print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

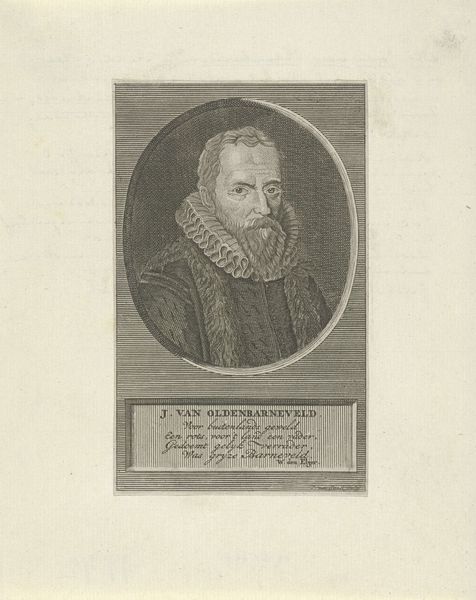

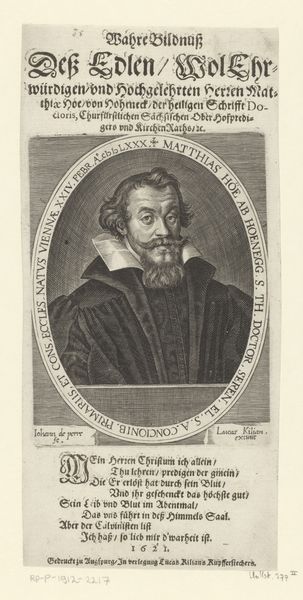

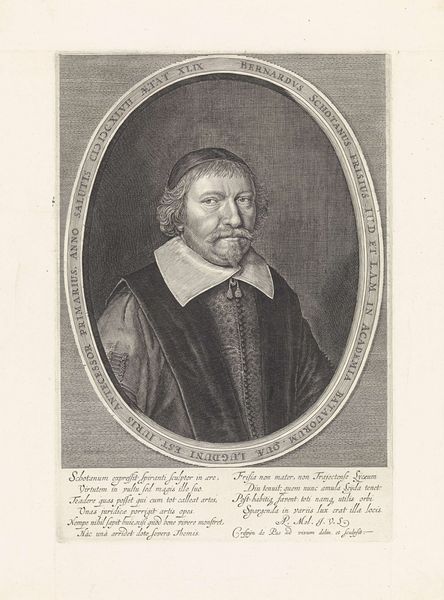

Curator: Well, hello there! I'm just lost in the intriguing gaze of Matthias Pasor. Steven van Lamsweerde etched this portrait back in 1654, using an engraving technique. Something about the delicacy of the lines gets me every time. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The immediate impression is...contained. Look at the oval frame, the formal attire, even the restrained color palette dictated by the print medium. There's a clear message here about power and status in 17th century Dutch society, though I imagine the subject may not be well-known to today's viewer. Curator: He definitely has this very...scholarly air about him, doesn't he? You can practically smell the ink and old books! And the way Lamsweerde captured the light in his eyes gives Pasor a certain twinkle of wisdom... or perhaps just mischievousness. It is easy to admire such an obviously learned gentleman. Editor: Mmm, a learned gentleman of the 17th century, embedded within a context of religious and intellectual reform but also significant socio-economic stratification. He looks the part of an established academic, I'll grant you that, but I think we should question this portrayal of inherent virtue. This portrait flattens the identities and labor of those excluded. Curator: You always bring such important points to the conversation, it’s great! Looking at it technically, Lamsweerde's skill in creating depth with simple lines is pretty impressive. It's almost photorealistic despite being an engraving, a fascinating exercise in transforming a 3-D persona into a 2-D surface. The way that tiny lines define his face! Editor: Precisely. The technical skill is undeniable, and contributes directly to the illusion of Pasor’s importance. But to my mind, that craftsmanship serves to elevate an elite class. How might other Dutch people at that time, especially those disenfranchised by religion, class and/or gender, perceive this portrait of a privileged member of society? Curator: What an excellent, sobering question. I suppose that it can only remind us to look closer and question the apparent truth presented in any portrait, especially those so old, and always question. Well, thank you! Editor: It goes both ways—thinking about portraits this way offers tools of historical examination and personal resistance to ongoing oppressive norms. And who knows what Pasor, or van Lamsweerde, might think of that?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.