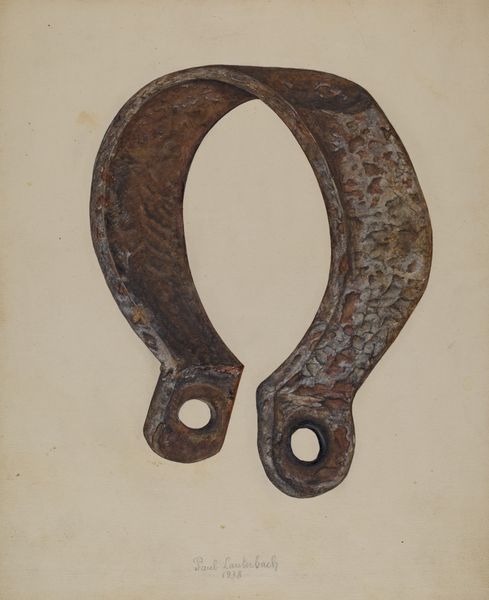

drawing, painting, watercolor

drawing

painting

watercolor

modernism

realism

Dimensions: overall: 35.5 x 24.7 cm (14 x 9 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

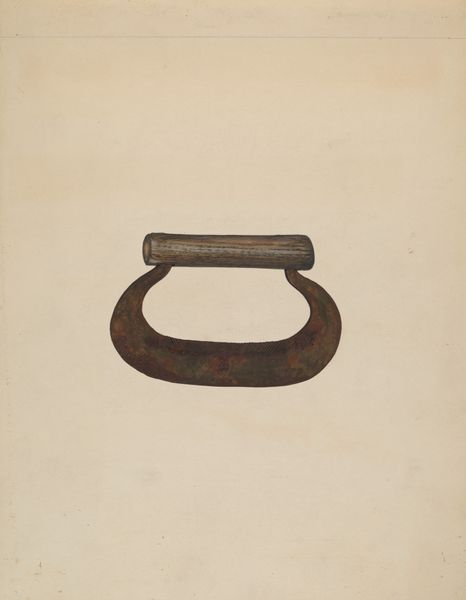

Curator: Well, here we have William Hoffman's "Hoe Blade," circa 1941. It's a striking example of his work in watercolor and drawing. Editor: My first impression is one of quiet dignity. It’s an everyday object, isolated against this warm beige background, almost monumental. Curator: Exactly. The visual isolation allows us to really focus on the object itself – the soft gradients of color rendering a sense of three-dimensionality that speaks volumes despite the object’s stillness. How does the texture work for you? Editor: There is something powerfully evocative in its depiction here. It's more than just a farm tool; it represents a specific class in society—those tied to the land through hard manual labor, the ordinary folks, if you will. This isn't simply about showing off technical prowess; it is deeply sociopolitical. Curator: A valid reading. Yet I'd add it goes beyond any immediate historical commentary. Hoffman's meticulous construction—the interplay of curves in the upper handle against the sharp edges of the blade—imbues this ordinary tool with an abstract sculptural presence. One may argue he almost depersonalizes it, removing a degree of connection with social realities of the day. Editor: I am less certain that Hoffman distances himself, perhaps he’s attempting to honor a segment of the population with his close, even monumental, examination of their everyday labor. Did Hoffman specifically acknowledge a commitment to social commentary? Curator: Historical records provide minimal explicit statements of Hoffman’s explicit commitment. Instead we could consider a pure, direct realism that forces us to examine beauty in unlikely, utilitarian forms. The work resonates by showcasing its elemental shape. Editor: Perhaps, but art rarely exists within a vacuum, especially depictions of objects linked so strongly to rural communities, the rise of regionalism, and the American scene painting movements during the Depression. These factors inherently add complexity. Curator: Regardless, I am thankful we can analyze how Hoffman allows the mundane to speak volumes about structure and composition. It showcases how form becomes just as important, perhaps even supersedes historical intent. Editor: Agreed, our considerations ultimately deepen the visitor’s engagement with the complexities inherent to interpreting art, beyond the purely visible.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.