drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

portrait reference

#

italy

#

engraving

Dimensions: 383 × 258 mm (image); 430 × 301 mm (plate); 540 × 412 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

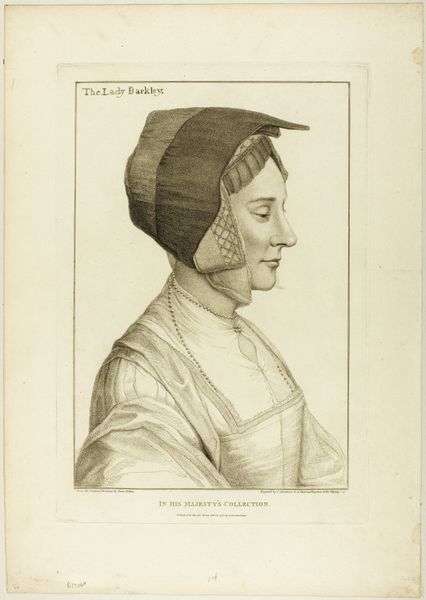

Curator: Take a moment to observe this artwork, "Portrait of a Woman", a print and drawing from around 1799 by Francesco Bartolozzi. What is your initial reaction? Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its serenity. The delicate lines and the muted tones evoke a quiet, almost contemplative mood. It has a classic elegance in its composition and delicate rendering of light. Curator: Indeed. Let’s consider this from a materialist perspective. This isn’t just an image, but an object created through specific processes and materials. Bartolozzi employed engraving, a technique that involves carefully cutting lines into a metal plate, and the result is a multiple reproducible image on paper. Consider the labour involved and the social context surrounding printmaking at this time—a moment of great changes that challenged the very way images were consumed. Editor: I find myself captivated by the way he utilizes line to define the form. Notice how he sculpts her face with these fine marks, almost hatching, giving a remarkable three-dimensionality to her features despite the monochrome medium. The tonal range achieves a sense of volume that captures her soft but elegant disposition, I am thinking of semiotics of beauty standards, which may dictate our perceptions about the individual in the engraving. Curator: Right. Moreover, such prints were produced for consumption. Think of how images were becoming democratized, not just the domain of the wealthy elite. A print like this could circulate widely, carrying messages about status, fashion, and societal ideals far beyond the walls of a noble's home. Her very presentation speaks to social norms concerning what was considered proper feminine presentation. Editor: And the head covering creates a rigid framing around her soft and humanized features, such as her slight underbite. This adds a symbolic weight to the image – perhaps indicating her status and that period’s representation of womanhood? Curator: Exactly, what might the material conditions of art production during the late 18th century tell us about consumption of visual representation. These engravings acted as cultural artifacts, encoding complex systems of representation concerning gender, power, and status within that period. Editor: This close look reminds me to consider that while analyzing artwork and dissecting its artistic intention can greatly help contextualize historical moments in society, there’s value in recognizing the original human response of the aesthetic experience. Curator: And perhaps analyzing it this way helps uncover more nuance concerning the lives and production of not just the artist but those who bought, sold, and circulated artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.