photography

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

plant

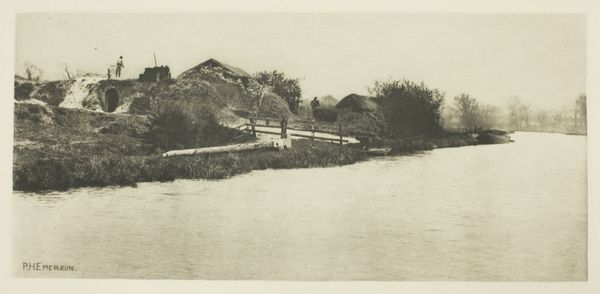

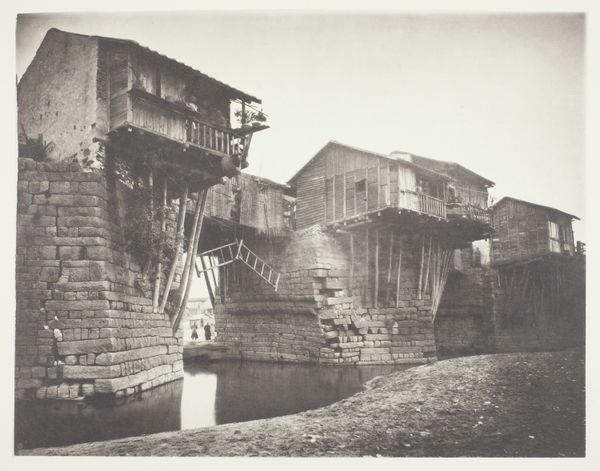

Dimensions: height 297 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

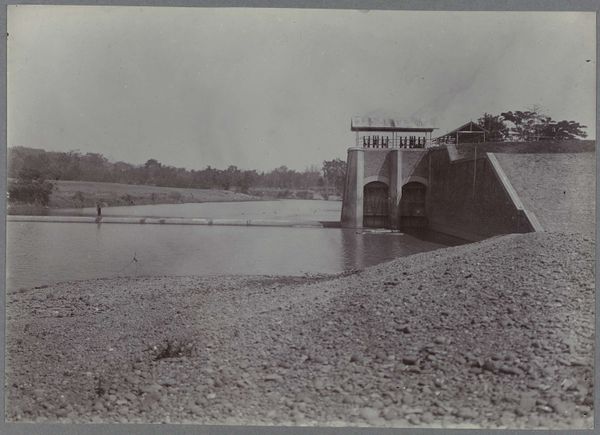

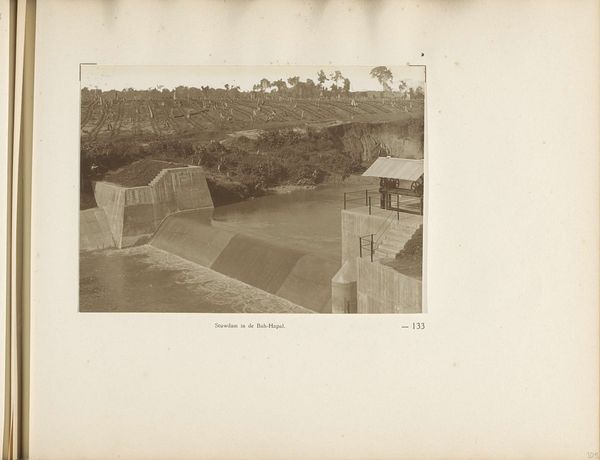

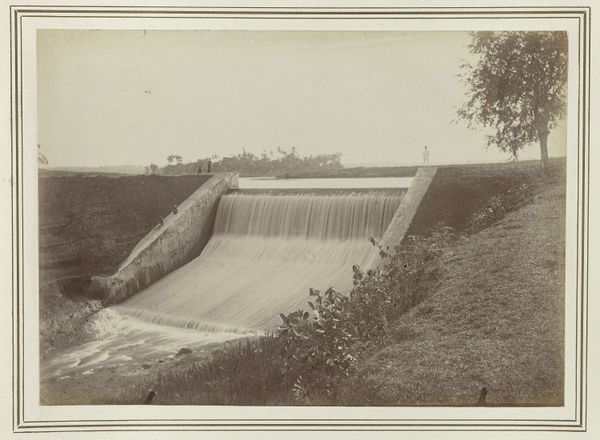

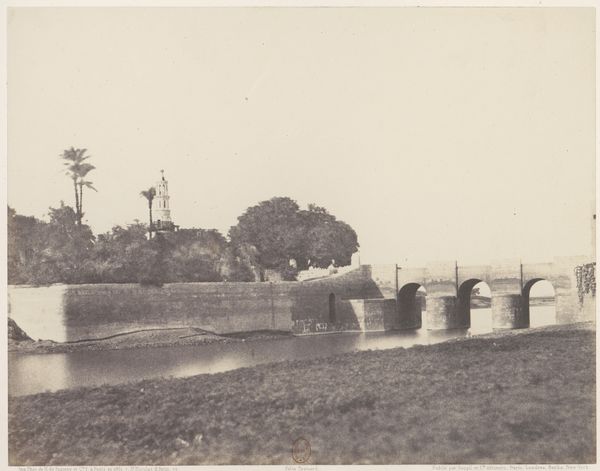

Editor: Here we have an undated photograph from sometime between 1925 and 1930, titled "Sluizen in de kali Konto bij suikerfabriek Goedo te Djombang op Java," which I believe translates to "Locks in the Kali Konto near the Goedo sugar factory in Jombang, Java". It gives me a feeling of being far removed from a natural landscape – something constructed, maybe a little unsettling? What strikes you most about it? Curator: That feeling of estrangement is key. What we see is not simply a landscape, but a colonial landscape, actively engineered to serve the sugar industry. Look at the harsh lines of the locks juxtaposed with the softer, tropical foliage. The photo speaks volumes about resource extraction and the subjugation of the environment, and, by extension, the local population, in service of a global commodity. How does the visual composition reinforce this idea for you? Editor: Well, the structure seems to dominate the composition. Even the little building looks severe. The water is being controlled. Does the very act of photographing this scene have colonial undertones too? Curator: Absolutely. Photography, especially in this era, was a tool of empire. Images like this one reinforced the idea of the colonizers' ability to tame and exploit the landscape. What might seem like a neutral document is actually deeply embedded in power dynamics. This sugar factory existed within a complex web of economic and political control. What can this image tell us about that exploitation? Editor: I hadn't really thought of it that way. It seems obvious now that you point it out, but I saw water and architecture first. Knowing that history gives the picture a whole new disturbing depth. Curator: Exactly. Art history is never separate from social history. Reflecting on colonial legacies is essential when engaging with images like this. It reminds us to always question what’s presented and whose story is being told, and at whose expense.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.