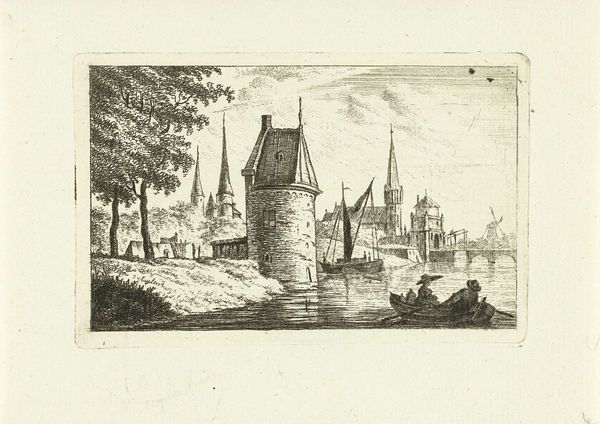

etching

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

realism

Dimensions: height 131 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Rivierlandschap," or "River Landscape," an etching made by Hermanus Welsink in 1864. Editor: It's so delicate! The scene feels still, like a memory fading into the past. You can almost smell the river. The fineness of the etched lines, I wonder what that required in terms of skill and specialized equipment. Curator: The etching process involves using acid to bite into a metal plate, allowing for very fine, detailed lines like we see here. Think about the etcher’s workshop: the smells of acid and ink, the specialized tools, the collaboration or isolation of the artist. How these working conditions informed the finished artwork. Editor: Exactly! And how the choice of etching itself – a process that allowed for multiple reproductions – made this kind of landscape imagery accessible to a broader public beyond traditional painting audiences. Before photography became widespread, etchings and engravings were crucial in shaping public perception. I am curious, how was Welsink received back then? Curator: He was among those contributing to a growing market for prints. Landscape prints offered an ideal escape to the burgeoning middle class, hungry for signs of Dutch national pride. Think about how Welsink chose a tranquil river scene, a motif that reflected back contemporary ideas of the rural idyll. Editor: A calculated projection! You're right; the subject matter catered to particular social aspirations and artistic traditions. The placement of the church spire in the distance also nods to established landscape conventions while subtly reinforcing social structures. So much information conveyed in the seemingly simple composition. Curator: Welsink definitely engages in some contemporary image management! But also consider the materials he would be choosing. Papers can vary widely in fiber content and acidity, affecting the longevity and look of the finished work. His choice to work small might imply a more affordable avenue. Editor: Good point! And considering the political climate of the time, with increasing industrialization, idyllic scenes like this served a vital function – promoting values, reaffirming collective identities through curated depictions of 'nature' as distinct from, yet in proximity to, a developing city landscape. The market decides. Curator: It also challenges this view: even what looks at first like untouched beauty involves material processes and skillful construction, influenced by historical forces. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing beyond the surface reveals the layers of social, cultural, and political negotiation at play. It transforms a quiet river scene into a document rich in art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.