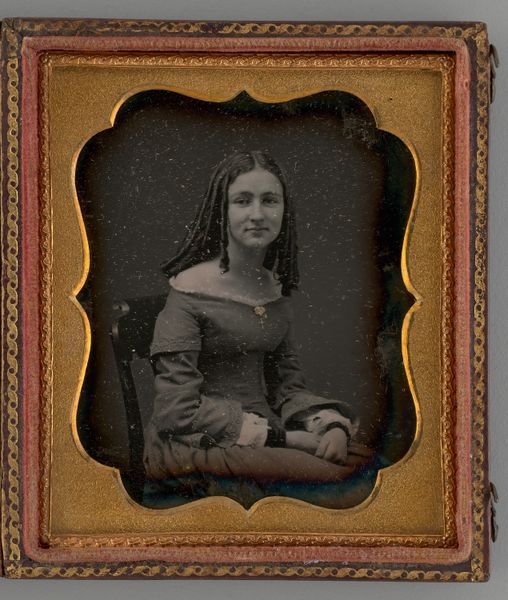

Portret van Margaretha Jacoba Wiggers van Kerchem, echtgenote van Geldolph Adriaan de Lange c. 1850

0:00

0:00

dhracine

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

19th century

Dimensions: height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a portrait from around 1850, "Portret van Margaretha Jacoba Wiggers van Kerchem, echtgenote van Geldolph Adriaan de Lange." It’s a photograph, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. The woman depicted seems so proper and reserved. What strikes you when you look at this, from a historical perspective? Curator: It's fascinating how these early photographic portraits became potent tools for social representation. Here we see Margaretha, a wife of status, carefully adorned with jewellery. Her posture, the lighting, everything screams ‘respectability’ - a key concern of the rising bourgeoisie in the 19th century. Editor: So, the portrait is less about the individual and more about social signalling? Curator: Precisely! Think about the institutions and economic conditions that birthed photography. These portraits were expensive, a visual marker of success. They were displayed in homes, shaping social perceptions. Notice how the composition deliberately avoids any hints of informality? What message do you think that sends? Editor: That it was about adhering to societal norms? Perhaps solidifying her place and her family’s within a certain social standing? Curator: Exactly. The power of early photography lay not just in capturing likeness but in curating a very specific, socially approved image for public consumption. Now imagine what that did to people who didn't fit this particular mold! Editor: That's an angle I hadn't considered. It really emphasizes the exclusivity around these images. Thanks, it’s helped me think about these images and social roles more critically. Curator: My pleasure. Remembering art's impact on the structures and people surrounding its conception is very useful when viewing such art!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.