#

tree

#

impressionist

#

abstract expressionism

#

sky

#

abstract painting

#

impressionist painting style

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

fluid art

#

acrylic on canvas

#

plant

#

seascape

#

natural-landscape

#

nature

#

natural environment

#

expressionist

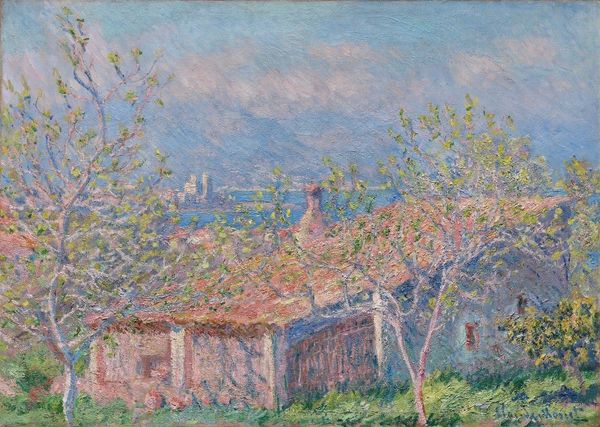

Copyright: Public domain

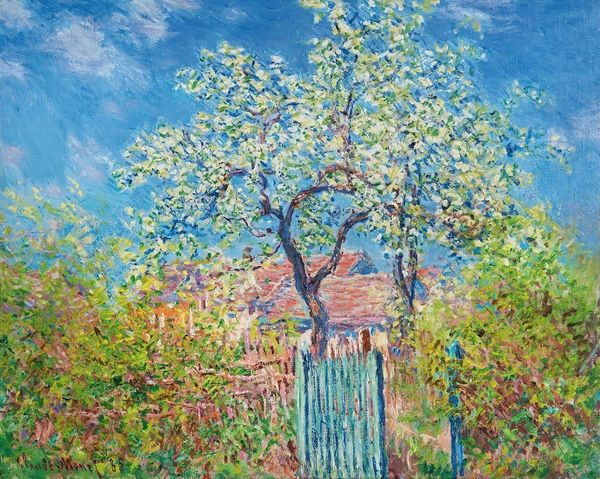

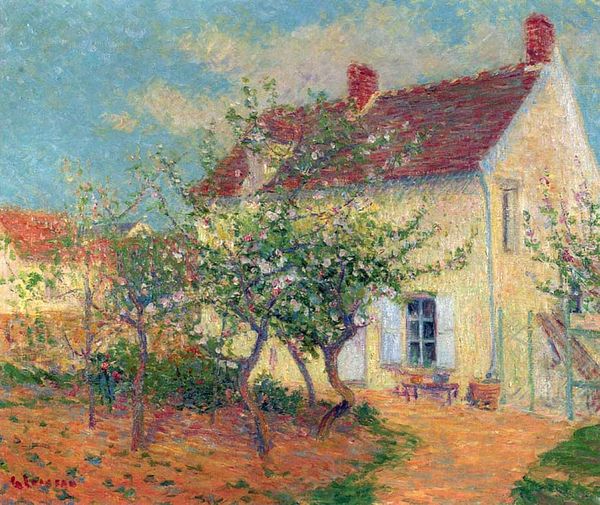

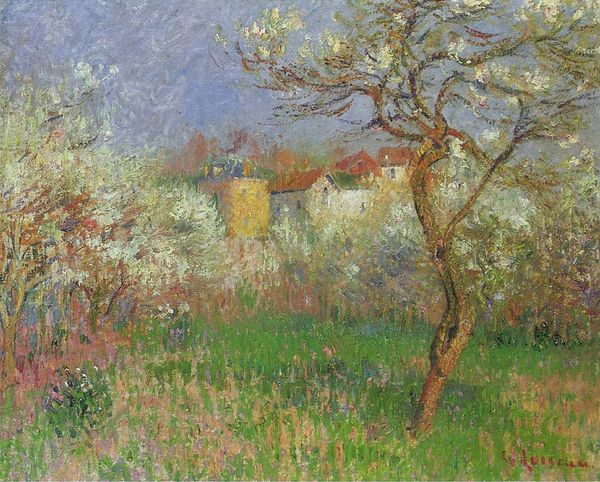

Curator: This piece is Claude Monet's "Springtime at Giverny," created in 1886. What do you see in it? Editor: I see a memory—a feeling of dappled sunlight and soft growth, filtered through an intensely personal lens. The color is riotous. Curator: Absolutely, Monet’s works offer fertile ground to explore identity and representation, and his Giverny period speaks volumes. Think about it: what does choosing to depict his own carefully curated natural landscape say about the artist’s self-fashioning and position within the cultural landscape of 19th-century France? Editor: I am intrigued by the prevalence of that vibrant red in the home’s rooftop; in juxtaposition with the delicate whites and blues of the blossoming trees, that hue is an anchor for my eye and possibly the painter's consciousness, evoking a specific place in both reality and imagination. What symbols were potent for Monet at that stage in his personal history? Curator: Well, Giverny marked a significant chapter for him, signalling newfound financial stability and artistic recognition. That’s something important to keep in mind when considering how nature serves not only as inspiration for a painter, but also as an instrument in class mobility. Did these spaces allow room for greater agency among artists, who might reimagine themselves? Editor: He transformed external experiences into subjective and symbolic forms. Every bloom feels like a coded letter in Monet's language. He repeats motifs that seem almost dreamlike as they appear over time in similar renditions of these settings; this repetition gives us permission to dive even more deeply into an analysis that isn't just about art but also history, culture, psychology and more. Curator: Exactly! We must not disconnect aesthetic expression from its socio-historical roots; consider for example how depictions of idyllic landscapes played into complex colonial fantasies in this same era! It becomes so obvious how seemingly simple visual impressions serve bigger purposes than just 'beauty.' Editor: Yes, it shows that artists shape their self-perceptions by how they choose particular environments; meanwhile their symbols grow along familiar yet unpredictable paths of their interior terrain--and for us as beholders too--that is beautiful to see. Curator: Thinking through those historical tensions and Monet's agency allows us richer understanding about these masterpieces. Editor: Precisely – letting our gaze and contemplation follow pathways towards personal associations in memory lets new symbolic resonances grow as naturally, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.