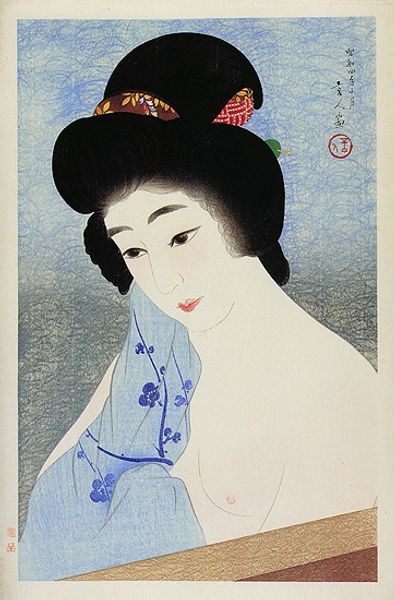

Copyright: Torii Kotondo,Fair Use

Editor: This is Torii Kotondo’s “In a Long Undergarment,” a woodblock print from 1929. The first thing that strikes me is the pattern of the kimono, all these swirling clouds. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a layered narrative, one that engages with the complex position of women in Japanese society during the Taisho and early Showa periods. Ukiyo-e prints like this were often read as straightforward depictions of female beauty, but Kotondo offers something more nuanced. Editor: How so? Curator: Consider the title. "In a Long Undergarment" isn’t exactly glamorous. It draws attention to the woman’s private life, a space historically governed by patriarchal norms. The intricate kimono design, while beautiful, might also be seen as a kind of luxurious constraint, reflecting the limited social roles available to women of her class. Editor: So the beauty is deceptive? Curator: Perhaps. Or perhaps it's a demonstration of agency. The woman isn't simply a passive object; her gaze is averted, contemplative. She occupies her own space, even within these constraints. It also engages with the rise of "modern women," known as "modan garu", pushing for more freedom. Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. It makes me wonder about the artist's intent and the message he was trying to convey about the role of women in this period. Curator: Exactly! And think about how the "floating world" aesthetic intersects with feminist and social issues, reflecting evolving social and political contexts of that time. Editor: This has really broadened my perspective on ukiyo-e. It's not just about surface-level beauty; there are complex stories embedded within these images. Curator: Indeed. It invites a re-evaluation of traditional Japanese art through the lens of gender and identity, providing space for dialogue between the artwork, society, and self.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.