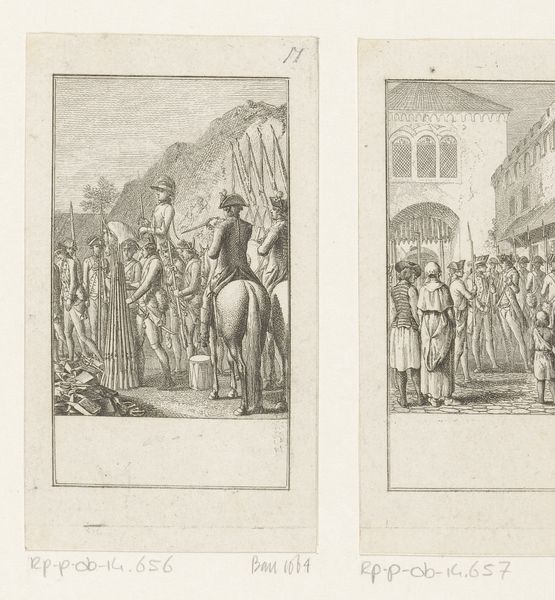

Joachim en Albrecht lopen met rector Wimpina voor aan de processie 1789

0:00

0:00

danielnikolauschodowiecki

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 76 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

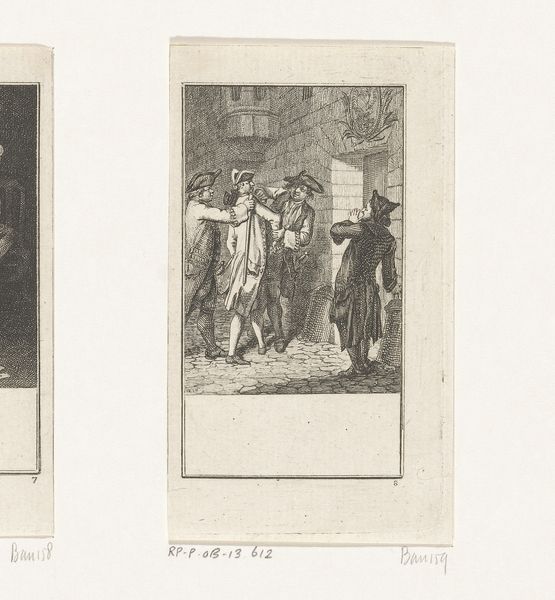

Curator: Let’s take a look at Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki’s 1789 engraving, "Joachim en Albrecht lopen met rector Wimpina voor aan de processie," currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your initial impression? Editor: Stark. It evokes a distinct sense of 18th-century Berlin, with its almost severe clarity and regimented figures. The monochromatic palette feels historically accurate, giving the scene an austere feel. Curator: Chodowiecki was known for his precise engraving technique, emphasizing the lines to define form. He worked during a period of growing interest in realism and moralizing narrative, which significantly shaped the market for printed images, impacting distribution and consumption of art. Note the careful depiction of fabrics and the subtle shadowing he achieves, presumably enabled by developments in printing at the time. Editor: Absolutely. It's interesting to consider the social context of processions like these. Who was allowed to participate, who was excluded? These performances of power solidify the existing hierarchies, enforcing dominant ideologies through symbolic display. Also the gaze of the spectators, look how closely it resemble what is on the process? Do you think that Chodowiecki was criticising those dynamics by any means? Curator: The uniformity of the lines, indicative of the printing processes and skills needed to make them, reflects a burgeoning era of mass production that affected everything from texts to images. Did such new forms influence access to this kind of subject matter? Chodowiecki found fame crafting illustrations for popular literature, his graphic skill and industrial savvy enabled social commentary through readily accessible, and relatively affordable images, even though most prints of the time served decorative or didactic purposes. Editor: I think so, and while the image seems ostensibly neutral, we cannot forget that this visual record privileges certain narratives over others. To the spectator, the solemnity could speak of state endorsement; but for others, exclusion. What kind of social capital did partaking in processions afford them and those who were intentionally or unintentionally overlooked by this particular system? Curator: His use of print, particularly engravings, made art more accessible, moving it beyond elite circles, with some unintended consequences, such as reproductions and imitations by those that were less skilled with the materials and thus devaluing the artistic process as a whole. What should remain in sight are not just his skills but also the era’s dynamic shift in artistic distribution enabled by evolving methods of production and an expanding marketplace. Editor: Thinking about it from this vantage point underscores how every artifact carries layers of sociopolitical coding embedded within. It reminds me of current dialogues on power, access, and how artistic narratives reflect and reinforce the frameworks defining inclusion and recognition.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.