drawing, print

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

nude

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 8 3/4 × 6 3/8 in. (22.2 × 16.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

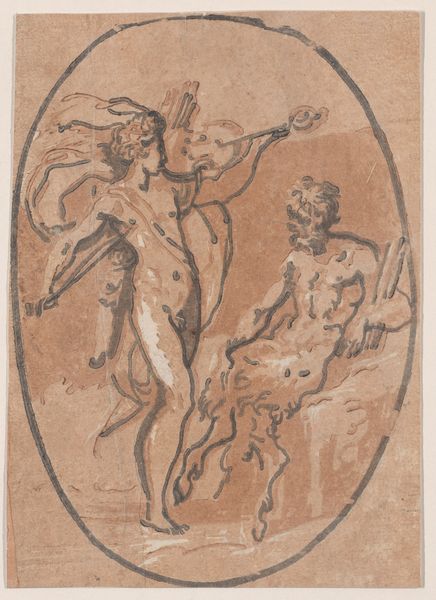

Curator: This print, likely a drawing reproduced as a print, is titled "Diana and Endymion," and was created sometime between 1650 and 1700 by Giuseppe Diamantini. It's currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fine, etched lines give it a compelling energy. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It strikes me as quite theatrical, almost stage-like, with the figures arranged as if posing for an audience. The hazy execution and dense layers feel dreamlike, yet I wonder about the materiality. How were these impressions produced and replicated? Curator: Well, consider the baroque period it comes from—everything was about drama! But I am intrigued by the power dynamics displayed in the print. The story of Diana, a powerful goddess, descending upon the mortal, Endymion. Think about the inherent privilege and exploitation woven into this narrative of immortal desire. Editor: Indeed. We can’t ignore the colonial gaze embedded in this European artwork depicting a very romanticized view of desire and power. Was this drawing made as a preparatory sketch or a demonstration piece, perhaps? Was Diamantini experimenting with reproductive techniques and creating an inexpensive means of distribution and exchange? Curator: Certainly, dissemination was a factor, giving rise to questions of taste and patronage. In the story itself, the theme of agency is fascinating when viewed through a feminist lens. Diana's power is unquestioned, yet Endymion is passive, a figure merely acted upon. The dynamic hints at wider discussions regarding women's rights. Editor: I agree. Consider the paper it's printed on—its social life as a commodity. The paper's provenance can tell its own story, charting historical routes of trade and global exchange. Who exactly was consuming these prints, and what role did they play in creating, maintaining, and challenging existing systems of class and gender hierarchies? Curator: Those are compelling questions that prompt us to see the drawing less as a static object and more as a conduit for cultural exchange, social critique, and artistic dialogue. Thank you! Editor: Thank you! A great example of how close observation reveals production details that broaden and deepen our awareness of the artwork's place in the material world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.