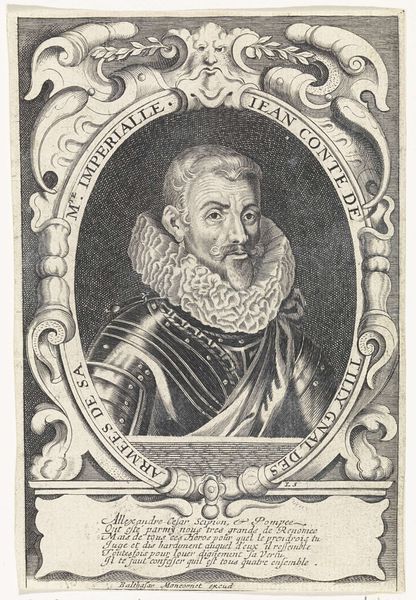

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 284 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portrait of Nicolaus Trobolaeus", an engraving made sometime between 1618 and 1630. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum, and we believe it was created by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. Editor: Oh, it's intricate! And busy! My eye just wants to bounce around the page, trying to figure out what I should be looking at first. The ruff definitely catches the light! It's also somehow imposing even though it's an engraving and a relatively small piece I imagine. Curator: That constant level of detail is a characteristic of baroque prints. Consider how the engraver meticulously cut into the metal plate to produce the crisp, detailed lines. Each line represents a deliberate decision, reflecting the artist's labour and skill. This contrasts to painting where materials are layered—engraving requires carving away at material. Editor: And that materiality speaks to power, doesn't it? This wasn't just sketched in charcoal; it's been etched with considerable time, and with skill—a collaboration, perhaps, with the sitter to showcase their significance. I find myself looking past Nicolaus to the figures and ornamentation. All these classical figures draped around this gent…a kind of reverence constructed with allegories, not only portraying him, but elevating him, as the latin verse below also clearly suggests. Curator: It's a carefully constructed image. The ornamentation, the figures of justice and possibly divine inspiration, create a symbolic frame that both literally and figuratively elevates Trobolaeus. And it is the craft of its making, that very etching itself, which lends it the ability to suggest the qualities which, at the time, only paintings were afforded, which speaks to an idea about consumption: owning his likeness would be within reach for a wider group of people! The question might then be: what kind of consumer was he envisioning himself catering to? Editor: Well, that makes me look at his expression differently. I first saw stoicism, a man of presence…but if he’s looking to wider consumption of his image, that little hint of a smile… is it calculating, do you think? A knowing glance for those in the know? This really highlights how much meaning lies in the materiality and the implied consumer in art from this era. Thank you. Curator: Indeed! Understanding the printmaking process deepens our understanding not just of the artwork itself, but of the period, too, I think. It changes how we experience these things, and how alive they seem.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.