photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

realism

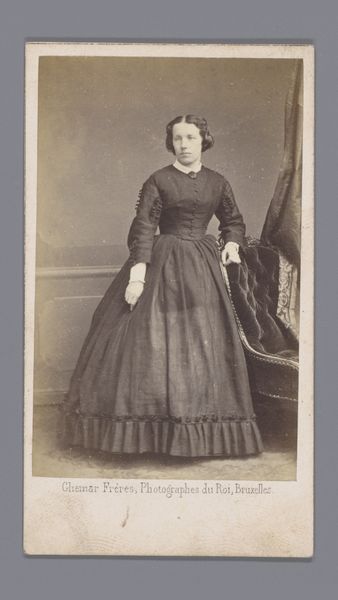

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a gelatin silver print, "Portret van Mme. Haverals," created sometime between 1863 and 1880 by Dechamps et Cie. It's a fairly straightforward portrait, but something about the woman's direct gaze makes me wonder what her life was like. What's your interpretation? Curator: What strikes me is how this photograph participated in the democratizing of portraiture. Prior to photography, portraits were the domain of the wealthy, reinforcing social hierarchies. Photographic studios like Dechamps & Cie, especially in urban centers like Brussels, offered access to a broader segment of the middle class. Editor: So, owning a photograph like this one signaled something about a person's social standing? Curator: Precisely! Think about the sitter’s clothing—the elaborate skirt, the ruffled collar—and the staged setting with the balustrade. These were carefully constructed elements, meant to project a certain image of respectability and social awareness. This isn’t just a picture; it's a carefully curated performance of identity for public consumption. Do you notice the relative formality compared to, say, family snapshots of today? Editor: Absolutely, it's a world away from Instagram! So it’s interesting to think of this portrait not just as an individual likeness, but also as a social artifact. Curator: Exactly. Understanding the historical context helps us to understand how even seemingly simple images play a part in a bigger societal picture, especially concerning who gets represented and how. Editor: I never thought about portraiture that way before. Now, looking at the image, I’m struck by how deliberate and constructed the image is. Curator: It’s rewarding to uncover the hidden social narratives embedded in these seemingly straightforward images, isn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.