photogram, photography

#

photogram

#

photography

#

geometric

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 312 mm, width 242 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

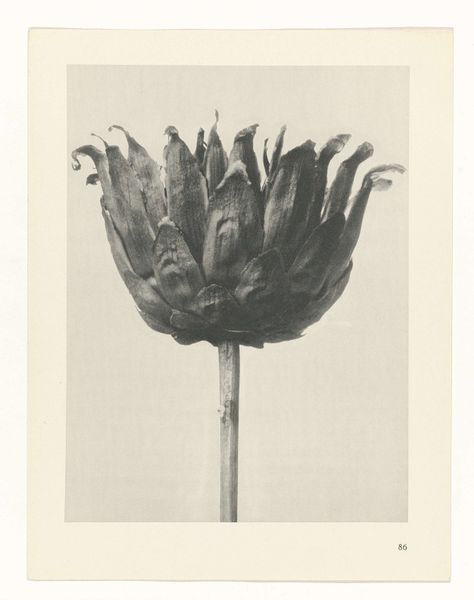

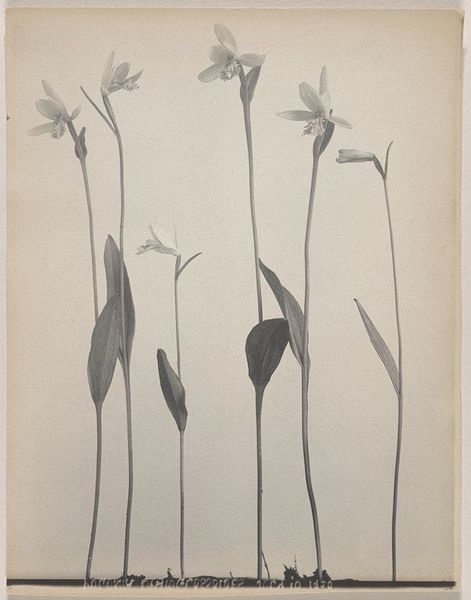

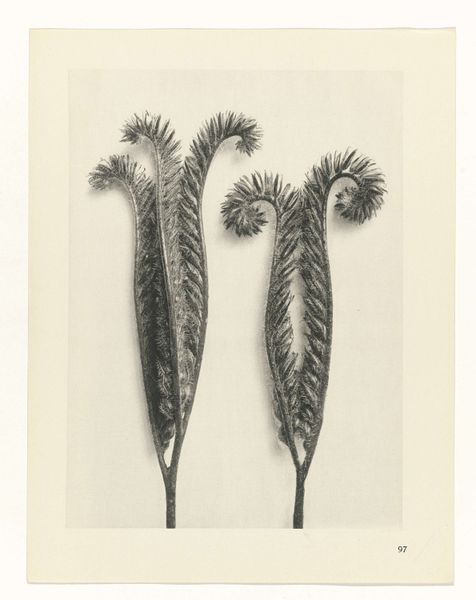

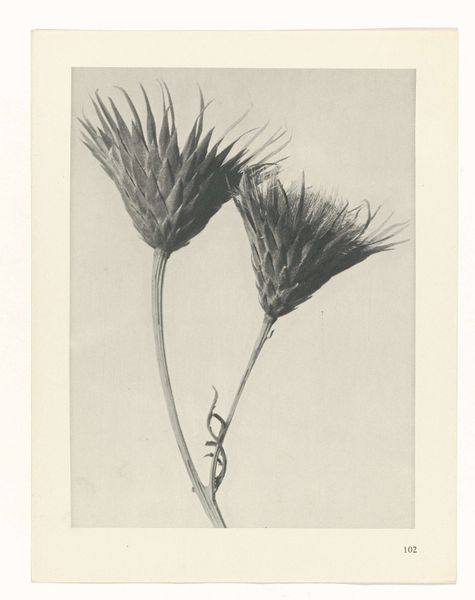

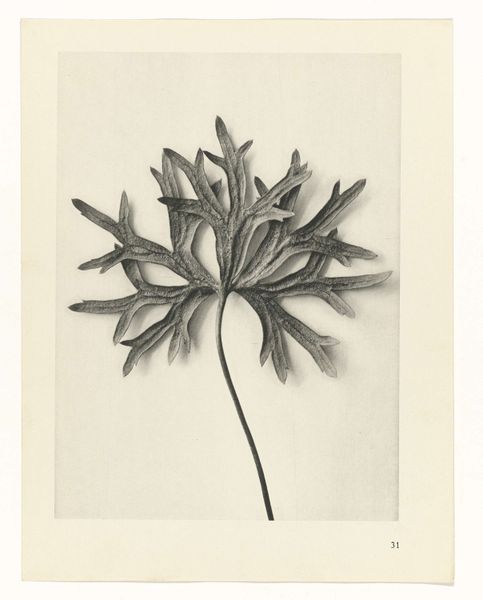

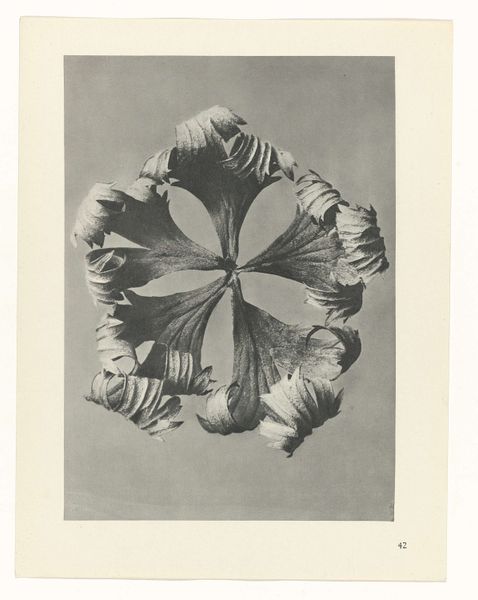

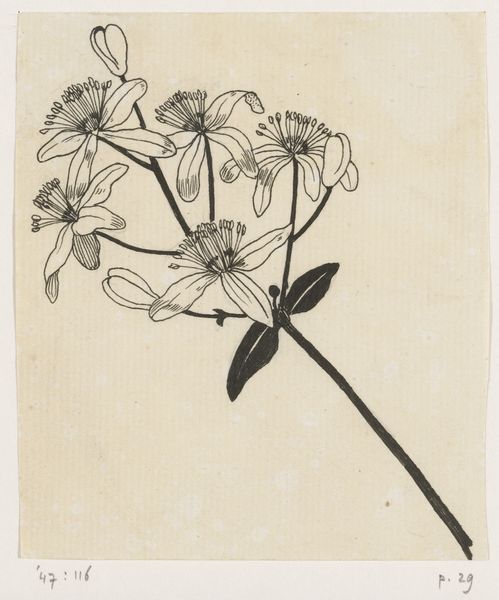

Curator: Looking at Karl Blossfeldt’s “Plant Study,” taken around 1928, what strikes you initially about this photogram? Editor: It feels almost architectural, like some Art Deco skyscraper rendered in sepia tones. Stark, geometric, but with a biological heart. Curator: That’s interesting. Blossfeldt’s work, especially these close-up botanical photographs, played a significant role in the New Objectivity movement in Germany. The goal was to reveal the inherent structure and formal elegance in nature, often unseen by the naked eye. It's about uncovering fundamental geometric forms. Editor: And there’s something undeniably radical about turning nature into, well, almost propaganda for industrial design. We’re using organic forms to validate the machine aesthetic. How does that tie into the socio-political climate of the time? Curator: The Bauhaus movement, with its focus on functionalism and the unity of art, craft, and technology, was highly influential. Blossfeldt's images were exhibited in galleries frequented by architects and designers. These forms mirrored the new urban landscape of Germany and a desire for simplification after World War I. This approach rejected the ornamental in favor of pure, unadorned design. Editor: Right, simplification born out of the trauma and hyperinflation, even collapse. But looking closer, I feel tension between celebrating inherent natural beauty and the potential for appropriation. Were Blossfeldt's intentions simply artistic, or were they inherently political? I keep thinking about how images of natural perfection were later exploited in propaganda. Curator: That’s a crucial point to consider. Blossfeldt saw himself primarily as an educator, using these photographs as teaching aids. The photogram’s reproducibility lends it democratic quality. These plant portraits were meant to highlight nature’s capacity to generate patterns, to invite deeper understanding. Its relationship to later ideological appropriations opens up a complicated ethical question. Editor: Absolutely. It also feels important that these images, celebrated at the time, may now offer insights into biodiversity and climate change if recontextualized as archival documentation. Curator: Thank you. Those tensions highlight the continuous nature of meaning-making as cultural context evolves. Editor: Yes, and reminds us that, despite seeming objective, art remains entrenched in a complex interplay between the intentions, perceptions, and politics that evolve across generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.