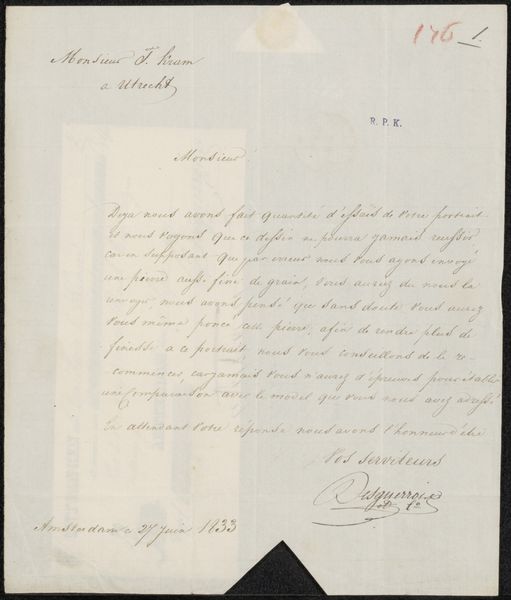

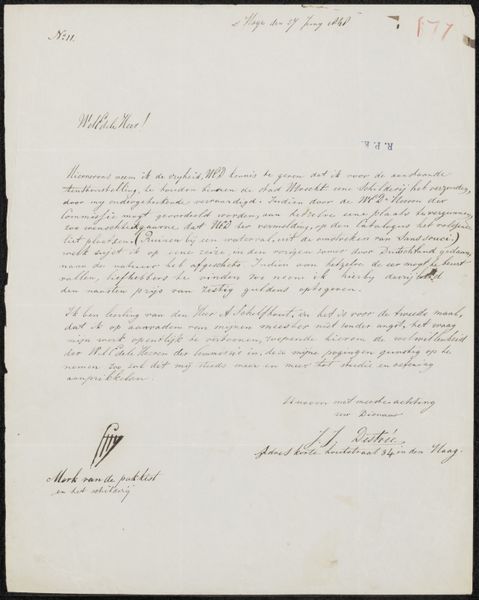

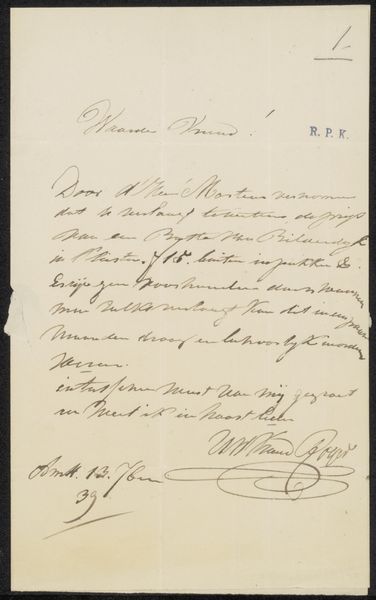

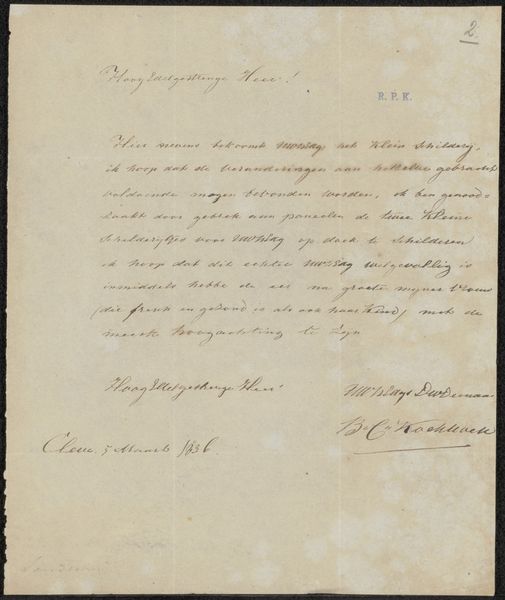

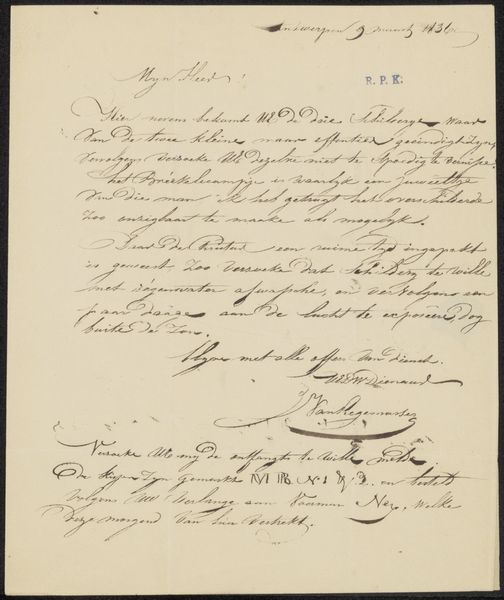

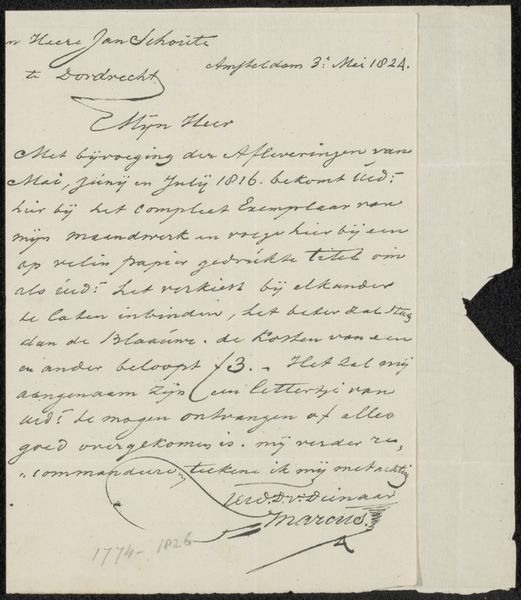

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

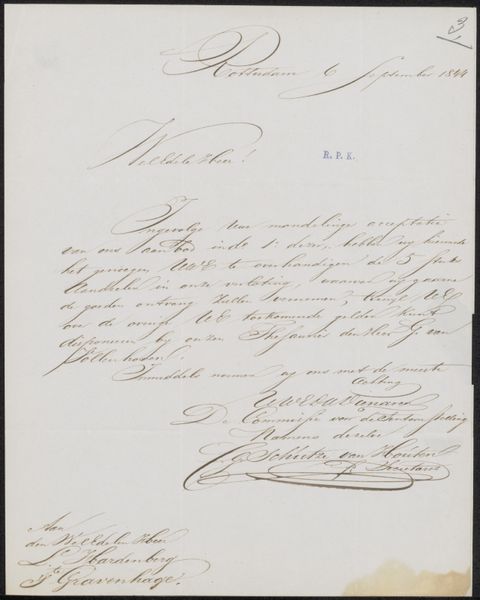

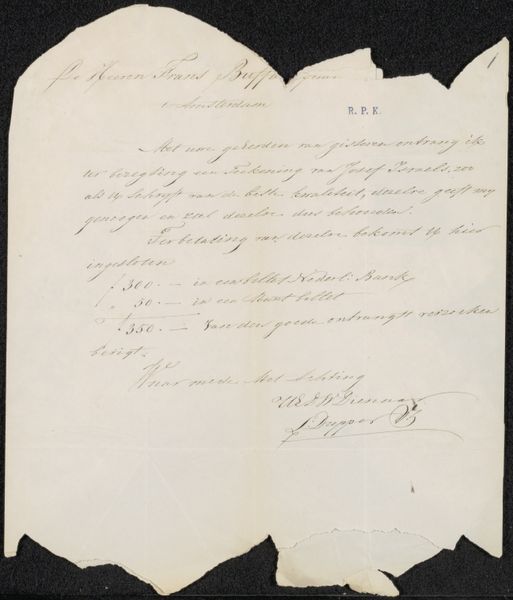

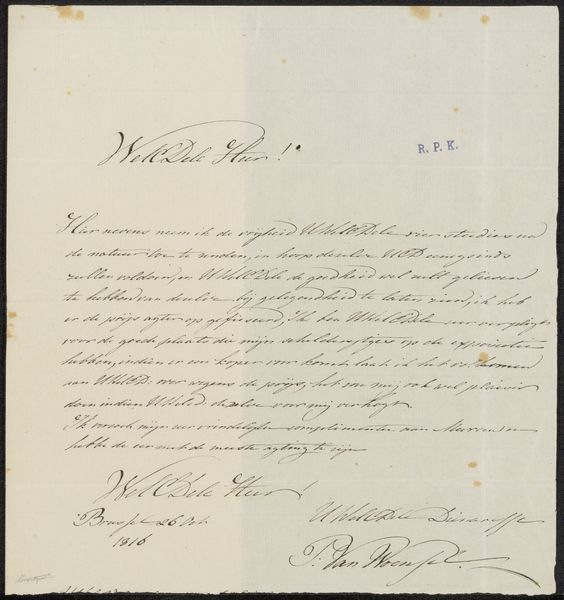

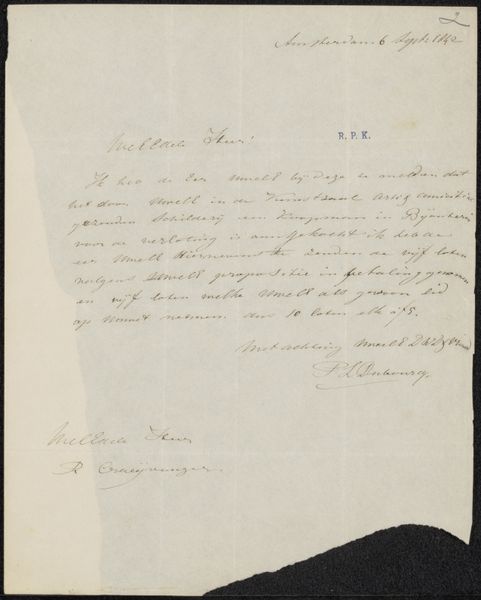

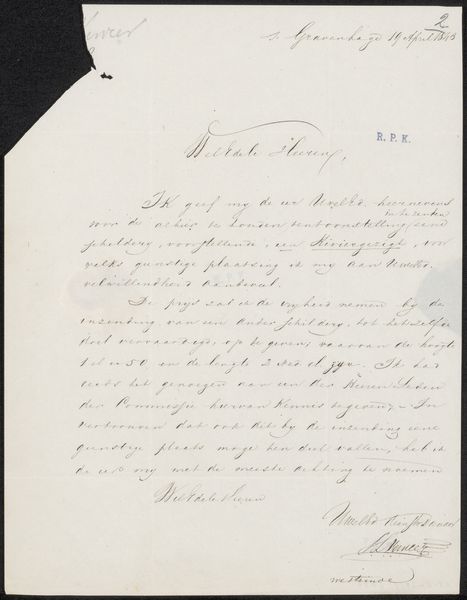

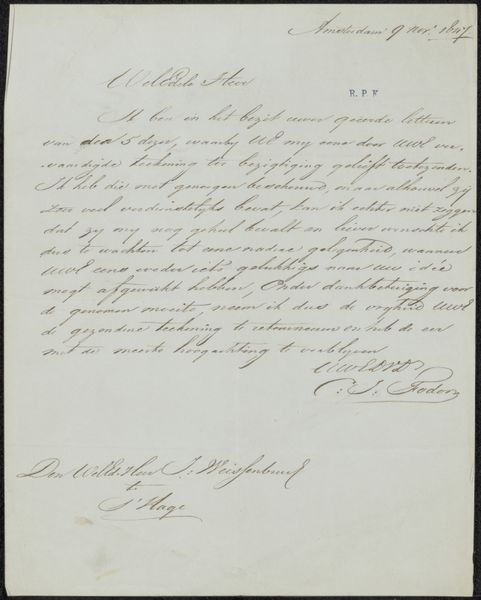

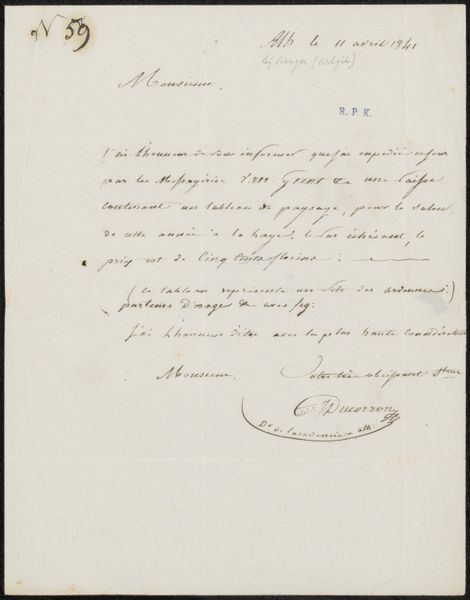

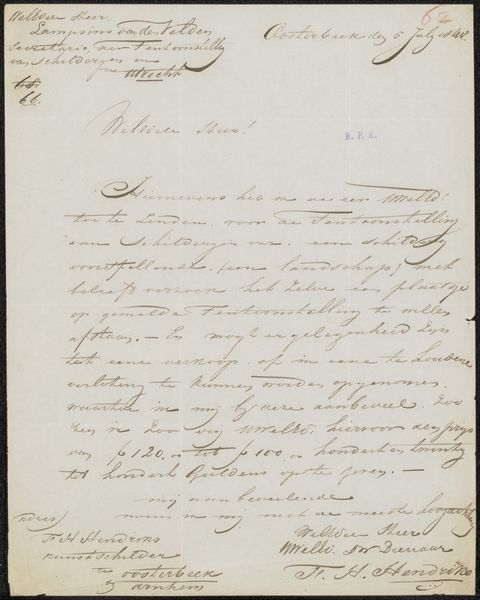

Curator: This drawing, titled "Brief aan anoniem," which translates to "Letter to Anonymous," is attributed to Augustinus Jacobus Bernardus Wouters and thought to be from 1866. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What is your first take on this work? Editor: My immediate impression is one of fragility and obscured meaning. The ink on paper appears delicate, and large section seems to have been torn away from it, creating gaps in the narrative. It evokes a sense of mystery and raises many questions about authorship, intention, and readership. Curator: Right. Considering this drawing, executed with ink on paper, allows us to ponder on literacy and communication. During the Dutch Golden Age literacy was growing, enabling greater participation in public life and economy through skills like writing and bookkeeping. But it was also gendered. A work like this prompts questions of accessibility and social standing: whose voice was amplified and whose remained unheard? What are your thoughts on the intersectional readings one might have? Editor: The context of anonymity itself is powerful. Why the need to address someone without revealing their name or for the recipient of this letter to conceal their identity? It certainly speaks to broader political currents. Anonymity offers a shield against authority, particularly crucial in spaces of political or social unrest. Given Wouters' likely position as a white male in 19th century, his choice is itself an assertion of the power he wielded over those for whom anonymity was often involuntary. Curator: And we should recognize the craft in his application of language. The materials here—paper and ink—aren't merely tools but embodiments of an epistolary social ritual, demanding a specific writing process. I find myself speculating about the labor involved in creating this manuscript. The act of writing itself, shaping letters by hand, gives texture. How would such efforts of production in 1866 translate into current economic or gendered power relations, I wonder. Editor: Yes, and it invites us to reimagine modes of communication outside official spheres. It may be viewed as a response to censorship and persecution. Its resistance stems from embracing anonymity not as a mark of shame, but a mark of protection. Curator: It seems the core lies in decoding its coded communication to recover repressed perspectives on the past and maybe use them to transform our social existence today. Editor: Ultimately, it’s that invitation—to step into the gaps and imagine the untold story that makes “Letter to Anonymous” so affecting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.