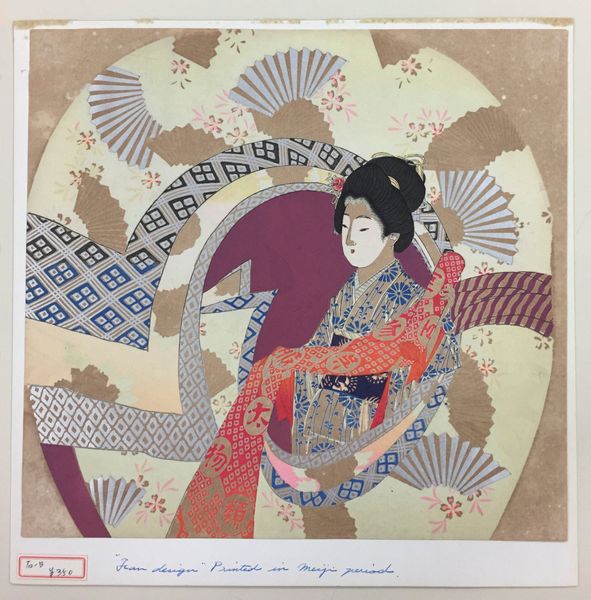

Dimensions: 9 1/4 × 9 13/16 in. (23.5 × 24.92 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

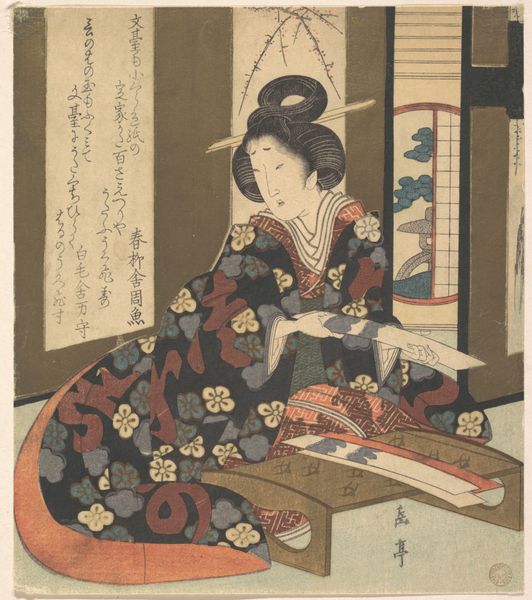

Curator: This serene woodblock print, "No. 22" by Otake Etsudō, completed around 1901, presents a fascinating glimpse into the ukiyo-e tradition. It's part of the collection here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What's your initial reaction? Editor: My first thought is how contemplative and restrained it feels. There's a quiet intimacy. The palette is muted, yet the details on the kimonos create subtle visual drama. It’s not a boisterous image; it’s very internal. Curator: I agree. It epitomizes the concept of "miyabi," that Heian-era courtly refinement. The subject, most likely a courtesan, is portrayed not with overt sensuality, but with understated elegance. The patterns on the kimonos – floral motifs, geometric designs – all speak to specific cultural values and aspirations. Notice, for example, how the hanging kimonos are meticulously arranged, almost like a symbolic backdrop to her inner world. Editor: Right, there's almost a staged quality. It’s fascinating to consider how these prints were circulated—affordable art for the masses. They gave access to the world of the courtesans and the elite, effectively shaping social desires and perhaps solidifying particular gender roles. Was this meant as a celebration or a commentary? Curator: That’s precisely the debate! Ukiyo-e served multiple functions. It could be celebratory, idealizing the pleasures of urban life, yet at other times, artists offered veiled critiques of social norms. Look at her pose – kneeling formally, almost as if presenting the kimono to the viewer. This could be read as both a display of beauty and an acknowledgment of her position within society. The print itself, being a lithograph, signifies a kind of reproducibility, democratizing the image, making it available outside court circles. Editor: And this act of repetition also plays a key role in how we view symbols over time. When visual representations like these are perpetually presented and consumed, doesn’t it create a shared understanding, embedding cultural codes that persist in the collective memory? The image takes on a power of its own, beyond any single individual’s interpretation. Curator: Exactly. In that respect, these seemingly simple portraits act as time capsules. They remind us that our contemporary ideas about gender, beauty, and status are shaped by a complex historical visual language, layered over generations. Editor: A compelling intersection of personal contemplation and social inscription, made indelible through craft. It speaks volumes about what we find precious, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.