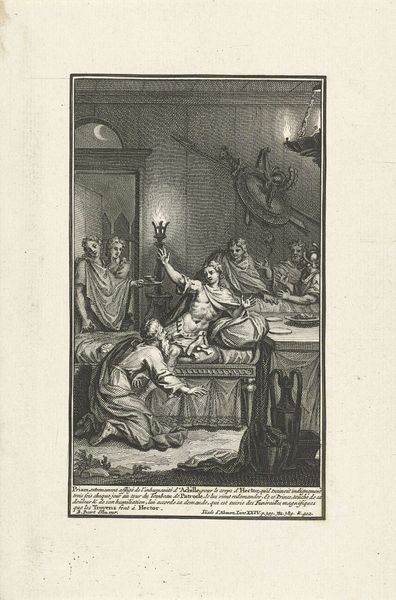

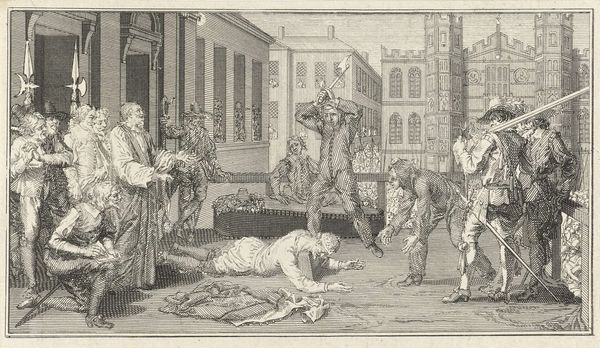

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

academic-art

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

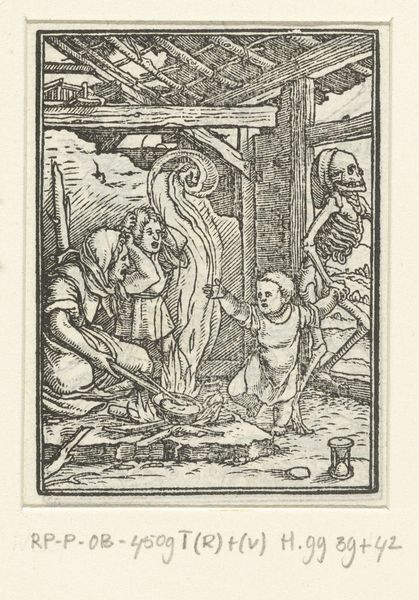

Curator: This piece is titled “Anatomie en Natuurgeschiedenis,” or Anatomy and Natural History, an etching in ink by Bernard Picart, dating sometime between 1683 and 1733. It's quite a scene! Editor: It's rather macabre, isn't it? And yet there’s this playfulness with the cherubs, that tempers the harshness. It makes me wonder, who exactly was the intended audience? Was this supposed to be shocking, informative, or even humorous? Curator: Well, etchings like these were common in academic circles. They served as illustrations in books, scientific publications, and even private collections of scholars. So, in the context of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, a piece like this would’ve spoken to a culture deeply fascinated by scientific exploration and classification. The depiction of putti engages classical allegories, framing even death as an integral facet of cyclical life. Editor: Cyclical, yes, but still imbued with a strange, colonial-era scientific gaze. You've got these chubby, winged cherubs dissecting what appears to be a cadaver on a table while animal skeletons dangle above them. A stark memento mori— mortality looms everywhere you look. But this "Anatomy and Natural History" feels inherently hierarchical; Western European ideas about natural science dominate the frame. The "nature" here, isn’t nature itself. Instead it is an extracted, examined, objectified version. Curator: Absolutely, and that's a reflection of the burgeoning scientific societies of the period, and how new forms of visuality shaped new epistemologies. Look at how the artist has rendered the skeletal structure – meticulous and detailed. He’s showcasing the order of nature. He’s documenting a particular brand of scientific rationalism through visual means. And this print very likely circulated within elite networks that patronized institutions like the museum that housed this gallery and the academy itself. Editor: Precisely. We cannot remove our current understandings of institutional critique and its impact on contemporary knowledge systems from interpreting Picart’s etching. We can appreciate the skill while challenging the perspectives it embodies, examining how scientific institutions were being visualized as domains of exploration and sites of social authority. The artist reproduces this vision even as he portrays death and rebirth. Curator: Indeed. Thinking about its historical context enriches our viewing experience. These seemingly strange arrangements were not just morbid curiosities. Editor: No, they represent something far more telling about what those centuries deemed “progress,” the ongoing legacy of how humans understand and visualize "nature".

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.