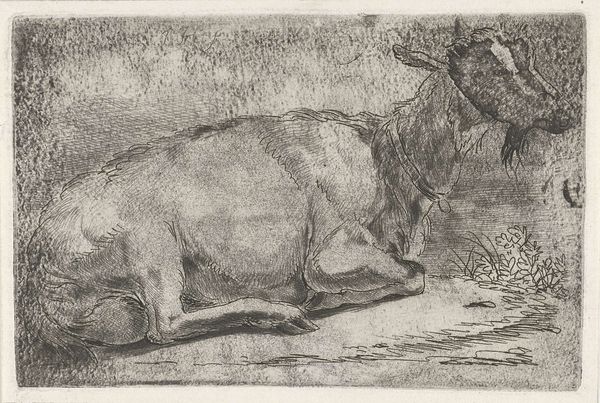

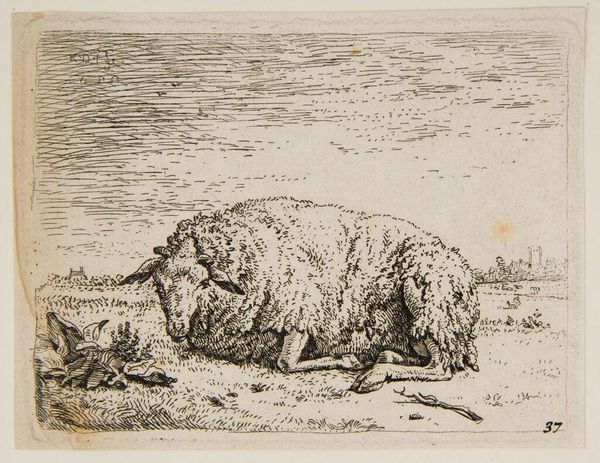

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

animal

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 93 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re looking at "Liggend everzwijn," or "Reclining Wild Boar," an etching and print by Jacobus Cornelis Gaal, created around 1850. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me as melancholy. There's a certain stillness, a vulnerability to this animal presented in such a quotidian way. The stark black lines against the pale paper create a rather somber mood, wouldn’t you say? Curator: It's definitely a departure from heroic portrayals of animals common in earlier art. Gaal’s interest, characteristic of the burgeoning Realist movement, seems to lie in depicting this wild boar unidealized, perhaps even exhausted. We see it not as a symbol, but as an animal caught in a specific moment in its habitat. Editor: And what is the socio-political context here? Is Gaal making some kind of statement on class, rural life, or perhaps the changing landscape of the Netherlands at this time? Curator: The mid-19th century in the Netherlands was a period of agricultural change and growing urbanization. Works such as this could be interpreted as a reflection on the impact of human activity on the natural world, perhaps highlighting a tension between pastoral life and modernization. Furthermore, hunting was heavily regulated, intertwined with social class. The representation of wild animals also holds implications in art history with regard to genre paintings. Editor: I agree. It's interesting to consider how something as seemingly straightforward as an animal study participates in those larger cultural discourses. And how does the work reflect the power dynamics between humanity and nature? The fence almost seems to imply capture, imposing a boundary in the boar's natural setting. Curator: That is a sharp reading of this, indeed, to me, it suggests our attempt to tame the wild as human culture expands. By stripping away grandeur, Gaal brings forward these subtle yet crucial statements, leaving lasting and intricate dialogues between artwork and beholder. Editor: A reminder that even in simple realism, social commentaries are embedded within. Curator: Indeed, offering fertile ground for discussion on animal agency and cultural control in 19th century art and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.