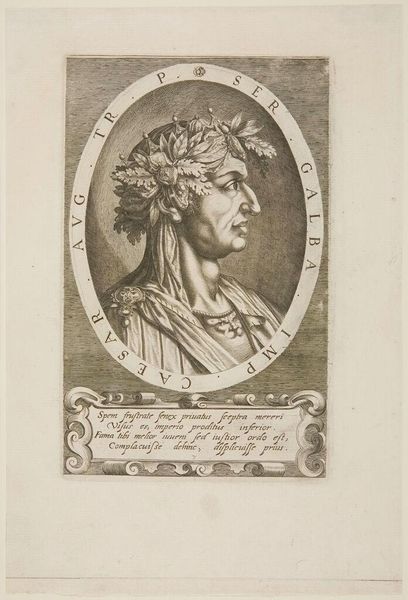

Plate 7: Sergius Galba in profile to the right, from "The Twelve Caesars" 1610 - 1640

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

mannerism

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 20 1/4 × 14 9/16 in. (51.4 × 37 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

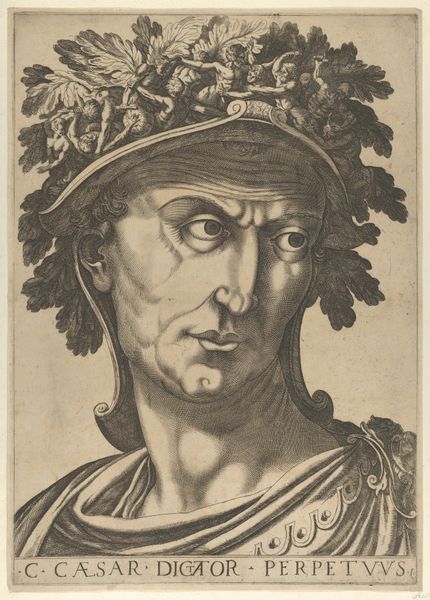

Curator: Up next, we have an engraving dating from the early 17th century, sometime between 1610 and 1640, titled "Plate 7: Sergius Galba in profile to the right, from 'The Twelve Caesars.'" It's currently part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection. Editor: Oof, the gaze could cut glass, couldn’t it? Makes you wonder what secrets those eyes are hiding, or maybe what orders he's about to bark. It has a real severity, don't you think? Curator: Absolutely. And that severity is exactly what artists of the period, influenced by Mannerism, were aiming for. The subject is Galba, one of the less… successful Roman emperors, who ruled for a tumultuous seven months. He was chosen after Nero's death, promising reform, but failed to deliver and was assassinated. Editor: Seven months! Talk about a tough gig. It seems as though the artist really honed in on that feeling of him carrying the weight of the world – and probably a fair few enemies – on his shoulders. Curator: Indeed. Prints like these, part of larger series portraying Roman emperors, served multiple functions. They were a way to disseminate knowledge of history and classical antiquity, but also they subtly reinforced contemporary power structures by drawing parallels—or creating contrasts—with rulers of the time. Note the laurel wreath, a powerful symbol co-opted across centuries to convey authority and victory. Editor: Victory feels like a long shot looking at him now. The laurel looks more like a thorny crown here, each leaf edged in worry. You know, there’s almost a modern quality to the line work in his face – those etching marks really bring out a world of anxiety etched in his skin, or transferred there somehow. Curator: The use of engraving was extremely common in reproducing images. Engravings were crucial to distributing images across Europe to shape perception of historical and political figures like Galba. Editor: Makes you wonder about the engraver’s own biases or what political spin they were being asked to put on old Galba. Was this flattery, a warning, or just a history lesson? Maybe it’s all three, tangled up together. Thanks for that look at this, you helped tease out something that otherwise might have been lost in the fine lines of the work. Curator: My pleasure! The social context around the distribution and understanding of images from the past holds lessons and ideas for modern society today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.