albumen-print, public-art, photography, albumen-print, architecture

#

albumen-print

#

excavation photography

#

public art

#

surveyor photography

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

public-art

#

historic architecture

#

photography

#

city scape

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

street photography

#

history-painting

#

public art photography

#

albumen-print

#

architecture

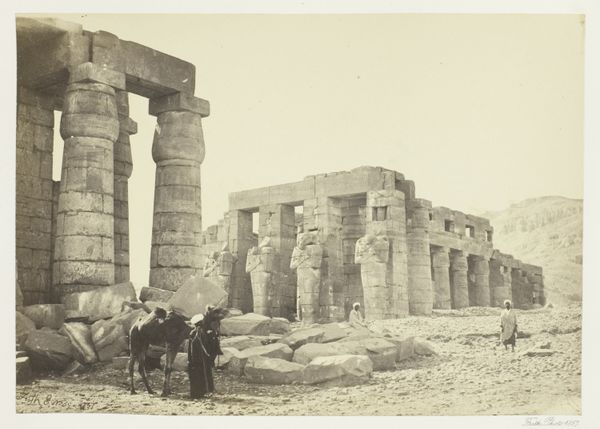

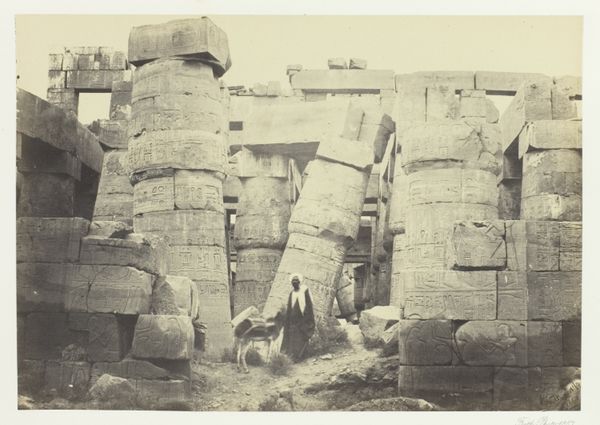

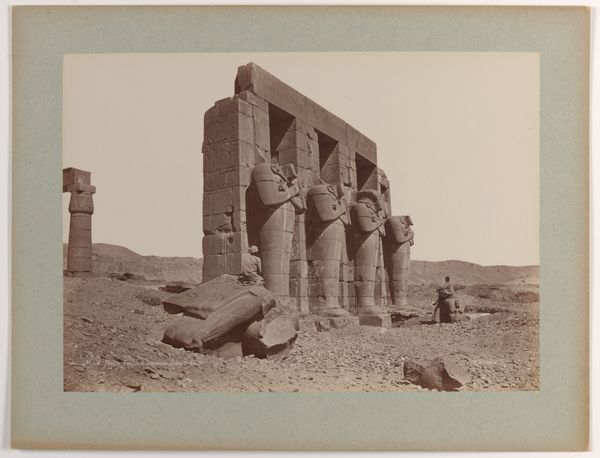

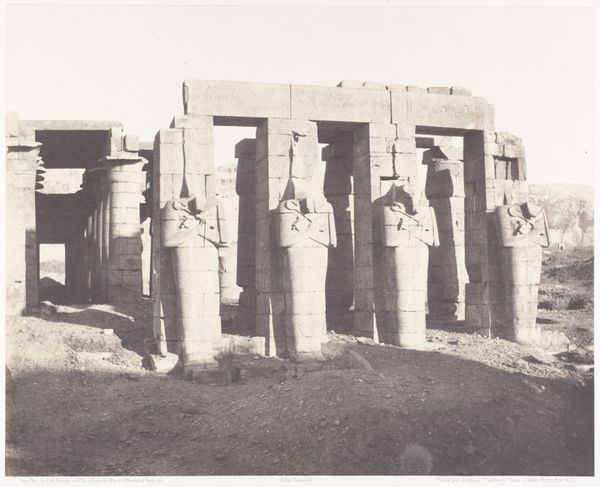

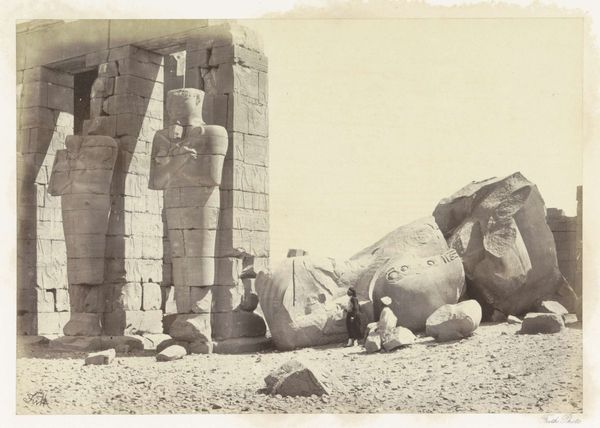

Dimensions: 8 5/16 x 10 5/16 in. (21.11 x 26.19 cm) (image)11 x 14 in. (27.94 x 35.56 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

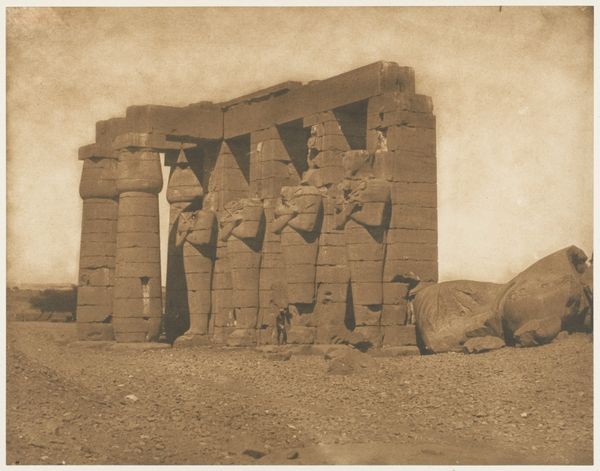

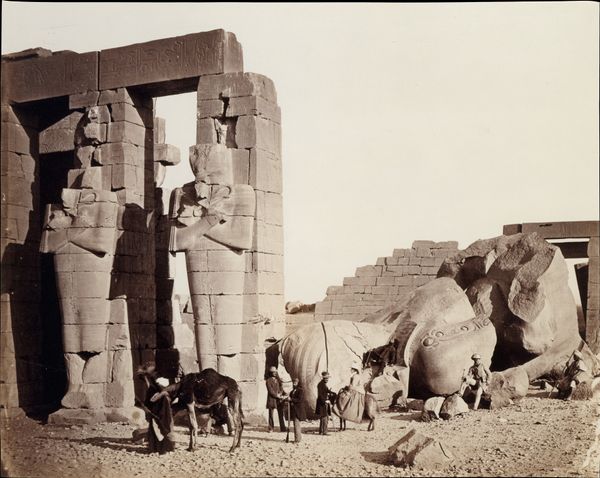

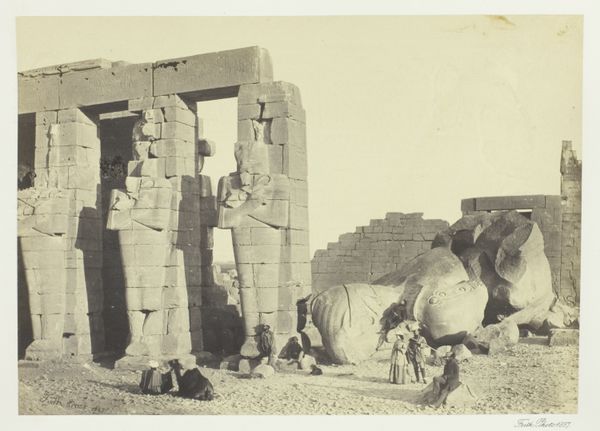

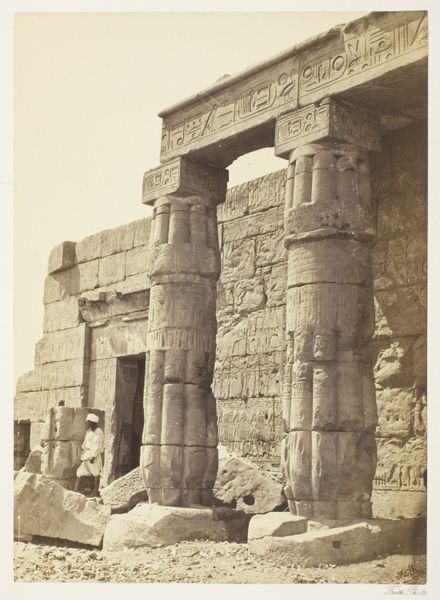

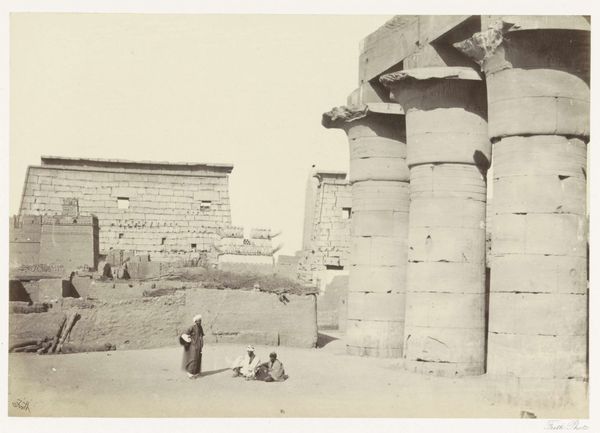

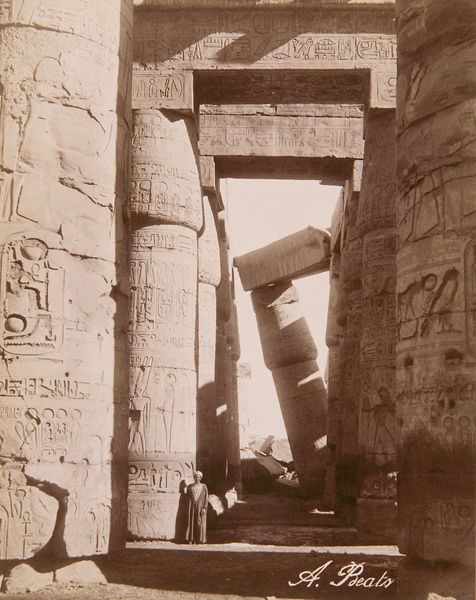

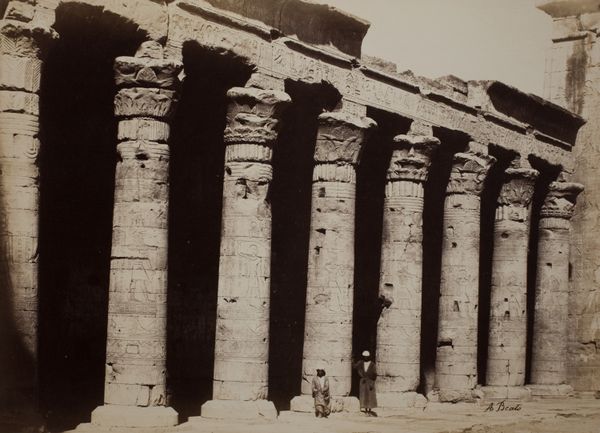

Curator: Looking at Antonio Beato’s albumen print from the 19th century titled "Pylon and Colossi of Ramesses II", my first reaction is one of profound melancholy. The ruins evoke such a palpable sense of lost grandeur. Editor: Absolutely. The scale is overwhelming, even in this image. The colossi, though damaged, still stand as testaments to power and longevity. It makes me think about the fleeting nature of empires and the stories these stones could tell about Ramesses II's reign. What cultural echoes do you hear in these colossal ruins? Curator: For me, it is about visual legacy. Beato’s lens captures not just the physical remnants, but also the enduring symbolic weight. The pylon itself, with its hieroglyphs, acts as a gateway, almost a symbolic membrane between worlds, carrying the stories across millennia. The fragmented state adds layers; it reflects the weathering by time, but it does not negate its powerful presence. Editor: Yes, there’s also a complicated layer in viewing this through Beato’s colonial gaze. As a European photographer, he frames these ancient structures for a Western audience, subtly influencing perceptions of Egyptian civilization. I find myself questioning his intentions, whether his gaze celebrates or subtly others this civilization. Curator: That’s a vital consideration. The figures in the foreground, seemingly local people, serve as scale markers but also invite viewers into the scene. The question is how their presence influences the way Westerners would understand ancient Egypt and its relation to the contemporaneous population. It is all layered. Editor: Exactly. How does viewing through the colonial lens change how we approach the symbolism and intended cultural meaning, and whose narrative is prioritized. The composition even implies that these individuals exist merely to emphasize the size and scope, to provide evidence for European fascination. It raises questions about appropriation and control. Curator: An important point. Yet, I can’t help but also see it as a powerful intersection of artistry meeting historical preservation—however flawed by its context. In a world increasingly devoid of shared symbolic systems, seeing the vestiges of one as potent as ancient Egypt has enormous appeal. Editor: It is appealing and yet it also necessitates reflection, wouldn't you say? Ultimately, what moves me here is how an image meant to document instead invites me to engage in dialogue between art history and modern day theories on cultural meaning. Curator: Agreed. And, ultimately, that ongoing dialogue ensures that its powerful symbolic echo does not become a cultural monolith, but remains a potent space for discourse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.