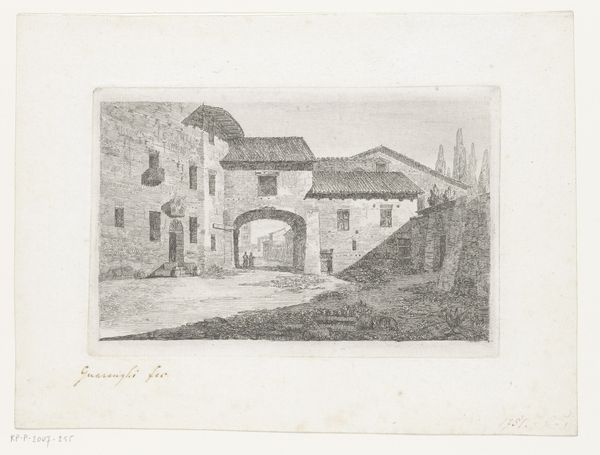

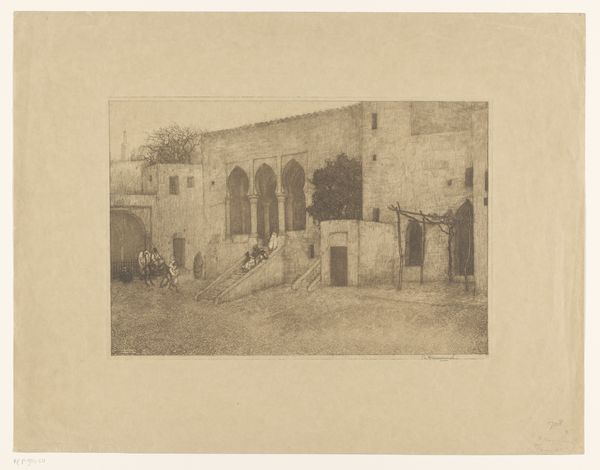

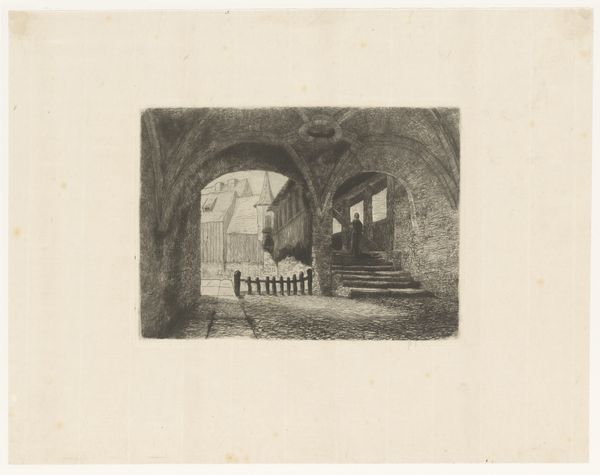

print, etching

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 223 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today we are examining "Gezicht op een binnenplaats", or "View of a Courtyard," an 1874 etching by Maria van Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. It’s rendered in ink on paper, offering a glimpse into a past architectural space. What is your initial read? Editor: It’s intensely textured! You immediately notice how the variations in tone—from light grey to nearly black—build a sense of the surfaces of walls and a deep space with heavy shading. The density of line suggests intense manual labor. Curator: Indeed. The process of etching is critical here. Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a Countess herself, would have had access to training and equipment not easily available. Think about her social status allowing her entry into the typically male dominated world of printmaking. How does that social element change your viewing? Editor: Absolutely, we are seeing the politicization of what may otherwise seem to be a quotidian, almost banal subject. Looking at her technical facility through that lens, I start thinking about the academy’s influence; the consumption and collecting practices around etching, and its connection to wealth. Curator: And the image itself is rife with class. Architectural elements are emphasized; not nature, not labor in the fields. What can that focus reveal to us about 19th-century patronage, particularly within royal circles? What do you see? Editor: The focus on this architecture tells a particular kind of historical story, too. It implicitly speaks to a desire for control, or possession, that these massive stone structures would suggest—also, there's a public element because of where this architecture has been made. It tells a visual narrative reinforcing social hierarchies for popular consumption. Curator: Considering her as Countess of Flanders provides valuable insight into the intended audiences for her work. While we have to assume most people couldn't afford art like this piece, prints still afforded wider dissemination. We are really talking about art as a cultural and political agent. Editor: A fascinating way to frame it—Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen using her privilege to create artwork not divorced from those very conditions of production, but inextricably intertwined. It prompts you to interrogate your position, too, as a viewer and consumer of historical works like these. Curator: Yes, and remembering her access to etching tools is critical to understanding the historical role of women artists within systems of art and production. Editor: Precisely, and examining “View of a Courtyard” gives us a space to examine not just what we see, but how we come to see.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.