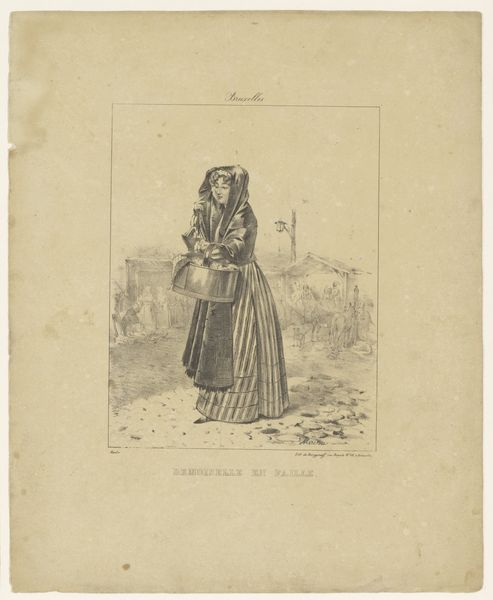

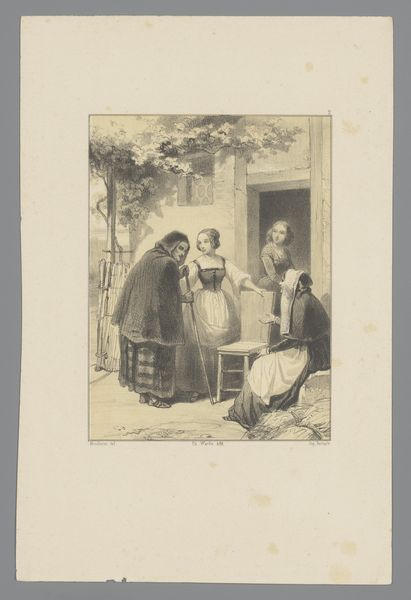

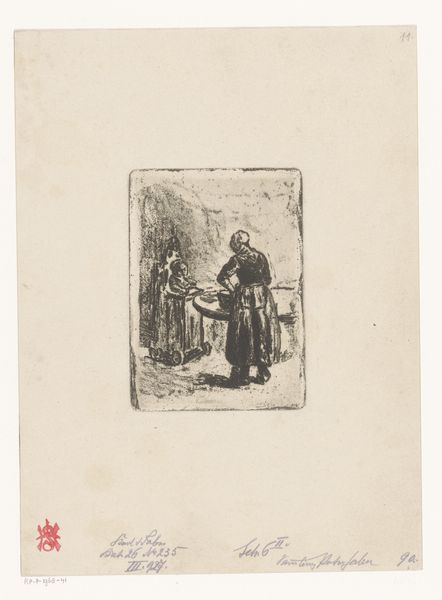

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 347 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Bloemenverkoopster op een plein te Brussel," or "Flower seller on a square in Brussels," a drawing and engraving made sometime between 1825 and 1835 by Jean-Baptiste Madou. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum collection. What’s your immediate impression? Editor: Stark. It’s that almost photographic clarity, rendered through detailed print work on the cobbled streets and the woman’s attire, which suggests the weight and texture of fabric, of the flowers she carries. The material reality is unavoidable. Curator: Absolutely. Madou’s work frequently depicted scenes from everyday life in Brussels. This piece reflects the rise of genre painting in the Romantic era, celebrating ordinary people in public spaces. What’s interesting to me is the politics of depiction. Consider how images like these were consumed, and what kind of cultural ideas they bolstered about urban life. Editor: Right, these prints were commodities in themselves. Engravings enabled broader consumption; a burgeoning middle class eager to consume images that mirrored—and possibly validated—their own burgeoning social status. The details tell us a lot about class distinction at that time—the seller’s clothes and headdress versus the wealthier figures lingering in the background near what appears to be a royal palace. Curator: I agree, and Madou had close ties with the royal family. These weren't straightforward documents. Rather, his prints participated in the cultural constructions of identity. This is more than just recording the ‘real’. The woman's elegant composure, the meticulous portrayal of architecture—they contribute to a carefully structured narrative. Editor: What I keep circling back to is the artist’s labor—the number of hours involved to create those fine lines. The work mirrors the labor of the flower seller herself. This print elevates what would be considered, historically, “low” subject matter through skilled craft and the material realities of printmaking. Curator: And think about how many impressions were made of this image. It reflects an increasingly image-based culture. Consider that against the broader socio-political upheavals. Editor: Exactly. Looking at art this way puts what’s being shown, who it was shown to, and how it was crafted all in context. I come away appreciating not just its artistry but its function as an object of labor. Curator: I am left to consider this artwork’s role in defining and circulating ideas about labor, urban space, and Belgian identity during a pivotal era of social transformation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.